Themes > Current Issues

22.04.2004

What the Rising Rupee Signals

C.P.

Chandrasekhar

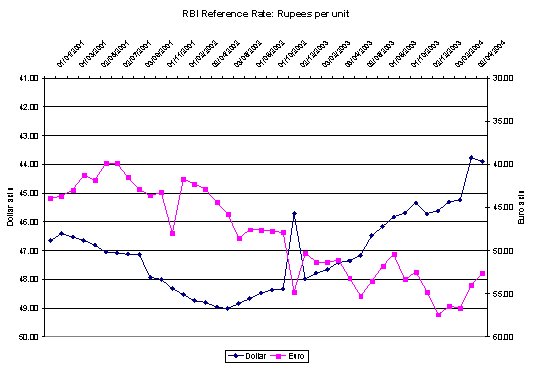

The

Indian rupee is on the rise. While its appreciation vis-à-vis

the dollar began in June 2002, when it had touched a low of more than

Rs. 49 to the dollar, it has been rising vis-à-vis the Euro as

well over the last four months. During these periods of ascent, it has

appreciated by close to 12 per cent vis-à-vis the dollar in 22

months and by a significant 9 per cent vis-à-vis the Euro in

a short period of 4 months. Not surprisingly, exporters have begun to

get restive; since a loss of 10 per cent in the rupee price of their

exports can shave off margins on past fixed-price dollar/euro contracts

and make it difficult to win new orders.

The rise of the rupee is partly attributable to the depreciation of

the other currencies, especially the dollar against those of its competitors.

That this was true for some time is reflected in the fact that while

the rupee was appreciating against the dollar for close to two years,

it was depreciating vis-à-vis the euro for much of this period.

This is, however, only small cause for comfort, since most export contracts

are denominated in dollar terms. Moreover, in recent months, as noted

above, the rupee has been appreciating against the euro as well.

Two factors have influenced this rise of the rupee vis-à-vis

various currencies. First, the excess supply of foreign currency, relative

to demand for current and capital account transactions from resident

individuals, agencies and institutions, other than the Reserve Bank

of India. Second, the willingness of the central bank to buy foreign

currencies to add to its reserves and, thereby, increase the demand

for these currencies in the market. The role of market demand and supply

in determining exchange rates and the consequent shift to market mediated

intervention by the central bank has been the natural outcome of the

adoption of a liberalised exchange rate system over the 1990s.

The pressure on the rupee leading to its appreciation, which is affecting

export competitiveness adversely, arises because India, which has recorded

a current account surplus since financial year 2001-02, has encouraged

and attracted large inflows on its capital account. India's current

account surplus, we must note, is not a reflection of its strong trade

performance. Rather, it is because, net inflows under what is called

the ''invisibles'' head of the current account of the balance of payments

has been more than adequate to finance a large and recently rising merchandise

trade deficit.

The principal sources of current account inflows have been buoyant remittance

flows and inflows under the ''software services'' head. That is, transfers

made by Indian workers abroad, either on short or long-term contracts,

have helped overcome the adverse balance of payments consequences of

India's lack of competitiveness reflected in a large trade deficit.

Inflows on account of software services rose from $5.75 billion in 2000-01

to $6.88 billion in 2001-02, $8.86 billion in 2002-03 and $9.09 billion

over the first nine months of 2003-04, while private transfers (mainly

remittances) touched $14.81 billion in 2002-03 and $14.49 billion during

April-December 2003, after having fallen from $12.8 billion to $12.13

billion between 2000-01 and 2001-02. In an intensification of this trend,

during the first nine months of the recently ended financial year 2003-04,

net inflows on account of invisibles stood at $18.22 billion, well above

the $15 billion deficit on the trade account.

Even while India's current account was relatively healthy on account

of the foreign exchange largesse of Indian workers abroad, the country's

liberalised capital markets have attracted large inflows of capital

amounting to a net sum of $10.57 billion in 2001-02, $12.11 billion

in 2002-03 and a massive $17.31 billion during the first nine months

of 2003-04. Expectations are that, because of the huge portfolio capital

inflows during the last three months of 2003-04 encouraged by the government's

privatisation drive, net capital account inflows during 2003-04 will

be in excess of $20 billion.

There are two issues that arise in this context. The first relates to

the nature of the capital inflows during these years. The second to

the implications of these inflows for the value of the rupee under India's

liberalised exchange rate management system. Three kinds of inflows

have dominated the capital account. An early and important source of

inflow during the years of financial liberalisation has been in the

form of NRI deposits in lucrative, repatriable foreign currency accounts.

On a net basis, such inflows accounted for $2.32 billion, $2.75 billion,

$2.98 billion and $3.5 billion respectively in 2000-01, 2000-02, 2002-03

and April-December 2003 respectively. They reflect the attempt by richer

non-residents to exploit arbitrage opportunities offered by the higher

(relative to international rates) interest rates on repatriable, non-resident,

foreign exchange accounts, to earn relatively easy surpluses.

A second important source of capital inflows has been portfolio capital

flows, reflecting investments by foreign bodies, especially foreign

institutional investors, in India's stock and debt markets, encouraged

more recently by the disinvestment of shares in profitable public sector

undertakings. On a net basis, such inflows had fallen from $2.59 billion

in 2000-01 to $1.95 billion in 2001-02 and just $944 million in 2002-03,

but rose sharply to $7.62 billion in the first nine months of 2003-04.

As compared with this, net foreign direct investment has been relatively

stable, at $3.27 billion in 2000-01, $4.74 billion in 2001-02, $3.61

billion in 2002-03 and $2.51 billion during April-December 2003.

The third important source of capital inflows was a financial liberalisation-induced

increase in the net liabilities of commercial banks (other than in the

form of NRI deposits), which rose from a negative $1.43 billion in 2000-01

to $2.63 billion in 2001-02, $5.15 billion in 2002-03 and $2.56 billion

during April-December 2003. This is possibly explained by the expansion

of the operations of international banks in the country.

In sum, capital inflows that create new capacities either in manufacturing

or in the infrastructural sectors have been limited. Much of the capital

inflow has consisted of financial investments that expect to earn higher

annual returns than available in international markets or obtain windfall

gains from the appreciation of the value of such investments, as has

recently been witnessed in India's stock markets.

Given the determination of the exchange rate of the rupee by supply

and demand conditions in the market, this large inflow of foreign capital

in the context of a current account surplus was bound to exert an upward

pressure on the rupee. When inflows contribute to an appreciation of

the rupee, foreign investors also gain from the larger pay off in foreign

currency that any given return in rupees involves. This tends to increase

the volume of inflows. The real losers are exporters, on the one hand,

who find that the foreign exchange prices of their products are rising,

eroding their competitiveness, and domestic producers, on the other,

who find that the prices of competing imports are falling or rising

less that their own costs of production.

However, this potential loss of competitiveness on account of surging

capital inflows was stalled for long by the intervention of the central

bank. By purchasing foreign currency from the domestic market and adding

it to its reserves, the Reserve Bank of India increased the demand for

foreign currency and dampened the rise of the rupee. The foreign exchange

assets of the central bank rose sharply, from $42.3 billion at the end

of March 2001 to 54.1 billion at the end of March 2002, $75.4 billion

at the end of March 2003 and $113 billion at the end of March 2004.

This implies that even after discounting for the increase in reserves

resulting from the appreciation of the dollar value of the RBI's Sterling,

Yen and Euro reserves, the foreign exchange assets of the central bank

were rising by around $980 million a month in 2001-02, $1.4 billion

a month in 2002-03 and $2.5 billion a month during 2003-04. Further,

because of inflows on account of the sale of equity in companies such

as ONGC and ICICI bank, foreign exchange assets rose to $116.1 billion

during the first nine days of 2004, or by a whopping $3.1 billion.

These magnitudes have two implications. First, they suggest that the

RBI has had to sustain a rapidly rising rate of acquisition of foreign

currency in order to dampen the rise of the rupee and preserve export

competitiveness. Second, that despite this sharp rise in the foreign

exchange assets of the central bank the task of managing the rupee's

exchange rate is proving increasingly difficult leading to a rise in

its value.

The task of managing the rupee is daunting because, when the central

bank increases its foreign currency assets to hold down the value of

the local currency, there would be a corresponding matching increase

in the liabilities of the central bank, amounting to the rupee resources

it releases within the domestic economy to acquire the foreign exchange

assets. If forced to continuously acquire such assets, the resulting

release of rupee resources would lead to a sharp increase in money supply,

undermining the monetary policy objectives of the central bank. Since

financial liberalisation implies abjuring direct measures of intervention

to curb credit and money supply increases, the central bank has sought

to neutralise the effects of reserve accumulation on its asset position,

by divesting itself of domestic securities through sale of government

securities it holds.

This process of ''sterilising'' the effects of foreign capital inflows

through sale of government securities has, however, proceeded too far.

The volume of rupee securities (including treasury bills) held by the

RBI has fallen from Rs. 150,000 crore at the end of March 2001 to Rs.140,000

crore at the end of March 2002 and Rs. 115,000 crore at the end of March

2003, before collapsing to less than Rs.30,000 crore by the end of March

2004. The possibility of using its stock of government securities to

sterilise the effects of capital flows on money supply has almost been

exhausted. Foreign investors have made a complete mockery of the much-trumpeted

''autonomy'' of the central bank won by curbing the government's borrowing

from the RBI.

In the current context, there are only two options available with the

government for preventing a capital flow-induced appreciation of the

rupee that could not just reduce India's exports but also deindustrialise

the economy and devastate agriculture by cheapening imports that are

now free. The first is to resort to measures that could reduce the volume

of inflows. A feeble effort in that direction has been the gradual reduction

in the differential between interest rates paid on non-resident foreign

exchange deposits and those prevailing in the international market,

as reflected by the LIBOR. The ceiling on interest on non-resident external

deposits had earlier been linked to the LIBOR and set at 0.25 per cent

above it. Now the ceiling has been set at the LIBOR itself.

But NRI inflows during April-December 2003-04 only accounted for around

a fifth of net capital inflows into the country, and that ratio is likely

to be much smaller in the subsequent months. Managing the rupee by controlling

capital inflows requires targeting portfolio flows. That is the signal

that the rising rupee sends out. Unwilling to heed that signal, the

government has decided to encourage outflows on the current and capital

account by removing the few import controls that remain, reducing duties,

easing access to foreign exchange for current account transactions like

travel, education and health and, most important, relaxing outflows

on the capital account by permitting firms and individuals to transfer

money abroad for investment purposes.

The dangers of blowing up in this manner the foreign exchange obtained

in the form of volatile capital flows should be obvious. What is more,

it is unclear whether this would resolve the problem. The process of

liberalisation may, in the short run, make India an even more favoured

destination for foreign investors. The rupee could appreciate further.

Exports could shrink. Further liberalisation aimed at increasing foreign

exchange outflows could damage the domestic production system. All of

which could finally encourage investors to walk out on India, in the

perennial search of markets that have not yet been destabilised. That

would deliver an economic scenario that no one would want to conjure

for this country.

Table

for Chart |

Dollar |

Euro |

01/01/2001 |

46.66 |

43.95 |

01/02/2001 |

46.40 |

43.67 |

01/03/2001 |

46.53 |

42.95 |

03/04/2001 |

46.64 |

41.26 |

02/05/2001 |

46.81 |

41.82 |

01/06/2001 |

47.05 |

39.87 |

02/07/2001 |

47.07 |

39.87 |

01/08/2001 |

47.13 |

41.51 |

03/09/2001 |

47.13 |

42.87 |

01/10/2001 |

47.93 |

43.61 |

01/11/2001 |

48.00 |

43.24 |

02/12/2002 |

48.32 |

47.97 |

01/02/2002 |

48.53 |

41.68 |

01/03/2002 |

48.75 |

42.27 |

02/04/2002 |

48.80 |

42.90 |

02/05/2002 |

48.96 |

44.36 |

03/06/2002 |

49.02 |

45.72 |

01/07/2002 |

48.84 |

48.55 |

01/08/2002 |

48.67 |

47.55 |

02/09/2002 |

48.48 |

47.56 |

01/10/2002 |

48.36 |

47.76 |

01/11/2002 |

48.34 |

47.87 |

02/12/2003 |

45.71 |

54.77 |

© MACROSCAN

2004