To

those outside the government, the evidence on India's

export performance is confusing indeed. On the one

hand, the dollar value of India's aggregate exports

seems to have weathered the crisis and then staged

a smart recovery.

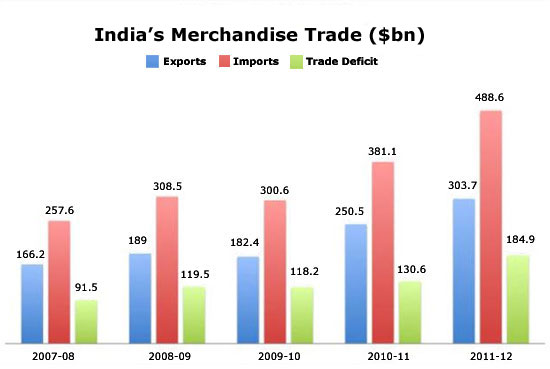

It rose from $166 billion in 2007-08, to $189 billion

in crisis year 2008-09 and fell marginally to $182

billion during 2009-10. It has since risen sharply

to $251 billion in 2010-11 and a target-exceeding

$304 billion in 2011-12.

This performance has been attributed by some to a

newfound strength in manufactured exports that could

see India escaping from its dependence on services

for growth.

Chart

1 >> (Click

to Enlarge)

However, the Ministry of Commerce, responsible for

pushing India's exports, seems pessimistic. On multiple

occasions the Secretary Commerce has cautioned against

expecting exports to continue to perform well, given

waning global demand resulting from the prolonged

crisis in Europe. While this does stand to reason,

it leaves unexplained the resilience of Indian exports

during the principal crisis years and its robust recovery

subsequently. Especially surprising would be the 21

per cent increase in exports in 2011-12.

It could be argued that the Commerce Secretary's views

have been influenced by the deceleration in export

growth during the second half of the last financial

year, when average export growth relative to the corresponding

period of the previous year was in single digits.

But even this fails to clarify. If export growth was

sluggish during the second half of the year, then

simple arithmetic would suggest that performance during

the first half must have been so remarkable that the

average for the year as a whole exceeded 20 per cent.

Thus, if we take the April-November 2011 period for

example, export growth was paced at 33 per cent. What

explains that buoyancy, given the fact that the world

in general and Europe in particular were in crisis

during the period in question? Thus the reasons why

export were initially buoyant in 2011-12 and then

sluggish and are expected to remain so in the coming

months are clearly the Commerce Ministry's best-kept

secrets.

There are, however, speculative explanations that

have been doing the rounds. One is that the official

export figures are substantially inflated. Limited

sample surveys (of the top-500 listed companies by

Kotak Mahindra, for example) pointed in that direction.

This conjecture tuned out to have some substance when

in November the government reportedly admitted that

export figures for the April to November period had

been inflated to the tune of $9 billion due to problems

with the computer software that had been recently

upgraded.

However, what needs noting is that even after correcting

for this ''error'' the export growth rate for the April

to November 2011 period was at the creditable 33 per

cent mentioned earlier. And, in November, the Commerce

Secretary had projected that exports over the full

financial year would be around $280 billion as opposed

to the $300-plus billion at which it is now estimated.

This does raise the possibility that the export figures

had been and are being inflated, because of software

errors or other reasons, even after the correction.

But this is not the only speculation regarding the

strange tale of India's export boom. The other is

that exports are being over-invoiced substantially

in order to bring back to India, in the form of spurious

export receipts, money that had been illegally transferred

abroad earlier. There are a number of reasons why

those having stashed away wealth abroad would now

like to bring to it back to the country, even in forms

that are liable to be taxed. The first is the growing

international agreement, prompted by security and

not economic reasons, on the need to share more information

on the financial holdings abroad of citizens of different

countries. Taxes may be a small price to pay to avoid

possible incarceration. The second is that the returns

on investing capital of this kind in international

market may be shrinking, making it a good time to

invest in India.

And, finally, what better time to bring dollars back

to India than one in which the rupee is depreciating?

However, till such time that there is more concrete

evidence of over-invoicing of exports and circumstantial

evidence of reversal of capital flight, this explanation

for India's ostensible export success must remain

in the realm of speculation.

But to cut the discussion short, there does seem to

be reason to conclude that the buoyancy in India's

exports is possibly an exaggeration. But, since official

figures point to a significant rise in exports, the

government needs an explanation, which has been found

in the fact that the composition of India's exports

are such that it is partly insulated from the effects

of the crisis. However, this is not immediately clear

from the available figures, since commodity groups

such as engineering goods, drugs and pharmaceuticals,

leather and textiles, besides petroleum and oil products

were the high growth areas. These are not areas in

which exports would not have been affected by the

crisis.

Moreover, infrastructural constraints and market saturation

are provided as reasons why this growth cannot be

sustained in the future. But why these constraints

have become operative now or cannot be relaxed is

left unspecified.

The truth must lie somewhere else. But that again

seems to be in a file marked secret.

*

This article was originally published in The Hindu,

‘Economy Watch' (April 30, 2012)