In the Middle of a Muddle*

While

economists of repute increasingly populate India's policy-making

establishment, holding regular or advisory positions, economic policy

itself seems ever more self-contradictory. Consider, for example,

the monetary and fiscal policy recommendations being made by this

establishment as reported by the media. There is a growing consensus

within it that the Reserve Bank of India should reduce overly high

interest rates to revive growth, even while maintaining a close

watch on inflation. In this view, inflation is a threat, but not

so much as to warrant stifling growth with high interest rates.

Responding to this pressure the RBI has in its recent annual policy

statement decided to go in for a significant half-a-percentage-point

reduction in the repo rate.

Meanwhile another argument is gaining ground that fiscal policy

should play a greater role in controlling inflation. The magic remedy

for inflation being recommended by adherents to this view is a reduction

in the fiscal deficit on the government's budget. Besides being

based on the belief that a reduced fiscal deficit would automatically

rein in inflation, this recommendation is noteworthy for the specific

way in which the reduction is sought to be ensured. The government

is being urged to reduce its expenditure to curtail the deficit

by raising administered prices and user charges and cutting budgetary

subsidies. More specifically, a case is being made out for raising

the prices of petroleum products so as to reduce subsidies or transfers

to the oil marketing companies. In recent times this establishment

demand has become an orchestrated campaign. The argument from sources

in the Finance Ministry and the Planning Commission seems to be

that if you raise a set of prices that would reduce the fiscal deficit,

the overall rate of price increase would be lower and not higher.

This push for raising administered prices to reduce the fiscal deficit

is supported by other similarly ''potent'' arguments. For example,

former IMF chief economist and advisor to the Prime Minister, Raghuram

Rajan, has at a function held to release the second edition of a

festschrift in honour of Manmohan Singh, reportedly called for a

complete freeing of diesel prices in order to rein in the fiscal

deficit and boost the confidence of foreign investors.

All this is confusing indeed. It is known that since petroleum products

are in the nature of universal intermediates, increases in their

prices inevitably have a cascading effect on costs and prices of

other commodities and result in an acceleration of inflation. And

since cost-push inflation is unlikely to be smothered by reduced

demand, it would be realised despite any reduction in the fiscal

deficit that may ensue. So, while the RBI is being advised to cautiously

stimulate demand and growth, while keeping a watch on inflation,

the Finance Ministry is being cajoled into stoking inflation by

hiking a range of prices.

This policy muddle is all the more disconcerting since it seems

to be accompanied by a misreading of the inflation scenario. The

case for reducing interest rates is backed by evidence that annual

inflation as measured by month-on-month Wholesale Price Index (WPI)

trends is much below its recent peak and still declining. However,

other evidence suggests that inflation in India still rules high.

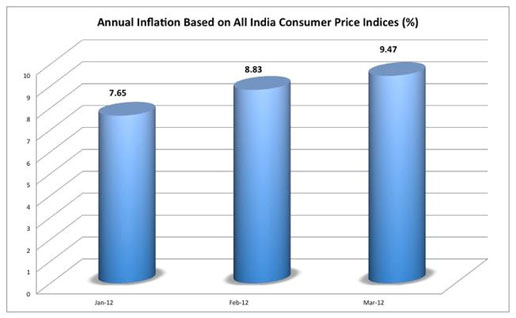

According to the recently released Consumer Price Index (CPI) numbers

for March 2012, the annual month-on-month rate of inflation had

risen to 9.5 per cent from 8.8 per cent in February and 7.7 per

cent in January (see Chart). Since this new series of All India

Consumer Price Indices (with 2010 as base) are being released only

from January 2011, these are the only months for which inflation

figures can be calculated as of now.

Those figures point in two directions. First, that inflation at

the retail level is high and rising, especially because of inflation

in the prices of food articles such as milk and milk products, vegetables,

edible oils and eggs, meat and fish, besides fuels. Second, that

there is a growing divergence in inflation trends based on the WPI,

on the one hand, and the CPI, on the other, with inflation based

on the WPI ruling lower and falling from 7 per cent in February

to 6.9 per cent in March.

To recall, the official justification for the release of the new

CPI series was the argument that the WPI was not reflecting retail

price trends adequately and that inflation measurement based on

retail consumer prices was the international practice. The release

therefore marked the beginning of a transition in which the government

and central bank were to rely on this new index rather than the

WPI to compute the ''benchmark'' inflation rate in the economy.

Preponderant among the goods that enter the nation's consumption

basket and therefore the CPI would be food articles and fuels. The

supply of the former articles is more volatile (because of variable

monsoons, for example) as well as less responsive in the short run

to changes in demand. Their prices, therefore, tend to be more buoyant

than that of most other commodities. On the other hand, because

of political and economic developments in countries contributing

a major part of the world's energy supplies, the fuels component

of the consumption basket is also more ''inflation'' prone than

many other goods. In the event, there is a significant threat of

an acceleration of inflation as measured by the CPI.

Since according to that yardstick inflation is still with us and

would possibly climb, it could be argued that the RBI, which is

convinced that a hike in interest rates is the appropriate weapon

against inflation, was pushed into cutting interest rates at this

point. However, the muddle over policy seems to afflict the RBI

as well. In its recent assessment of Macroeconomic and Monetary

Developments over the last financial year, the central bank has

also come out in favour of increases in petroleum product prices

and other input prices to address the threat posed by ''suppressed

inflation''. That is, since the transmission of international prices

is inevitable, imported inflation can only be suppressed and not

avoided. And, if supressed, inflation is a threat. However, if that

be the case, since further inflation is almost a certainty, the

RBI by its own logic would be forced to reverse its interest rate

reduction decision. Why cut interest rates then?

Perhaps recognising this contradiction the RBI states: ''The upside

risks to inflation on the one hand and the depressed domestic growth

outlook on the other, warrant calibrated measures to maintain a

sustainable balance in a dynamic growth-inflation scenario.'' Presumably,

that is about as clear as one can get.

*

This article was originally published in The Hindu on 20th April

2012 and is available at

http://www.thehindu.com/opinion/columns/Chandrasekhar/article3336278.ece