Themes > Current Issues

04.12.2004

The Dollar Conundrum

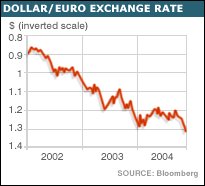

In international markets, all eyes are on the dollar, since uncertainty prevails about the depths to which it would decline. The currency, which appeared to have stabilised relative to the euro in early 2003, after declining from as far back as early 2002, has been sliding sharply since early September. The Financial Times reported on November 26 that the dollar had been through its seventh straight week of losses, falling to multi-year lows against the euro, yen and Swiss franc. Currently close to 1.3 euro and 102 yen to a dollar, the currency still seems heading downwards in the trading days to come.

The

principal factor being quoted to explain the weakness of the dollar

is the $570 billion annual current account deficit on the US balance

of payments. This makes the American appetite for international capital

inflows to finance its balance of payments insatiable. With the US fiscal

deficit running high and delivering output growth even if not jobs,

there is no corrective in sight for the current deficit which is seen

as unsustainable. The difficulty with this argument is that the deficit

in the US balance of payments is not new, nor is it a phenomenon specific

to recent years of rising fiscal deficits. Prior to that, consumer spending,

fuelled by debt, tax-cuts and the so-called "wealth effect"

of a booming stock market, triggered growth. This too was accompanied

by rising trade and current account deficits. Thus, the fundamental

problem is that the US economy is not competitive enough to prevent

a substantial leakage of domestic demand abroad and garner a significant

share of world markets. Growth is inevitably accompanied by external

deficits, making the stimulus required for any given level of domestic

growth that much larger.

For

long this was not seen as a problem. Initially, the position of the

dollar as a reserve currency and the confidence generated by the military

strength of the US made it a safe haven for wealthholders across the

global. Dollar-denominated assets attracted the world's capital and

not just financed the US current account deficit but also fuelled a

stock market boom. Subsequently, countries that had accumulated large

foreign reserves either because of they were successful exporters or

because their imports had been curtailed by deflation, invested these

reserves in dollar assets, especially US Treasury bonds, and helped

finance the external deficit. The dollar remained strong despite the

current account deficit.

The difficulty is that underlying such confidence of public and private

investors is the view that the trade and current account deficits in

the US would somehow take care of themselves, without damaging US growth

substantially. Unfortunately, while growth has been better in the US

than in the euro area and Japan, the deficit has not disappeared but

ballooned. In the circumstance, the only way of curtailing the US trade

deficit seems to be to curtail growth - either by depressing consumer

spending or by slashing the fiscal deficit or both. President Bush and

his team were unwilling to concede on either count prior to his re-election.

And the evidence seems to be that he is not going to immediately wipe

clean the glory his victory has brought by declaring war on US buoyancy.

Bush is not the only one who is unwilling to spoil the party. Alan Greenspan,

who nears the finish of what appeared to be an unending tenure, has

warned that the US current account deficit is unsustainable. But he

too has not shown any keenness to raise interest rates to scorch consumption

and investment spending. What is more, countries which have gained from

the US predicament in the form of large exports to the US market - such

as China - are also not in favour of a US slowdown.

The US has sought to use the last of these by virtually declaring that

its own deficit is not its, but the world's, problem. Countries like

China with a large trade surplus with the US must revalue their currencies

upwards to redress that trade imbalance by exporting less to and importing

more from the US. Other countries, such as those in Europe need to reflate

their economies so as to expand markets for the US. And, finally, all

countries must open doors to their markets by reducing tariffs, so that

the US can ship in more of its commodities. All this, in the US government

view, would help reduce its current account deficit and stabilise the

dollar, without affecting US and, therefore, global growth.

None of these countries are willing to toe that line. China, under pressure

to permit an appreciation of the yuan, has come out quite strongly.

In an interview with the Financial Times, Li Ruogu, the deputy governor

of the People's Bank of China, warned the US not to blame other countries

for its economic difficulties. "China's custom is that we never

blame others for our own problem," he reportedly said. "For

the past 26 years, we never put pressure or problems on to the world.

The US has the reverse attitude, whenever they have a problem, they

blame others."

At the recent G20 meeting, finance ministers and central bank governors

called for a global effort to reduce trade imbalances, and in particular,

the US current account deficit. The rhetoric seemed to be that everybody

should share the costs of that adjustment. John Snow, the US treasury

secretary, chipped in by promising to work towards halving the US budget

deficit and increasing US national saving. But no concrete measures

were on offer.

In sum, there is a degree of global paralysis on the issue of the US

deficit and its impact on global growth. This implies that the only

way in which the external deficit may stop rising and possibly decline

is through a downward adjustment of the dollar, which renders imports

into the US expensive and cheapens US exports.

However, an adjustment of the dollar has been underway not so much because

of any automatic responsiveness to US trade trends, but because of a

growing fear among wealth holders that excess exposure to dollar denominated

assets threatens erosion of the value of that wealth. The gradual adjustment

of private portfolios explains the dollar's decline in the past. More

recently, however, pressure from the dollar has come from a different,

and more powerful, source: the growing unwillingness of central banks

to hold a disproportionate quantity of dollar reserves and risk substantial

losses.

Russian central bank officials have recently declared that they are

likely to adjust the structure of its reserves, estimated at around

$105 billion, by substantially reducing the share of the dollar. Even

a small country like Indonesia with just $35 billion dollars of reserves

has threatened to cut its dollar holding. But the real threat comes

from China with $515 billion in its chest and Japan, which together

account for the bulk of Asia $2.3 billion of reserves. A recent statement

by a Chinese academic, which was quickly retracted, that the rate of

increase of China's holdings of US bonds had fallen and the total was

now around $180 billion, was enough to trigger a slump in the dollar

in jittery markets.

If this trend for policy makers in the US and elsewhere to wait-and-watch

and for wealthholders and central banks to turn cautious on the dollar

persists, the downward slide of the currency is likely to accelerate.

Unfortunately, this would help no one. The appreciation of the euro

and the yen would affect their exports. The slowing of growth in the

US that an enforced cutback in government and private spending and inflation

induced by a falling dollar would result in, would hurt most exporters,

including those from China. And a possible meltdown in US markets is

bound to wipe out a huge quantity of paper wealth that sustains even

the current level of business confidence. Above all, the fragility in

financial markets that the process generates can trigger a liquidity

crunch that would spell deflation.

The fundamental problem is that countries desperate to accelerate or

protect the growth of their own markets and exports, are unwilling to

come together to deal with what is not just a US problem. And their

failure to do so hurts not just the US but the world economy as a whole.

These contradictions in the current global conjuncture reflect the peculiar

nature of US leadership. That leadership is no more attributable to

the relative strength of the US economy, but rather is explained by

the military might of the US and its self-assumed role of global policeman.

However, despite the lack of US economic supremacy, there is a bias

to bilateralism in the global system. The US remains an important market

for most countries, especially the successful exporters like China in

goods and India in services. The US has also been the most favoured

destination for financial investment for private wealthholders and governments.

If countries want this cosy but undeclared relationship with the US

to continue they are bound to be asked to pay a price for the militarism

that makes the US a buoyant economy, a sponge for global exports and

a safe haven for investment. If they are unwilling, they must seek out

strategies that break this undeclared bias to bilateralism that is reminiscent

of colonial times. That would spell an end to US supremacy and the emergence

of a truly multipolar world. However, the transition is not guaranteed.

The costs are likely to be substantial and the outcomes are uncertain.

But perhaps the dollar conundrum signals that there are no mutually

acceptable choices left.

© MACROSCAN 2004