Themes > Current Issues

13.12.2006

Why Inflation Still Matters

Jayati

Ghosh

Perhaps

more than any other purely economic issue, inflation has always been a

pressing socio-political concern in India. That is because the vast majority

of our working people receive incomes that are not indexed to prices,

and are therefore directly and adversely affected especially by the rise

in prices of necessities. Since money wages and the incomes of small businesses

of the self-employed adjust to rising prices only with a lag, this means

that their real incomes get eroded over time. So inflation has direct

income distribution consequences.

Of course, periods of slow price rise are not necessarily always beneficial, even for the poor. If low inflation is the result of restrictive macroeconomic policies that reduce economic activity and employment growth, it can be even worse for the mass of people than moderate inflation rates that are associated with rising aggregate income and employment.

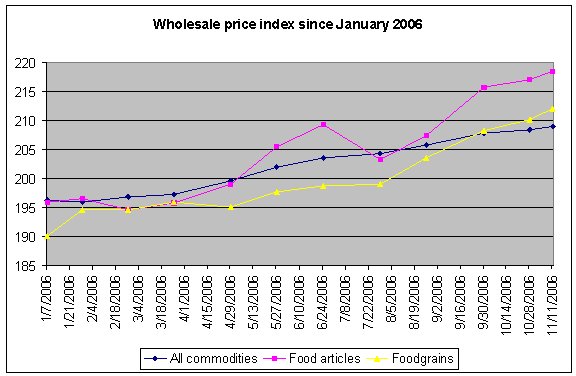

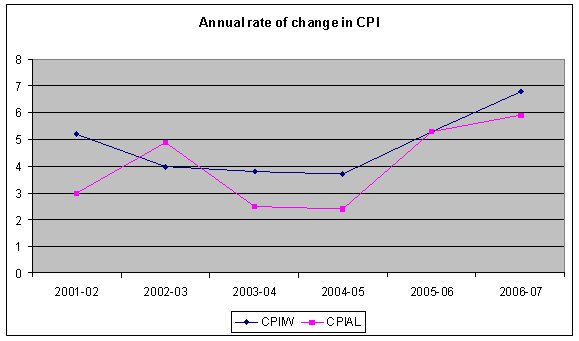

Recent macroeconomic policy discussions have been rather complacent about the issue of inflation in India, especially given the relatively low rates that prevailed over much of the past decade. However, in the past year the increase in the overall inflation rate, as well as the rise in prices of particular commodities, have brought into question both the sustainability of the current economic growth process and the efficacy of public management of price rise in particular sectors.

What has brought about this recent acceleration of inflation in the Indian economy? In a statement before Parliament in July (as reported in the Rajya Sabha proceedings of 24 July 2006) Finance Minister P. Chidambaram claimed this was the result of three forces. According to him, two of these are completely out of the government’s control.

The first factor Mr. Chidambaram described as the cost-push effect emanating from the hardening of world commodity prices, such as oil and other fuels, minerals and metals. With world prices in these increasing, it is only to be expected that domestic prices will also rise. However, in fact global oil prices have been falling in recent times and are now below the levels of even one and a half years ago. The same is true of most agricultural commodities, and of some minerals and metals imported by India. So cost-push inflation because of higher import prices is unlikely to explain the rise in Indian prices after June 2006.

The second factor he mentioned was the demand-pull effect of higher economic growth, which puts pressure on available supplies and therefore leads to what he described as a temporary rise in prices. Certainly there is evidence that rapid growth in some sectors has put pressure on raw material supplies and may lead to supply bottlenecks of particular inputs, including not only raw materials and intermediates, but also some forms of skilled labour.

However, this process – and the resulting price rise - is not a necessary concomitant of high growth. It is worth noting that the Chinese economy has grown very rapidly for nearly thirty years, with only moderate inflation. Even in the current year, when the Chinese economy is apparently growing by more than 10 per cent in real terms, inflation has been only 1.4 per cent at an annual rate. So clearly, rapid growth in domestic demand need not lead to higher inflation.

Further, since China is also a more import-dependent economy than India, importing a greater proportion of inputs for manufacturing production, it should have been more adversely affected by the rise in world commodity prices that Mr Chidambaram spoke of. Instead, inflation rates have been lower than in the past!

The third factor that Mr. Chidambaram mentioned is what he refers to as ''supply shocks'' but which would be better described as poor management of critical areas of the economy. Here, in fact, the Finance Minister probably hit the nail on the head, perhaps inadvertently. He referred to the mismatch between demand and supply in important commodities such as wheat, pulses and sugar, suggesting that unexpected output shortfalls for these crops led to a temporary rise in prices which would get mitigated once supplies were enhanced, for example through imports.

But this is only part of the story. It is misleading to speak only of crop failures, for what happened was essentially a policy-created process that was subsequently mismanaged. The government allowed the entry of large (and multinational) private players into the grain trade, and opened up the futures market for trading in these essential commodities, which all have a history of hoarding. Having thus allowed for speculation, the government was then very surprised when it actually happened.

In wheat, for example, the Food Corporation of India was unable to procure adequate amounts for the public distribution system because private players like Cargill were offering higher prices to the farmers. Procurement declined by nearly 40 per cent compared to last year and wheat stocks fell by 20 per cent to less than 7 million tonnes. This was not only inadequate for the requirements of the government in terms of the PDS and school meals programmes, but also insufficient to quell speculative activity in wheat markets when prices started to rise.

Eventually, the government was forced to import wheat at prices several times higher than what it had been willing to pay Indian farmers, and in the meantime consumers had to cope with rising prices of wheat. A similar story operates for pulses, except that mitigating imports have not yet occurred so the price rise continues unabated.

This is such expensive incompetence that in any country with real democratic accountability, heads would have rolled over this. But in India, ministers can talk glibly of ''supply-demand imbalances'' as if these were somehow completely outside the purview of government.

The government is indeed now concerned about inflation, but unfortunately the knee-jerk response has been to use the blunt instrument of the interest rate. In the past months, the RBI’s discount rate has been increased three times, most recently on October 31. But this affects all productive sectors alike, and has disproportionately negative effects upon small enterprises that already find it more difficult to get bank credit.

Instead of this blanket measure there should have been more nuanced and directed interventions addressing the sectors in which speculative bubbles are clearly visible. The stock market, for example, continues to be irrationally exuberant, and the imposition of a capital gains tax at this point could only have a salutary effect, besides raising more revenue for the government. The real estate market is clearly overheating – house prices in the metros are estimated to have more than doubled in the past two years. Yet the banking system and the income tax structure continue to encourage property loans.

Clearly, the recent rise in inflation reflects not higher growth but just economic mismanagement.

Of course, periods of slow price rise are not necessarily always beneficial, even for the poor. If low inflation is the result of restrictive macroeconomic policies that reduce economic activity and employment growth, it can be even worse for the mass of people than moderate inflation rates that are associated with rising aggregate income and employment.

Recent macroeconomic policy discussions have been rather complacent about the issue of inflation in India, especially given the relatively low rates that prevailed over much of the past decade. However, in the past year the increase in the overall inflation rate, as well as the rise in prices of particular commodities, have brought into question both the sustainability of the current economic growth process and the efficacy of public management of price rise in particular sectors.

What has brought about this recent acceleration of inflation in the Indian economy? In a statement before Parliament in July (as reported in the Rajya Sabha proceedings of 24 July 2006) Finance Minister P. Chidambaram claimed this was the result of three forces. According to him, two of these are completely out of the government’s control.

The first factor Mr. Chidambaram described as the cost-push effect emanating from the hardening of world commodity prices, such as oil and other fuels, minerals and metals. With world prices in these increasing, it is only to be expected that domestic prices will also rise. However, in fact global oil prices have been falling in recent times and are now below the levels of even one and a half years ago. The same is true of most agricultural commodities, and of some minerals and metals imported by India. So cost-push inflation because of higher import prices is unlikely to explain the rise in Indian prices after June 2006.

The second factor he mentioned was the demand-pull effect of higher economic growth, which puts pressure on available supplies and therefore leads to what he described as a temporary rise in prices. Certainly there is evidence that rapid growth in some sectors has put pressure on raw material supplies and may lead to supply bottlenecks of particular inputs, including not only raw materials and intermediates, but also some forms of skilled labour.

However, this process – and the resulting price rise - is not a necessary concomitant of high growth. It is worth noting that the Chinese economy has grown very rapidly for nearly thirty years, with only moderate inflation. Even in the current year, when the Chinese economy is apparently growing by more than 10 per cent in real terms, inflation has been only 1.4 per cent at an annual rate. So clearly, rapid growth in domestic demand need not lead to higher inflation.

Further, since China is also a more import-dependent economy than India, importing a greater proportion of inputs for manufacturing production, it should have been more adversely affected by the rise in world commodity prices that Mr Chidambaram spoke of. Instead, inflation rates have been lower than in the past!

The third factor that Mr. Chidambaram mentioned is what he refers to as ''supply shocks'' but which would be better described as poor management of critical areas of the economy. Here, in fact, the Finance Minister probably hit the nail on the head, perhaps inadvertently. He referred to the mismatch between demand and supply in important commodities such as wheat, pulses and sugar, suggesting that unexpected output shortfalls for these crops led to a temporary rise in prices which would get mitigated once supplies were enhanced, for example through imports.

But this is only part of the story. It is misleading to speak only of crop failures, for what happened was essentially a policy-created process that was subsequently mismanaged. The government allowed the entry of large (and multinational) private players into the grain trade, and opened up the futures market for trading in these essential commodities, which all have a history of hoarding. Having thus allowed for speculation, the government was then very surprised when it actually happened.

In wheat, for example, the Food Corporation of India was unable to procure adequate amounts for the public distribution system because private players like Cargill were offering higher prices to the farmers. Procurement declined by nearly 40 per cent compared to last year and wheat stocks fell by 20 per cent to less than 7 million tonnes. This was not only inadequate for the requirements of the government in terms of the PDS and school meals programmes, but also insufficient to quell speculative activity in wheat markets when prices started to rise.

Eventually, the government was forced to import wheat at prices several times higher than what it had been willing to pay Indian farmers, and in the meantime consumers had to cope with rising prices of wheat. A similar story operates for pulses, except that mitigating imports have not yet occurred so the price rise continues unabated.

This is such expensive incompetence that in any country with real democratic accountability, heads would have rolled over this. But in India, ministers can talk glibly of ''supply-demand imbalances'' as if these were somehow completely outside the purview of government.

The government is indeed now concerned about inflation, but unfortunately the knee-jerk response has been to use the blunt instrument of the interest rate. In the past months, the RBI’s discount rate has been increased three times, most recently on October 31. But this affects all productive sectors alike, and has disproportionately negative effects upon small enterprises that already find it more difficult to get bank credit.

Instead of this blanket measure there should have been more nuanced and directed interventions addressing the sectors in which speculative bubbles are clearly visible. The stock market, for example, continues to be irrationally exuberant, and the imposition of a capital gains tax at this point could only have a salutary effect, besides raising more revenue for the government. The real estate market is clearly overheating – house prices in the metros are estimated to have more than doubled in the past two years. Yet the banking system and the income tax structure continue to encourage property loans.

Clearly, the recent rise in inflation reflects not higher growth but just economic mismanagement.

© MACROSCAN 2006