Themes > Current Issues

18.12.2006

Being Your Own Boss

Jayati

Ghosh

There

are important changes taking place in labour markets in India. The results

of the latest large round of the National Sample Survey Organisation,

which took place in 2004-05, have just been released. They reveal some

significant changes in the employment patterns and conditions of work

in India over the first half of this decade.

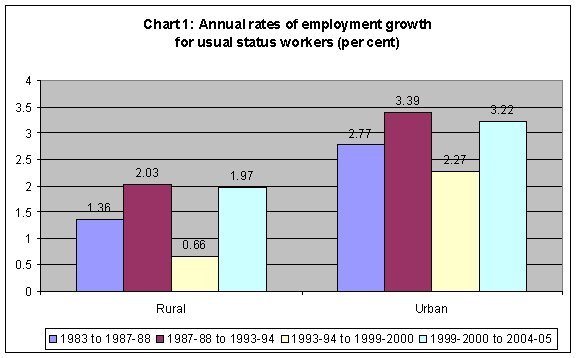

First, aggregate employment has been growing again. The first important change from the previous period relates to aggregate employment growth itself. The late 1990s was a period of sharp deceleration of aggregate employment generation, which fell to the lowest rate recorded since such data began being collected in the 1950s. However, the most recent period indicates a recovery, as shown in Chart 1.

At the same time, however, unemployment rates have also been increasing, and are now the highest ever recorded. Unemployment measured by current daily status, which describes the pattern on a typical day of the previous week, accounted for 8 per cent of the male labour force in both urban and rural India, and between 9 and 12 per cent of the female labour force, which is truly remarkable, and very worrying in a country that provides nothing in the form of unemployment benefit or insurance.

But perhaps the most significant change of has been in the pattern of employment. There has been a significant decline in wage employment in general, which includes both regular contracts and casual work. While regular employment had been declining as a share of total usual status employment for some time now (except for urban women workers), wage employment had continued to grow in share because employment on casual contracts had been on the increase.

But the latest survey round suggests that even casual employment has fallen in proportion to total employment. In fact, the share of casual labour has fallen for all categories of workers - men and women, in rural and urban India. The sharpest decline has been in agriculture, where wage employment in general has fallen by a rate of more than 3 per cent per year between 1999-2000 and 2004-05.

But even for urban male workers, total wage employment is now the lowest that it has been in at least two decades, driven by declines in both regular and casual paid work. For women, in both rural and urban areas, the share of regular work has increased but that of casual employment has fallen so sharply that the aggregate share of wage employment has fallen. So there is clearly a real and increasing difficulty among the working population, of finding paid jobs in any form.

This is probably the real reason why there has been a very significant increase in self-employment among all categories of workers in India. The increase has been sharpest among rural women, where self-employment now accounts for nearly two-thirds of all jobs. But it is also remarkable for urban workers, both men and women, among whom the self-employed constitute 45 and 48 per cent respectively, of all usual status workers.

All told, therefore, around half of the work force in India currently does not work for a direct employer. This is true not only in agriculture, but increasingly in a wide range of non-agricultural activities, and in both rural and urban areas.

Self-employment is often eulogised as representing an advance from the drudgery of paid work and the possibly tyranny of employers. And of course there are cases where self-employment is of this preferable and more liberated variety, where the joys of being one’s own boss more than compensate for the increased insecurity of income and greater difficulties of arranging the sale of one’s produced goods or services.

But the particular context in which self-employment has arisen in India in recent years suggests that these more positive experiences may account for only a minority of increase in self-employment. Instead, more and more working people are forced to work for themselves because they simply cannot find paid jobs. In the case of less educated workers without access to capital or bank credit, this in turn means that they are forced into petty low productivity activities with low and uncertain incomes.

The latest NSS report confirms this, with some very interesting information about whether those in self-employment actually perceive their activities to be remunerative. It turns out that just under half of all self-employed workers do not find their work to be remunerative. This is despite very low expectations of reasonable returns - more than 40 per cent of rural workers declared they would have been satisfied with earning less than Rs. 1500 per month, while one-third of urban workers would have found Rs. 2000 to be remunerative.

This new trend requires a significant rethinking of the way analysts, policy makers and activists deal with the notion of ''workers''. The older categories, methods of analysis and policies become largely irrelevant in this context.

For example, how does one ensure decent conditions of work when the absence of a direct employer means that self-exploitation by workers in a competitive market is the greater danger? How do we assess and ensure ''living wages'' when wages are not received at all by such workers, who instead depend upon uncertain returns from various activities that are typically petty in nature? What are the possible forms of policy intervention to improve work conditions and strategies of worker mobilisation in this context?

This significance of self-employment also brings home the urgent need to consider basic social security that covers not just hired workers in the unorganised sector, but also those who typically work for themselves. This makes the pending legislation on social security for workers in the unorganised sector especially important. It is time we revised our labour policies to deal more effectively with the changing circumstances.

First, aggregate employment has been growing again. The first important change from the previous period relates to aggregate employment growth itself. The late 1990s was a period of sharp deceleration of aggregate employment generation, which fell to the lowest rate recorded since such data began being collected in the 1950s. However, the most recent period indicates a recovery, as shown in Chart 1.

At the same time, however, unemployment rates have also been increasing, and are now the highest ever recorded. Unemployment measured by current daily status, which describes the pattern on a typical day of the previous week, accounted for 8 per cent of the male labour force in both urban and rural India, and between 9 and 12 per cent of the female labour force, which is truly remarkable, and very worrying in a country that provides nothing in the form of unemployment benefit or insurance.

But perhaps the most significant change of has been in the pattern of employment. There has been a significant decline in wage employment in general, which includes both regular contracts and casual work. While regular employment had been declining as a share of total usual status employment for some time now (except for urban women workers), wage employment had continued to grow in share because employment on casual contracts had been on the increase.

But the latest survey round suggests that even casual employment has fallen in proportion to total employment. In fact, the share of casual labour has fallen for all categories of workers - men and women, in rural and urban India. The sharpest decline has been in agriculture, where wage employment in general has fallen by a rate of more than 3 per cent per year between 1999-2000 and 2004-05.

But even for urban male workers, total wage employment is now the lowest that it has been in at least two decades, driven by declines in both regular and casual paid work. For women, in both rural and urban areas, the share of regular work has increased but that of casual employment has fallen so sharply that the aggregate share of wage employment has fallen. So there is clearly a real and increasing difficulty among the working population, of finding paid jobs in any form.

This is probably the real reason why there has been a very significant increase in self-employment among all categories of workers in India. The increase has been sharpest among rural women, where self-employment now accounts for nearly two-thirds of all jobs. But it is also remarkable for urban workers, both men and women, among whom the self-employed constitute 45 and 48 per cent respectively, of all usual status workers.

All told, therefore, around half of the work force in India currently does not work for a direct employer. This is true not only in agriculture, but increasingly in a wide range of non-agricultural activities, and in both rural and urban areas.

Self-employment is often eulogised as representing an advance from the drudgery of paid work and the possibly tyranny of employers. And of course there are cases where self-employment is of this preferable and more liberated variety, where the joys of being one’s own boss more than compensate for the increased insecurity of income and greater difficulties of arranging the sale of one’s produced goods or services.

But the particular context in which self-employment has arisen in India in recent years suggests that these more positive experiences may account for only a minority of increase in self-employment. Instead, more and more working people are forced to work for themselves because they simply cannot find paid jobs. In the case of less educated workers without access to capital or bank credit, this in turn means that they are forced into petty low productivity activities with low and uncertain incomes.

The latest NSS report confirms this, with some very interesting information about whether those in self-employment actually perceive their activities to be remunerative. It turns out that just under half of all self-employed workers do not find their work to be remunerative. This is despite very low expectations of reasonable returns - more than 40 per cent of rural workers declared they would have been satisfied with earning less than Rs. 1500 per month, while one-third of urban workers would have found Rs. 2000 to be remunerative.

This new trend requires a significant rethinking of the way analysts, policy makers and activists deal with the notion of ''workers''. The older categories, methods of analysis and policies become largely irrelevant in this context.

For example, how does one ensure decent conditions of work when the absence of a direct employer means that self-exploitation by workers in a competitive market is the greater danger? How do we assess and ensure ''living wages'' when wages are not received at all by such workers, who instead depend upon uncertain returns from various activities that are typically petty in nature? What are the possible forms of policy intervention to improve work conditions and strategies of worker mobilisation in this context?

This significance of self-employment also brings home the urgent need to consider basic social security that covers not just hired workers in the unorganised sector, but also those who typically work for themselves. This makes the pending legislation on social security for workers in the unorganised sector especially important. It is time we revised our labour policies to deal more effectively with the changing circumstances.

© MACROSCAN 2006