Themes > Current Issues

21.02.2004

Is Indian Industry Shining?

The

deliberate adoption of a myopic vision is writ large in the India Shining

campaign, with its principal focus on a successful, urban, middle India.

This effort to manipulate perspective is revealed in the use of figures

of economic performance in a single year or a couple of selectively chosen

ones to cloud events of even the immediate past. It is reflected in the

tendency to emphasise and elevate the double effect of speculative FII

inflows in sharply increasing India's foreign exchange reserves position

on the one hand, and triggering a boom (however volatile) in India's stock

market on the other, while ignoring the poor performance of the commodity

producing sectors. It is seen in the effort to celebrate new, and yet

marginal, trends in employment while downplaying the devastation that

poor agricultural labourers and small farmers must have faced because

of the drought in 2002-03, whose effects on production was far more severe

than any prediction – official or otherwise. A typical example of such

new trends is the rapid rise, albeit from a small base, in employment

and revenues from IT-enabled services like call centres, that have reportedly

generated jobs for around 1,70,000-2,00,000 young Indians.

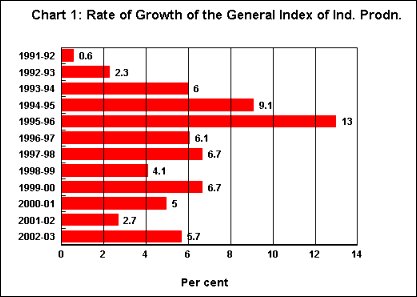

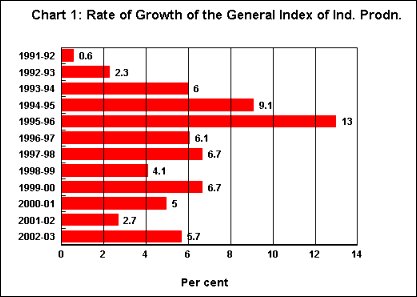

The effects of this myopic vision are seen in the approach to all sectors of the economy. Consider, for example, industry. Conventionally urban prosperity was linked to the advance of a dynamic industrial sector. Unfortunately, going by the figures on the Index of Industrial Production, industrial growth was at an unremarkable 6.3 per cent during the first nine months of so-called boom year 2003-04, when agricultural production shot back from its 2002-03 trough.

During the peak of the liberalization and reform euphoria in 1994-95 and 1995-96, respectively, industrial growth was at 9.1 and 13 per cent respectively, well before the NDA's magic ostensibly began to transform this country. The lack of dynamism that this decline in industrial growth since the early mid-1990s reflects is all the more disturbing because it combines with an overall stagnation in the investment rate in a country that is supposedly on the move and is the darling of foreign investors.

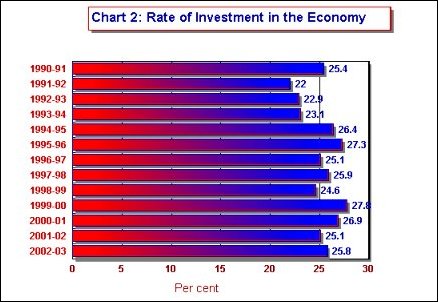

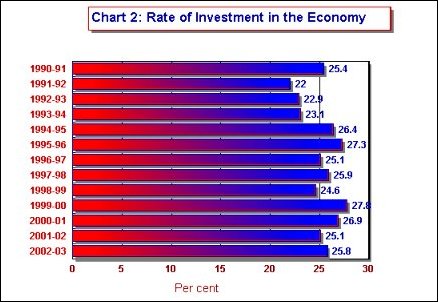

As Chart 2 indicates, after rising in the first half of the 1990s to touch a peak of 27.3 per cent in 1995-96, the rate of capital formation in the economy has remained well below that level in all but one of the subsequent years. This decline and subsequent stagnation in investment occurs despite the visible signs of movement, in sectors like telecom and more recently in highway construction – sectors that the Prime Minister has identified as epitomising the direction the rest of India should take. What he missed out was the fact that investment in these sectors, at whatever rates they are actually occurring, failed to pull along investment in the rest of the economy. Conventionally, through its effects on profits and utilisation in the rest of the economy, future investment is triggered elsewhere. This, Shining India has not been able to ensure. Clearly, if investment is not buoyant, an economy could not be. Seen from the angle of vision of the principal commodity producing sector, what is happening is that the early gloss is fading under the NDA.

The lack of investment has been accompanied by dismal trends in employment over the 1990s, despite the Planning Commission's propagandist claims of the government having "created" 84 lakh jobs every year over the last years. This intriguing claim, it now appears, is based on a comparison of the "usual status" workforce figures yielded by two NSS surveys relating to July-June 2000 and July-December 2002, which have as their mid-points the two dates (1 January 2000 and 1 October 2002) that provide the 33-month period for which the claim is being made. As Prof. K. Sundaram from the Delhi School of Economics has pointed out (Economic Times, 14 February 2004), there are a number of problems with using these surveys for such short term comparisons. Thus, the NSS surveys seem to suggest that employment increased by 76 lakh (not 84 lakh as claimed) in the 33-month period between 1 January 2000 and 1 October 2002, 68 lakh in the 21-month between 1 January 2001 and 1 October 2002, and 300 lakh in the 24-month period between 1 January 2000 and 1 January 2002, while it declined by 90 lakh in the 9-month between 1 January 2002 and 1 October 2002. If the last of these is used as the basis for judgement, Indian is clearly not shining more recently. Given the specific focus of each round of the NSS, using the figures yielded for such short term comparisons may not be the best way to assess increases (or decreases) in absolute employment.

But that this is not all. Even if we stick by the two surveys and the two time points used by the Planning Commission in its advertisement, which claims that in the last three years "we" are getting close to achieving the Prime Minister's target of providing one crore new employment opportunities every year, the evidence on "whose India is shining" is quite damaging. First, urban areas which account for 23 per cent of the workforce account for 40 per cent of the increase in "employment opportunities" during the 33-month period. Second, the number of women workers in the country declined by 15 lakh or around 5 lakh per annum. Third, this decline in the case of women in rural areas amounted to close to 10 lakh per annum. Fourth, the number of women workers in the 15-34 age group declined by 17 lakh per annum. Finally, the share of all those in the 15-34 age group (who feature prominently in the India Shining campaign) in the new employment opportunities claimed to have been created amounted to just 25 per cent, whereas those aged '60 and above' accounted for around 17 per cent. Once we take note of these figures, little needs to be said about the dismal "quality" of the "employment opportunities" that the government claims to have created.

These trends, in output, investment and employment are indeed surprising given the fact that this has been the period when huge concessions and tax benefits have been handed out to India's corporate sector with the aim of reviving the animal spirits of India's dormant monopoly groups and kick-starting investment. The spur to industry does not stop there. It also comes from the consumption and housing finance boom that has been spurred by the reckless lending at declining interest rates that financial liberalisation has resulted in. According to reports on a study undertaken by KSA Technopak, personal credit outstanding in the country rose by 300 per cent from Rs. 40,000 crores in 2000 to Rs.1,60,000 crores in 2003 and is still growing. Though this still accounts for only 12-14 per cent of aggregate consumption spending in the country, its concentration among the "middle class", especially in urban India, would imply that there is a growing credit overhang that is based on excessive exposure to a small section of the population. These are also the sections which are being provided large volumes of housing finance at low nominal interest rates by financial firms desperate to find vents for the liquidity that they can access. The Reserve Bank of India has already warned housing finance companies about the high risk portfolio that many of them are carrying.

This credit boom may be increasing fragility in India's increasingly liberalised financial sector. But it is also helping along sales volumes in corporate India and holding up profits. The problem however is that having bought earlier versions of the India Shining campaign, corporate India has created so much excess capacity in many areas that the increases in demand only go to increase utilisation of already created capacities, and has not helped spur investment in recent times.

However, combined with the concessions that have been handed out to the private sector that we referred to earlier, these trends have indeed helped the corporate sector declare reasonably high profits. This is one more recent trend that provides the gloss for India's shine. Those profits and the fact that India is the flavour of the season for foreign institutional investors have provided the basis for a spurt of speculation in the stock markets taking the Sensex to new temporal highs, even if this is accompanied by substantial volatility. Therefore, the Sensex has become one more barometer for a government in search of the shine that is constantly rendered murky by visible signs of poverty.

That search has been successful also because of another consequence of the stock market rush: the surge of FII investments in the country that have contributed substantially to the sharp and sudden increase in the size of India's foreign exchange reserves. Having crossed the $100 billion mark, those reserves have become a source of embarrassment and a problem for the government. Embarrassment because those reserves, which arise because of RBI purchases of foreign exchange to prevent the rupee from appreciating and affecting India's export competitiveness adversely, are now being cited as evidence of the fact that the rupee is "undervalued". Revalue the rupee, the US argues, so that imports are not discriminated against in the Indian market.

The reserves are also a problem because, while the inflows that deliver them earn high returns that can be repatriated in foreign exchange, their investment abroad yields the country a less than 3 per cent average return. This implies that the country is paying a high price in foreign exchange in order to accumulate and maintain such reserves. To boot, the inflows that contribute these reserves are in the nature of "hot money" flows. If and when foreign investors begin to suspect that the shine was never there, there could be a rush of investment out of the country. Since the government, egged on by the reserves, has decided to encourage profligate foreign exchange spending and investments abroad by ordinary citizens who have the wherewithal, any such exit would soon turn into an exodus, precipitating a financial crisis of a kind that the world is all too familiar with.

Unwarranted claims in all these areas is sought to be strengthened by figures of recent performance. But even here the lie is hard to sell. It is indeed true that growth this year in agriculture has been remarkable. But that clearly is because of the bad monsoon-induced collapse of agricultural output that makes a return to output levels achieved in 2001-02 deliver a remarkable growth rate. It is true that the recovery in agriculture combined with a credit-driven spending boom has helped industrial growth along. But that growth is far short of what the advocates of liberalisation promised to deliver and did manage to do so for a brief period in the mid-1990s when the NDA was yet to take power. It is true that the software and IT-enabled services sector is witnessing high rates of growth of revenues, exports and employment. But that occurs on a low base in a sector which remains an enclave and cannot compensate for the slow growth in the commodity producing sectors. It is also true that India's foreign exchange reserve position, its stock markets and its financial sector are buoyant. But all that also reflects the fragility that underlies the kind of jobless growth process that the NDA government has unleashed during its tenure.

Why is the government choosing to manipulate the nation's vision by behaving as if what it says is true? It should be obvious that the real intent of the India Shining slogan is to conceal the poor performance of the commodity producing sectors and the fragility of much else of the economy. If India's economy is shining, that shine is similar to the light reflected off an overblown bubble. The coming election, therefore, is also one that would decide who would pick up the pieces when that bubble does burst.

The effects of this myopic vision are seen in the approach to all sectors of the economy. Consider, for example, industry. Conventionally urban prosperity was linked to the advance of a dynamic industrial sector. Unfortunately, going by the figures on the Index of Industrial Production, industrial growth was at an unremarkable 6.3 per cent during the first nine months of so-called boom year 2003-04, when agricultural production shot back from its 2002-03 trough.

During the peak of the liberalization and reform euphoria in 1994-95 and 1995-96, respectively, industrial growth was at 9.1 and 13 per cent respectively, well before the NDA's magic ostensibly began to transform this country. The lack of dynamism that this decline in industrial growth since the early mid-1990s reflects is all the more disturbing because it combines with an overall stagnation in the investment rate in a country that is supposedly on the move and is the darling of foreign investors.

As Chart 2 indicates, after rising in the first half of the 1990s to touch a peak of 27.3 per cent in 1995-96, the rate of capital formation in the economy has remained well below that level in all but one of the subsequent years. This decline and subsequent stagnation in investment occurs despite the visible signs of movement, in sectors like telecom and more recently in highway construction – sectors that the Prime Minister has identified as epitomising the direction the rest of India should take. What he missed out was the fact that investment in these sectors, at whatever rates they are actually occurring, failed to pull along investment in the rest of the economy. Conventionally, through its effects on profits and utilisation in the rest of the economy, future investment is triggered elsewhere. This, Shining India has not been able to ensure. Clearly, if investment is not buoyant, an economy could not be. Seen from the angle of vision of the principal commodity producing sector, what is happening is that the early gloss is fading under the NDA.

The lack of investment has been accompanied by dismal trends in employment over the 1990s, despite the Planning Commission's propagandist claims of the government having "created" 84 lakh jobs every year over the last years. This intriguing claim, it now appears, is based on a comparison of the "usual status" workforce figures yielded by two NSS surveys relating to July-June 2000 and July-December 2002, which have as their mid-points the two dates (1 January 2000 and 1 October 2002) that provide the 33-month period for which the claim is being made. As Prof. K. Sundaram from the Delhi School of Economics has pointed out (Economic Times, 14 February 2004), there are a number of problems with using these surveys for such short term comparisons. Thus, the NSS surveys seem to suggest that employment increased by 76 lakh (not 84 lakh as claimed) in the 33-month period between 1 January 2000 and 1 October 2002, 68 lakh in the 21-month between 1 January 2001 and 1 October 2002, and 300 lakh in the 24-month period between 1 January 2000 and 1 January 2002, while it declined by 90 lakh in the 9-month between 1 January 2002 and 1 October 2002. If the last of these is used as the basis for judgement, Indian is clearly not shining more recently. Given the specific focus of each round of the NSS, using the figures yielded for such short term comparisons may not be the best way to assess increases (or decreases) in absolute employment.

But that this is not all. Even if we stick by the two surveys and the two time points used by the Planning Commission in its advertisement, which claims that in the last three years "we" are getting close to achieving the Prime Minister's target of providing one crore new employment opportunities every year, the evidence on "whose India is shining" is quite damaging. First, urban areas which account for 23 per cent of the workforce account for 40 per cent of the increase in "employment opportunities" during the 33-month period. Second, the number of women workers in the country declined by 15 lakh or around 5 lakh per annum. Third, this decline in the case of women in rural areas amounted to close to 10 lakh per annum. Fourth, the number of women workers in the 15-34 age group declined by 17 lakh per annum. Finally, the share of all those in the 15-34 age group (who feature prominently in the India Shining campaign) in the new employment opportunities claimed to have been created amounted to just 25 per cent, whereas those aged '60 and above' accounted for around 17 per cent. Once we take note of these figures, little needs to be said about the dismal "quality" of the "employment opportunities" that the government claims to have created.

These trends, in output, investment and employment are indeed surprising given the fact that this has been the period when huge concessions and tax benefits have been handed out to India's corporate sector with the aim of reviving the animal spirits of India's dormant monopoly groups and kick-starting investment. The spur to industry does not stop there. It also comes from the consumption and housing finance boom that has been spurred by the reckless lending at declining interest rates that financial liberalisation has resulted in. According to reports on a study undertaken by KSA Technopak, personal credit outstanding in the country rose by 300 per cent from Rs. 40,000 crores in 2000 to Rs.1,60,000 crores in 2003 and is still growing. Though this still accounts for only 12-14 per cent of aggregate consumption spending in the country, its concentration among the "middle class", especially in urban India, would imply that there is a growing credit overhang that is based on excessive exposure to a small section of the population. These are also the sections which are being provided large volumes of housing finance at low nominal interest rates by financial firms desperate to find vents for the liquidity that they can access. The Reserve Bank of India has already warned housing finance companies about the high risk portfolio that many of them are carrying.

This credit boom may be increasing fragility in India's increasingly liberalised financial sector. But it is also helping along sales volumes in corporate India and holding up profits. The problem however is that having bought earlier versions of the India Shining campaign, corporate India has created so much excess capacity in many areas that the increases in demand only go to increase utilisation of already created capacities, and has not helped spur investment in recent times.

However, combined with the concessions that have been handed out to the private sector that we referred to earlier, these trends have indeed helped the corporate sector declare reasonably high profits. This is one more recent trend that provides the gloss for India's shine. Those profits and the fact that India is the flavour of the season for foreign institutional investors have provided the basis for a spurt of speculation in the stock markets taking the Sensex to new temporal highs, even if this is accompanied by substantial volatility. Therefore, the Sensex has become one more barometer for a government in search of the shine that is constantly rendered murky by visible signs of poverty.

That search has been successful also because of another consequence of the stock market rush: the surge of FII investments in the country that have contributed substantially to the sharp and sudden increase in the size of India's foreign exchange reserves. Having crossed the $100 billion mark, those reserves have become a source of embarrassment and a problem for the government. Embarrassment because those reserves, which arise because of RBI purchases of foreign exchange to prevent the rupee from appreciating and affecting India's export competitiveness adversely, are now being cited as evidence of the fact that the rupee is "undervalued". Revalue the rupee, the US argues, so that imports are not discriminated against in the Indian market.

The reserves are also a problem because, while the inflows that deliver them earn high returns that can be repatriated in foreign exchange, their investment abroad yields the country a less than 3 per cent average return. This implies that the country is paying a high price in foreign exchange in order to accumulate and maintain such reserves. To boot, the inflows that contribute these reserves are in the nature of "hot money" flows. If and when foreign investors begin to suspect that the shine was never there, there could be a rush of investment out of the country. Since the government, egged on by the reserves, has decided to encourage profligate foreign exchange spending and investments abroad by ordinary citizens who have the wherewithal, any such exit would soon turn into an exodus, precipitating a financial crisis of a kind that the world is all too familiar with.

Unwarranted claims in all these areas is sought to be strengthened by figures of recent performance. But even here the lie is hard to sell. It is indeed true that growth this year in agriculture has been remarkable. But that clearly is because of the bad monsoon-induced collapse of agricultural output that makes a return to output levels achieved in 2001-02 deliver a remarkable growth rate. It is true that the recovery in agriculture combined with a credit-driven spending boom has helped industrial growth along. But that growth is far short of what the advocates of liberalisation promised to deliver and did manage to do so for a brief period in the mid-1990s when the NDA was yet to take power. It is true that the software and IT-enabled services sector is witnessing high rates of growth of revenues, exports and employment. But that occurs on a low base in a sector which remains an enclave and cannot compensate for the slow growth in the commodity producing sectors. It is also true that India's foreign exchange reserve position, its stock markets and its financial sector are buoyant. But all that also reflects the fragility that underlies the kind of jobless growth process that the NDA government has unleashed during its tenure.

Why is the government choosing to manipulate the nation's vision by behaving as if what it says is true? It should be obvious that the real intent of the India Shining slogan is to conceal the poor performance of the commodity producing sectors and the fragility of much else of the economy. If India's economy is shining, that shine is similar to the light reflected off an overblown bubble. The coming election, therefore, is also one that would decide who would pick up the pieces when that bubble does burst.

© MACROSCAN 2004