Inflation

that had been officially declared as being on the

wane is back and raging. Focused on food articles,

it is eroding the real incomes of the already poor

and, therefore, the popular support which brought

UPA II to power. Particularly damaging is the fact

that high inflation has been the norm for a year now,

with its incidence shifting across commodities, but

most often falling on one or other set of food articles.

The government seems to be helpless and just wishing

that the problem would go away. Almost a year ago,

when addressing a Chief Minister's conference on food

prices early in February 2010, Prime Minister Manmohan

Singh declared: "The worst is over as far as

food inflation is concerned. I am confident that we

will soon be able to stabilise food prices."

Three months later, on more than one occasion, government

spokespersons, like Chief Economic Advisor Kaushik

Basu, had declared that inflation had ''peaked out''

and was on a downward trend. Such statements are not

surprising since in the current dispensation government

representatives at the highest level are expected

to talk down prices and talk up markets. It is not

what you say but the confidence with which you say

it that matters.

But there is reason to believe that the government

did actually believe that inflation would follow some

sort of a cycle, and more likely moderate quickly

than rise significanty. One or two predictions of

an impending price decline are understandable. But,

over the last year, almost every month or even week,

one official spokesperson or the other (be it the

Finance Minister, the Finance Secretary, the Deputy

Chairman of the Planning Commission or the ubiquitous

head of the PM's Economic Advisory Council) declared

that inflation is bound to moderate, in a voice tinged

with surprise that it has not done so earlier.

This expectation came from a particular reading of

the situation. Whenever prices did rise rapidly, it

was attributed either to supply side factors such

as a poor crop or to unavoidable factors like the

''base effect''. Thus when the PM spoke in February

last year he looked forward to a good monsoon and

a better crop. And, if prices had been unusually low

a year earlier, even a return to ''normalcy'' would

reflect a high rate of inflation that must be discounted.

Occasionally, of course, there was talk of hoarding

and speculation, but only on the part of unscrupulous

traders, who were exploiting temporary demand-supply

imbalances.

Experience has shown that these ''beliefs'' were patently

false. Despite the fact that the monsoon has been

much better in recent seasons, the annual point-to-point

inflation in the Wholesale Price Index for Food Articles

stood at 18.32 per cent and 16.91 per cent during

the weeks ending December 25, 2010 and January 1,

2011. The figures for the corresponding weeks of the

previous year were 19.9 per cent and 19.6 per cent.

Not much has changed even though the commodities involved

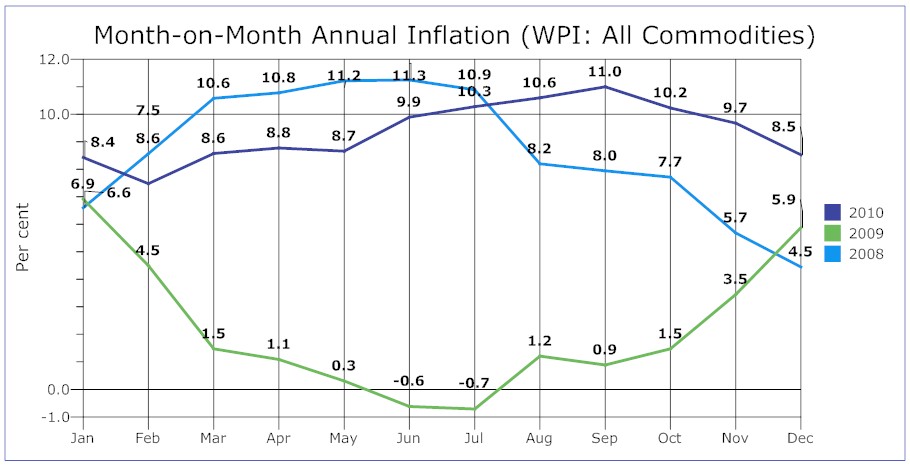

are slightly different. Moreover, the month-on-month

inflation rate as reflected even by the Wholesale

Price Index for All Commodities, which stood at a

disconcertingly high level in the first half of 2008,

and then declined consistently between July 2008 and

July 2009, accelerated subsequently and has remained

at high levels throughout 2010. The month-on-month

rate of inflation stood at 9.7 per cent in November

and 8.5 per cent in December. And if weekly WPI movements

are an indication, this is likely to be true in January

2011 as well. The consumer price indices for agricultural

labourers and industrial workers, which reflect the

movements in the basket of goods consumed by these

sections (which includes housing that dampens the

increase) also rose by 7.1 per cent and 8.3 per cent

respectively in November relative to the corresponding

month of the previous year.

Chart

1 >> Click

to Enlarge

This persistence of the inflationary trend is substantially

because the government, while occasionally expressing

concern over the high level of inflation, has done

little to combat it, given its belief that inflation

will necessarily moderate when supply conditions improve

or the base effect wears out. This has sent out the

message that economic governance under a government

populated with economists of repute has broken down.

That impression has only been bolstered by the open

spats between segments of the government over who

is responsible for the persisting inflation.

To understand the factors that could be driving the

price rise, we need to turn to a number of noteworthy

features of the current inflation scenario. The first

is that, while it is not restricted to food alone,

it has been substantially driven by food articles,

which are more prone to speculative influences. In

the case of these commodities, even when demand-supply

imbalances are minor or absent, speculation can push

up prices. The second is that within food articles,

inflation has at different points in time affected

different commodities, such as cereals, pulses, vegetables,

eggs, meat and milk. Not all of these commodities

are equally weather dependent and the prices of some

are influenced by how administered prices are set.

To attribute the trends in their prices solely to

demand-supply imbalances or imported inflation is

to avoid the conundrum. Third, when inflation does

occur in some food items, be they onions, vegetables

or even cereals, the rate of inflation tends to be

extremely high, pointing to the role of speculation

in driving prices in the short run. Finally, even

when such influences are not at work, there seem to

be factors operative that keep the ''all commodities''

inflation rate high.

Even though it is still early to say, the trend over

the last one-and-a-half years suggest that there are

structural factors at work that are setting a higher

floor to the inflation rate. They may be neutralised

in the future. But even if they are, they could as

well return to play a role subsequently. The government

has recognised this structural, inflationary tendency

in a peculiar, in fact patently absurd, way. It attributes

the inflation to the demand-side effects of high growth.

If people are richer because of an 8-9 per cent growth

rate, they are bound to demand more. Since supply

does not adjust, prices are bound to rise.

There are many assumptions here. That when GDP grows,

those who need to buy and consume more cereals, pulses

and vegetables garner a reasonable share of the benefits

of that growth. Or that when GDP grows, such growth

cannot occur in large measure in the commodity producing

sectors, resulting in a widening gap between the demand

for and supply of certain goods. That even though

the ''high growth'' era began in 2004, it is only

now that it has generated demand-supply imbalances.

And, that if there is indeed a supply-demand imbalance

the government is unable, for whatever reason, to

redress it by resorting to imports. Making such assumptions

is not just wishful thinking, but avoiding the conundrum.

It is not that there are no demand-supply imbalances.

India's growth has indeed been lopsided. As has been

argued by perceptive analysts, India's high GDP growth

was recorded in a period when the agricultural sector

and a range of petty producers were experiencing a

crisis, an aspect of which was the non-viability of

crop production and therefore an extremely slow growth

of agricultural output and GDP. At some point, that

long-term crisis was likely to result in an unsustainable

demand-supply imbalance.

But there are two other factors that are structurally

embedded in the economic environment generated by

the government's neoliberal reform agenda adopted

for two decades now. The first is a tendency where

corporate consolidation in production and trade, decontrol

that permits profiteering, a reduced role for public

agencies and public sector firms and the withdrawal

or curtailments of subsidies on a range of inputs,

has pushed up costs and prices (including administered

prices) substantially. As some have argued, India

is increasingly a high input price and high output

price economy, with a rising floor for many prices.

The second is the role that speculation has to come

to play, with liberalised trade, with the presence

of large corporate players in the wholesale and retail

trade and with the growing role of futures and derivatives

trading in a host of commodities. Add the influence

of these two factors to the underlying crisis in some

commodity producing sectors and the long-term, structural

inflation is more than partly explained.

The government of course does not consider these angles

worth pursuing. The reason is partly ideological.

It cannot bear questioning the outcome of reform.

It cannot bear suggesting that corporate entry can

lead to profiteering in a context of decontrol. It

does not believe that speculation in futures markets

can push up spot prices, and has banned some of these

markets only because of public pressure. It cannot

contemplate a larger role for the state and no role

for corporate (domestic and foreign) players in the

both wholesale and retail trade. In the event, all

that the Prime Minister's emergency meetings on the

inflation issue could throw up is an inter-Ministerial

group mandated to monitor short-term fire-fighting

measures and promote actions that the government has

claimed to be promoting for many years now.

To top it all, precisely at a time when it can come

in handy, the government is threatening to renege

on the UPA's promise to deliver universal access to

a minimum quota of food through the public distribution

system. Riding on the argument that not enough foodgrain

is available, even though production has been good,

stocks with the government are comfortable and foreign

exchange that can be used to import even more is being

handed over to the rich to be transferred to accounts

abroad, it has used the Prime Minister's Economic

Advisory Council to stall even a diluted proposal

from the Sonia Gandhi-led National Advisory Council

to expand the public distribution system. No guesses

are needed to identify where the push for this effort

to kill the proposal comes from. And here too the

ultimate source is the neoliberal ideology that wants

to cut expenditures and reduce a fiscal deficit even

as tax concessions are being handed out to the well-to-do.

The government is not alone in all this. There is

an influential body of opinion, including in the mainstream

media that the inflation problem is the result of

poor supply management that cannot, at low cost, mobilise

and reach supplies from wherever it is available to

wherever it is needed. This creates unnecessary shortages

that push up prices as well as encourages speculation

that aggravates the price increase. The solution therefore

is corporate retailing services, including that which

would be offered by large transnational retail firms.

According to reports (The Hindu, January 19. 2011),

using inflation as the excuse, the cabinet is about

to consider a controversial proposal to permit 51

per cent foreign equity in multi-brand retailing.

This argument too borders on the absurd. It ignores

the fact that, though India has till quite recently

had no such retail trade structure, there have been

long periods when prices and inflation have been kept

in control. It also ignores the evidence from other

contexts which shows that where such retail chains

are active, the margin between prices paid to producers

and charged to consumers tends to be high, buoyant

and downward sticky.

Neoliberal thinking not only leads to policy paralysis

and absurd reasoning. It also results in policy responses

that are contrary to what is needed. Thus, in the

midst of the current inflationary mess, on the basis

of the liberalised pricing mechanism, the oil companies

have been allowed to hike the prices of petrol a second

time in quick succession. Given the role of public

sector firms here, nobody would believe that a nod

from the government was not obtained before the hike.

If balance has to be maintained a diesel hike must

follow. This government may go in for that as well.

Doing this to the prices of what are universal intermediates

in the midst of an inflation emergency might be seen

by some as madness. If the belief that the people

can be called upon to sacrifice real incomes because

reform cannot be held back or reversed is a sign of

madness, then possibly it is.