Themes > Current Issues

26.07.2008

A Long View of Global GDP Growth

Jayati

Ghosh

Discussions

of GDP growth at both national and international levels often get carried

away by relatively recent trends. But it is sometime useful to situate

recent income growth in the longer term context, if only to remind ourselves

of the structural processes involved.

It is also useful because the second half of the twentieth century is generally perceived as the most dynamic in the history of capitalism. It is also seen as a period in which at least some developing countries managed to improve their relative position in the global income hierarchy, in different phases and through different trajectories.

There are various ways in which this is supposed to have occurred. Import substituting industrialisation in the 1950s and 1960s played a role in diversifying large developing and thereby generating a higher rate of GDP growth. Oil exporting countries benefited from the oil price increases of the second half of the 1970s, which enabled some of them top move to a higher level of per capita income. According to some analysts, the most recent "globalisation" phase of the 1990s has enabled some countries – China and India in particular – to benefit from more open global trade and thereby increase per capita incomes and reduce poverty.

All this would presumably have operated to create more convergence of incomes between the developed and developing worlds, even if in fits and starts, such that the gap between per capita incomes of countries across the world would start reducing. While this can and has been examined with econometric analyses of varying degrees of sophistication, it is also possible to just look at the overall evidence on GDP growth patterns from different sources.

Table 1 provides evidence on shares of various regions over the period 1950-1998, of global population and global GDP re-estimated according to Purchasing Power Parity (PPP). These are based on data provided in an OECD study by Angus Maddison (Angus Maddison: The World Economy: A Millenial Perspective, OECD Paris 2001).

PPP estimates are used instead of nominal exchange rates to compare income across economies, because of the widely observed reality that currencies command different purchasing power in different countries, than is suggested by the nominal rates. However, there are some well-known problems in the estimates of income using exchange rates based on PPP, not least of which are the issues of choosing comparable baskets of goods and the poor quality of the data on actual prices prevailing in different countries (including large developing countries such as China and India) that are used in such studies, which affect the reliability of such calculations.

There is a less talked about but equally significant conceptual problem with using PPP estimates. In general, countries that have high PPP, that is where the actual purchasing power of the currency is deemed to be much higher than the nominal value, are typically low-income countries with low average wages. It is precisely because there is a significant section of the workforce that receives very low remuneration, that goods and services are available cheaply. Therefore, using PPP-modified GDP data may miss the point, by seeing as an advantage the very feature that reflects greater poverty of the majority of wage earners in that economy.

Nevertheless, PPP-based estimates have been widely used, even though they are likely to overestimate incomes of working people in lower-income countries for the reasons described above. Maddison's estimates, presented in Table 1, allow us to track the relative population and income shares by broad category of country for the latter half of the 20th century.

It is evident that, as far as the countries that were known as "developed" in 1950 are concerned, there has been relatively little change in the per capita income position vis-a-vis the rest of the world, especially since the mid-1970s. In 1950 the developed countries received nearly 60 per cent of global income, but they also accounted for almost 20 per cent of world population. In the twenty five years after 1973, the share of the income of the developed countries fell by only 10 per cent, or 5.3 percentage points, whereas the share of population declined by 22 per cent or 3.5 percentage points. So even in PPP terms, just above one-tenth of global population in the developed countries still receives nearly half the world's income.

Consider the same ratios for the developing countries taken as a group. This category includes all the “success stories” of the developing world in East Asia and elsewhere, the socialist countries outside of Eastern Europe and the former USSR as well as several oil-exporting countries that have benefited from global oil price booms. There has been some improvement in global income shares for this group as a whole, but this has been far outpaced by the growing share of the developing world in global population. So, between 1950 and 1998 developing countries managed to increase their share of global income by 15 per cent, or nearly 11 percentage points, their share of global population increased by a whopping 63 per cent, or 19 percentage points, so that there was no relative increase in per capita terms.

The countries of the former Soviet Union and Eastern Europe have typically been treated as outside of both these categories, and it is interesting to note how this process worked out for these countries. Between 1950 and 1973, the conditions appeared broadly stable, that is, there was a slight decline in both population and global GDP shares. However, after 1973 – or more accurately, probably after 1989 and the collapse of the Berlin Wall – there has been a sharp decline in population share (35 per cent, or 4 percentage points), associated with an even sharper decline in income share (59 per cent, or 8 percentage points).

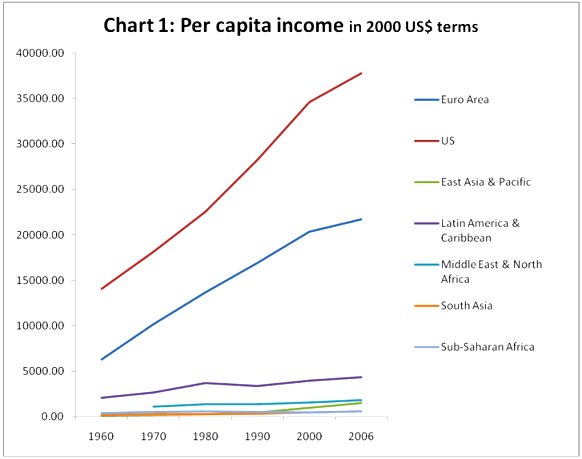

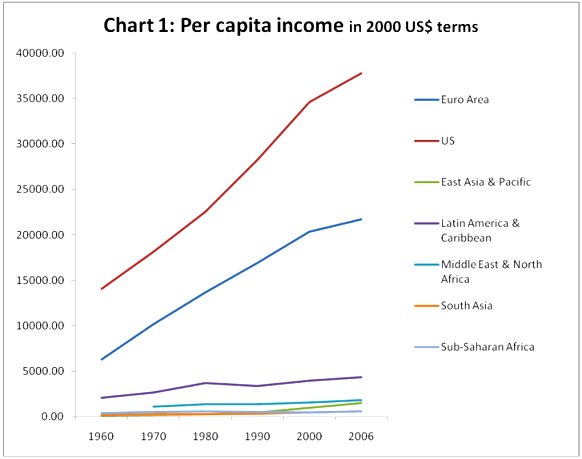

Given all the problems of basing inter-country income comparisons on PPP estimates, it is worth looking at comparisons based on nominal exchange rates, which do provide some idea of inter-country income differentials especially in a world in which trade penetration is increasing. Chart 1 provides the evidence on per capita incomes across some major countries and country groupings for the period 1960-2006, based on the World Bank’s World Development Indicators.

This chart shows very clearly how large the global income gaps are. The initial differences in per capita incomes (in 1960 in this case) were so large that even quite rapid increases in per capita incomes in some regions over the subsequent four and half decades have not managed to make the gap more repsectable. Thus, while the per capita income of the fastest growing developing region – East Asia – increased by more than ten times over this period compared to an increase of less than three times for the US, in 2006, the average income for US was still fifteen times that of East Asia.

For other developing regions the per capita income gaps have been even larger and in some cases growing. Thus, the per capita GDP in the current Euro area in 1960 was 34 times that of South Asia; but by 2006, it had increased to 36 times. For Sub-Saharan Africa, the widening gap was even more stark. In 1960, the per capita income of the countries that are now in the Euro Area was 15 times that of Sub-Saharan Africa; by 2006, the difference was as large as 38 times.

Latin America was then and remains the richest developing region, yet the per capita income gaps between it and both the US and the EU have increased in the past forty six years. Even for countries in the Middle East and North Africa, which contains several major oil exporters, the income gaps have grown substantially with respect to both the US and the Euro Area countries.

Another way of examining this is to look at the share of countries or regions in world GDP in dollar terms, rather than in PPP terms. It turns out that at nominal exchange rates, the share of developing countries, even the largest and most dynamic ones, remains quite puny. Even in the first six years of this century, after more than two decades of rapid growth in China and India, the two countries account for less than 7 per cent of global GDP compared to 30 per cent for the US (changed relatively little from the 1960s) and 14 per cent for Japan. The share of China, India, Brazil and Argentina together in 2000-06 was less than 10 per cent.

This pattern is at least partly because the growth performance of the developing world has been so uneven. Within the developing world, only East Asia and the Pacific and South Asia show any significant acceleration of growth since the 1960s or indeed higher growth rates than the developing world. Furthermore, it is evident that for South Asia the acceleration is relatively recent, so it is really only East Asia and the Pacific that in the aggregate has shown rapid growth over a prolonged period.

The other developing regions showed higher growth rates during the import substitution phase, and do not appear to have benefited much from the "globalisation" phase in GDP growth terms. If the 1980s was a "lost decade" for Latin America, with declines in real GDP, the subsequent decade was not much better, especially given the low base. Even the recent spurt has led to average growth rates of less than 2 per cent per annum. Meanwhile Sub-Saharan Africa has experienced two lost decades, with average real GDP (in aggregate, not per capita terms) falling continuously in the 1980s and the 1990s.

So the picture of a very dynamic and rapidly changing world economy, in which developing countries are emerging as the major players, may be overplayed. A longer term perspective on growth suggests that for much of the developing world, relative positions in the international economy have hardly changed at all.

It is also useful because the second half of the twentieth century is generally perceived as the most dynamic in the history of capitalism. It is also seen as a period in which at least some developing countries managed to improve their relative position in the global income hierarchy, in different phases and through different trajectories.

There are various ways in which this is supposed to have occurred. Import substituting industrialisation in the 1950s and 1960s played a role in diversifying large developing and thereby generating a higher rate of GDP growth. Oil exporting countries benefited from the oil price increases of the second half of the 1970s, which enabled some of them top move to a higher level of per capita income. According to some analysts, the most recent "globalisation" phase of the 1990s has enabled some countries – China and India in particular – to benefit from more open global trade and thereby increase per capita incomes and reduce poverty.

All this would presumably have operated to create more convergence of incomes between the developed and developing worlds, even if in fits and starts, such that the gap between per capita incomes of countries across the world would start reducing. While this can and has been examined with econometric analyses of varying degrees of sophistication, it is also possible to just look at the overall evidence on GDP growth patterns from different sources.

Table 1 provides evidence on shares of various regions over the period 1950-1998, of global population and global GDP re-estimated according to Purchasing Power Parity (PPP). These are based on data provided in an OECD study by Angus Maddison (Angus Maddison: The World Economy: A Millenial Perspective, OECD Paris 2001).

PPP estimates are used instead of nominal exchange rates to compare income across economies, because of the widely observed reality that currencies command different purchasing power in different countries, than is suggested by the nominal rates. However, there are some well-known problems in the estimates of income using exchange rates based on PPP, not least of which are the issues of choosing comparable baskets of goods and the poor quality of the data on actual prices prevailing in different countries (including large developing countries such as China and India) that are used in such studies, which affect the reliability of such calculations.

There is a less talked about but equally significant conceptual problem with using PPP estimates. In general, countries that have high PPP, that is where the actual purchasing power of the currency is deemed to be much higher than the nominal value, are typically low-income countries with low average wages. It is precisely because there is a significant section of the workforce that receives very low remuneration, that goods and services are available cheaply. Therefore, using PPP-modified GDP data may miss the point, by seeing as an advantage the very feature that reflects greater poverty of the majority of wage earners in that economy.

Nevertheless, PPP-based estimates have been widely used, even though they are likely to overestimate incomes of working people in lower-income countries for the reasons described above. Maddison's estimates, presented in Table 1, allow us to track the relative population and income shares by broad category of country for the latter half of the 20th century.

Table

1: Shares

of global population and income in PPP terms |

||

|

Percent share of world population |

Per cent share of world output in PPP terms |

|

|

Developed Countries |

||

|

1950 |

19 |

57 |

|

1973 |

15.6 |

50.9 |

|

1998 |

12.1 |

45.6 |

|

Developing Countries |

||

|

1950 |

70.4 |

30 |

|

1973 |

75.2 |

36.1 |

|

1998 |

81 |

49 |

|

Eastern Europe and Former USSR |

||

|

1950 |

10.6 |

13.1 |

|

1973 |

9.2 |

12.8 |

|

1998 |

6.9 |

5.4 |

|

Source: Angus Maddison (2001) |

||

It is evident that, as far as the countries that were known as "developed" in 1950 are concerned, there has been relatively little change in the per capita income position vis-a-vis the rest of the world, especially since the mid-1970s. In 1950 the developed countries received nearly 60 per cent of global income, but they also accounted for almost 20 per cent of world population. In the twenty five years after 1973, the share of the income of the developed countries fell by only 10 per cent, or 5.3 percentage points, whereas the share of population declined by 22 per cent or 3.5 percentage points. So even in PPP terms, just above one-tenth of global population in the developed countries still receives nearly half the world's income.

Consider the same ratios for the developing countries taken as a group. This category includes all the “success stories” of the developing world in East Asia and elsewhere, the socialist countries outside of Eastern Europe and the former USSR as well as several oil-exporting countries that have benefited from global oil price booms. There has been some improvement in global income shares for this group as a whole, but this has been far outpaced by the growing share of the developing world in global population. So, between 1950 and 1998 developing countries managed to increase their share of global income by 15 per cent, or nearly 11 percentage points, their share of global population increased by a whopping 63 per cent, or 19 percentage points, so that there was no relative increase in per capita terms.

The countries of the former Soviet Union and Eastern Europe have typically been treated as outside of both these categories, and it is interesting to note how this process worked out for these countries. Between 1950 and 1973, the conditions appeared broadly stable, that is, there was a slight decline in both population and global GDP shares. However, after 1973 – or more accurately, probably after 1989 and the collapse of the Berlin Wall – there has been a sharp decline in population share (35 per cent, or 4 percentage points), associated with an even sharper decline in income share (59 per cent, or 8 percentage points).

Given all the problems of basing inter-country income comparisons on PPP estimates, it is worth looking at comparisons based on nominal exchange rates, which do provide some idea of inter-country income differentials especially in a world in which trade penetration is increasing. Chart 1 provides the evidence on per capita incomes across some major countries and country groupings for the period 1960-2006, based on the World Bank’s World Development Indicators.

This chart shows very clearly how large the global income gaps are. The initial differences in per capita incomes (in 1960 in this case) were so large that even quite rapid increases in per capita incomes in some regions over the subsequent four and half decades have not managed to make the gap more repsectable. Thus, while the per capita income of the fastest growing developing region – East Asia – increased by more than ten times over this period compared to an increase of less than three times for the US, in 2006, the average income for US was still fifteen times that of East Asia.

For other developing regions the per capita income gaps have been even larger and in some cases growing. Thus, the per capita GDP in the current Euro area in 1960 was 34 times that of South Asia; but by 2006, it had increased to 36 times. For Sub-Saharan Africa, the widening gap was even more stark. In 1960, the per capita income of the countries that are now in the Euro Area was 15 times that of Sub-Saharan Africa; by 2006, the difference was as large as 38 times.

Latin America was then and remains the richest developing region, yet the per capita income gaps between it and both the US and the EU have increased in the past forty six years. Even for countries in the Middle East and North Africa, which contains several major oil exporters, the income gaps have grown substantially with respect to both the US and the Euro Area countries.

Another way of examining this is to look at the share of countries or regions in world GDP in dollar terms, rather than in PPP terms. It turns out that at nominal exchange rates, the share of developing countries, even the largest and most dynamic ones, remains quite puny. Even in the first six years of this century, after more than two decades of rapid growth in China and India, the two countries account for less than 7 per cent of global GDP compared to 30 per cent for the US (changed relatively little from the 1960s) and 14 per cent for Japan. The share of China, India, Brazil and Argentina together in 2000-06 was less than 10 per cent.

This pattern is at least partly because the growth performance of the developing world has been so uneven. Within the developing world, only East Asia and the Pacific and South Asia show any significant acceleration of growth since the 1960s or indeed higher growth rates than the developing world. Furthermore, it is evident that for South Asia the acceleration is relatively recent, so it is really only East Asia and the Pacific that in the aggregate has shown rapid growth over a prolonged period.

The other developing regions showed higher growth rates during the import substitution phase, and do not appear to have benefited much from the "globalisation" phase in GDP growth terms. If the 1980s was a "lost decade" for Latin America, with declines in real GDP, the subsequent decade was not much better, especially given the low base. Even the recent spurt has led to average growth rates of less than 2 per cent per annum. Meanwhile Sub-Saharan Africa has experienced two lost decades, with average real GDP (in aggregate, not per capita terms) falling continuously in the 1980s and the 1990s.

So the picture of a very dynamic and rapidly changing world economy, in which developing countries are emerging as the major players, may be overplayed. A longer term perspective on growth suggests that for much of the developing world, relative positions in the international economy have hardly changed at all.

© MACROSCAN 2008