Global Oil Prices*

There

was a time when global oil prices reflected changes in real demand

and supply of crude petroleum. Of course, as with many other primary

commodities, the changes in the market could be volatile, and so

prices also fluctuated, sometimes sharply. More than any other commodity,

the global oil market was seen to reflect not only current economic

conditions and perceptions of future activity, but also geopolitical

changes and cross-currents.

Ever since the early 1970s, when group of some major oil exporting

countries OPEC, forced a three-fold increase in global oil prices

its shadow has loomed large. There is still widespread perception

that the cartel of oil-exporting countries can manipulate and influence

the price by changing the level of their own supplies. As a result,

even oil-exporting countries that are not members of the cartel

have benefited from OPEC's decisions about supply, since they have

also been beneficiaries of rising oil prices.

But in fact, OPEC is more like a club of a minority of oil producers,

rather than a cartel that is in command of world oil supply. It

controls less than 40 per cent of world oil production, compared

to 70 per cent in the early 1970s. Non-OPEC countries account for

increasingly significant proportions of global supply: Russia has

overtaken Saudi Arabia as the largest supplier of crude oil since

2009. Partly as a result of this, OPEC has recently been quite inefficient

in imposing any kind of production quota on its members, who have

happily increased or decreased their production as they wished.

Most of its members are producing exactly as they would if OPEC

did not exist.

Indeed, for the past two decades, OPEC's role has generally been

more towards price stabilisation rather than pushing for increases,

and it may even have played a moderating role in oil markets, including

when particular events such as political disruptions in major exporting

countries caused sudden supply shortfalls. OPEC formerly abandoned

its declared price band in 2005, and since then has been largely

powerless in determining prices.

The argument that rising demand from China and India has determined

the upward trend in global oil prices is also unjustified. While

these two countries (and particularly China) do account for growing

(but still small) shares of global demand, these increases have

been counterbalanced from slower demand from other regions of the

world, including the US and Europe. As a consequence, on average,

global oil demand has continued to grow at between 1 and 2 per cent

per annum over the past five years, usually at a rate slightly below

the annual rate of increase in global oil production.

Recent price changes in global oil markets are increasingly affected

by other forces, which have more to do with financial speculation

and expectations than with current movements in demand and supply.

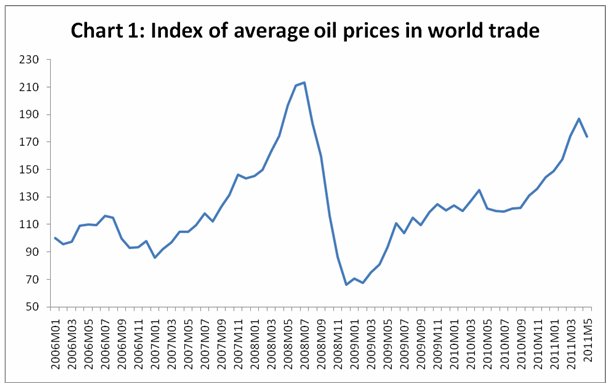

Chart 1 indicates the extent of the recent rise, and shows how much

it mirrors the earlier rise in oil prices between January 2007 and

June 2008.

This confirms the points made earlier about the role of other factors

in global oil markets. Clearly, this extent of price volatility

– with dramatic rise, fall and rise again within the space of three

years - cannot be the result of real demand and supply changes.

Despite this, most mainstream media persist in trying to isolate

some factors affecting production in particular locations, to account

for the price changes.

The ongoing crisis in the Middle East – and particularly Libya –

is generally believed to be the impetus behind the latest spurt

in prices. But Libya produces less than 3 per cent of global petroleum

output, and Saudi Arabia (whose current excess stocks are already

more than annual production in Libya and Algeria) has already made

up current shortfalls and promised to compensate for any future

shortfall. Since the unrest in the Arab region began, there has

been no significant change in global oil production, which continues

to average around 88 million barrels per day.

In any case, currently global spare oil capacity is closer to historic

highs than to historic lows. Proven reserves of oil amount to more

than 40 years worth of global consumption at current levels – the

highest such ratio in the past thirty years.

The current price spike is therefore not the result of demand and

supply imbalances but is driven by uncertainty, rumour and speculative

financial activity in oil futures markets. Even in terms of expectations,

Libya is only part of the problem (and in fact oil production still

continues in many Libyan facilities despite the civil war). The

concern in financial markets may be more about the potential endgame

if the unrest spreads to Saudi Arabia. But the increase in oil prices

is happening well before such a drama actually plays out, and before

any serious disruption to global supply.

It is therefore likely that the rapid increases in oil price and

the associated price volatility over the past year in particular,

are largely driven by purely financial activity. This is very similar

to the effects of financial speculation on other commodity markets

such as food items. The volume of trading in crude oil futures contracts

has expanded dramatically over the past decade. As noted by Robert

Pollin and James Heintz (''How speculation is affecting gasoline

prices today'', Americans for Financial Reform mimeo, July 2011),

the overall level of futures market trading of crude oil contracts

on the New York Mercantile Exchange is currently 400 percent greater

than it was in 2001, and 60 percent higher than it was two years

ago. Even relative to the increases in the physical production of

global oil supplies, trading is still 300 percent greater today

than it was in 2001, and 33 percent greater than two years previously.

The ratio of ''open interest'' contracts of NYMEX (New York Metals

Exchange) crude oil futures to total global oil production is one

useful indicator of the growing extent of speculative activity in

this market. This ratio was between 4-6 per cent in the first half

of the 2000s, increased to 12 per cent in late 2006 and then to

as much as 18 per cent just before the oil price peaked in June

2008. It then fell to 13 per cent in the middle of 2008, as oil

prices fell. It has been mostly rising since then, with average

levels of 16 per cent in the past few months. Large traders in particular

show growing volumes of ''long'' positions that anticipate future

price increases. (Data from Commodity Futures Trading Commission

website www.cftc.gov

accessed 6 July 2011).

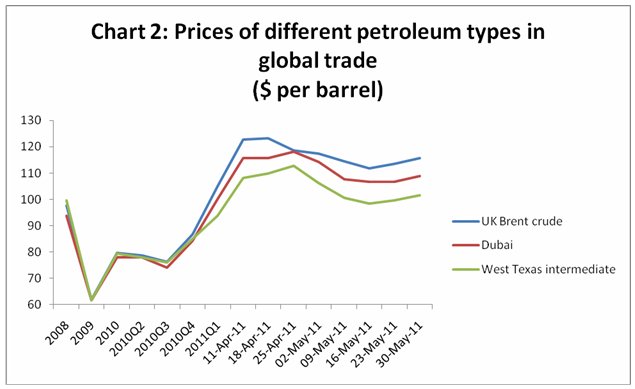

While this explains some of the recent volatility witnessed in oil

prices, there are some other more puzzling features of the recent

price increases. Earlier, the three major forms of crude petroleum

in the global market – Brent Crude, West Texas Intermediate and

Dubai crude – generally showed similar if not identical prices.

If anything, the price of West Texas Intermediate oil used to be

slightly higher because of perceived better quality and lower sulphur

content.

However, in the very recent past the prices have diverged, and as

Chart 2 shows, West Texas Intermediate is now the lowest of the

three prices. By the middle of June the difference was more than

$22 per barrel. It is not fully clear what is causing this deviation,

especially the increasing extent of it. But it is also true that

futures market activity is greater for both Brent and Dubai crude

oil.

We

all know who loses from rising oil prices: most of us. Oil prices

directly and indirectly enter into all other prices, through higher

fuel costs of production and transport. Agriculture is directly

affected, so food prices will definitely rise further with this

oil price increase, worsening the resurgent food crisis. Such cost

pressures have another consequence: they push governments to inflation

control measures, such as higher interest rates. In many countries

this worsens the chances for the already fragile economic recovery

after the crisis. So people across the world face lower real incomes

and may face reduced employment opportunities.

Oil-importing developing countries tend to get hit much worse than

other oil importers. First, the energy-intensity of output is still

much higher (twice on average) than production in OECD countries.

Second, developing countries are often more foreign exchange-constrained

and so high oil import bills lead to balance of payments difficulties.

The poorest countries are usually the worst affected, and within

developing countries poorer groups take the brunt of the impact

in higher costs of living and lower wage prospects.

So the doubling of the oil price that we have seen in the past year

has already destroyed any positive effects of foreign aid that oil-importing

developing countries receive. Since it is also linked to global

food prices the negative effects are compounded for food importing

countries. During the last such price peak in 2008, there were calls

for compensatory financing to be provided to oil and food importers

by the IMF. This never came about, but this time round we have not

even heard such noises, certainly not loudly enough.

Who gains from the rising oil prices? The conventional approach

is to look at the countries that are major oil exporters, and somehow

assume that they are the beneficiaries of such price spikes, and

that this leads to a redistribution of global income away from oil-importing

to oil-exporting countries. This approach is reinforced by the media,

which keeps emphasising the windfall gains of governments in oil

exporting countries.

But this misses the point. The really big gainers – accounting for

the largest portion of the gains by far – are the big oil companies.

In fact, big oil, which suffered a setback during the Great Recession,

is back with a bang, riding on the back of the recovery in petroleum

prices in 2010. The major oil companies that announced their results

in January 2011 reported a doubling of profits in 2010 compared

to the previous year. The three big US companies ExxonMobil, Chevron

and ConocoPhillips together had nearly $60 billion profits after

all costs and taxes. The profits of the Anglo-Dutch company Royal

Dutch Shell also doubled, even though production was lower than

expected.

Why do profits of big oil companies increase so much during periods

of high or rising oil prices? Basically, the costs per barrel of

the companies reflect their historical costs of drilling, exploration

and/or purchase of crude oil, which often have little or nothing

to do with current crude prices. But they are quick to pass on current

crude oil prices to consumers in the form of higher prices for their

products. By contrast, they tend to be much more lethargic about

passing on lower crude prices in the form of lower prices of processed

oil. So increases in crude oil prices lead to enormous windfall

gains for these companies.

In the current price surge, therefore, the real (and maybe only)

gainers are financial speculators in oil futures markets and the

big oil companies that can pass on much more than their own costs

in the form of much higher prices due to the general sense of frenzy

in oil markets. So the case for immediate and substantial taxes

on the windfall oil profits of multinational companies is very compelling.

And so is the case for much more far-reaching and effective regulation

and control of the speculative activity in oil futures and other

commodity markets that is currently causing so much collateral damage.

*This article was originally published in

the Frontline, Vol.: 28, No. 15, July 16-29, 2011.