Themes > Current Issues

03.03.2004

Capital Account Convertibility: Opening the sluice gates

On

February 4, the Reserve Bank of India took a major step

forward towards full convertibility of the rupee. It

announced that resident Indians can, with immediate

effect, remit an amount of up to $25,000 per calendar

year for any current or capital account transaction, or

a combination of both. This implies that resident

Indians would not just be able to open and operate

foreign currency accounts outside India, but can use the

money remitted to those accounts to acquire financial or

immovable assets without prior approval from the RBI.

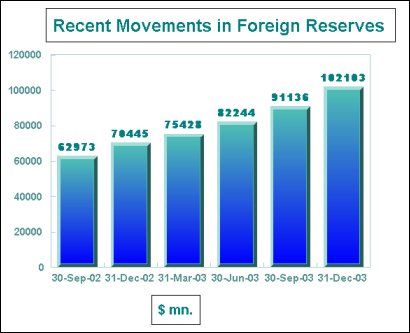

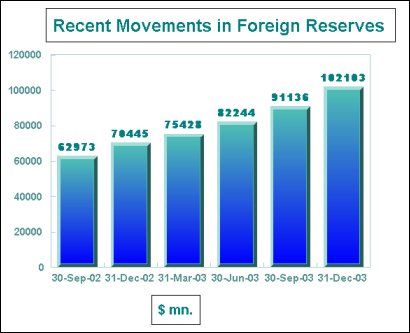

On the surface, the sum of $25,000 involved may appear small, especially when compared to net capital inflows into the country of $12 billion in 2002-03 and $6 billion in the first quarter (April-June) of 2003-04, and reserve accumulation of $17 billion during 2002-03, and around 25 billion during April to December 2003. But, looked at otherwise, if one million Indians, or just 0.1 per cent of the country's population choose to avail of the facility in full, the outflow would be adequate to wipe out the foreign exchange reserves accumulated during the first three quarters of a year (2003-04) that has seen record inflows of capital. It is not India's new and old rich alone who would seek to exploit the new ‘facility'. The large numbers of middle class households who have members moving abroad on H1 B visas or for educational purposes would see some reason for holding an account, if not making some investment, abroad. A million may not be a large figure for the number willing every year to transfer the equivalent of Rs. 11.5 lakh abroad at current exchange rates. Not surprisingly, within a day after the new facility was announced, banks have rushed to press, to advertise their willingness to manage remittances under this head for interested clients.

Needless to say, if all or a large part of capital inflows are consumed in this fashion, it could send out a signal that the country is losing its ability to meet its repatriation commitments, either in the form of the returns that would accrue to foreign investors or in the form of permission to exit from investments in the country. This could slow capital inflows or even result in outflows, leading to a collapse in reserves and a financial crisis. This is typically the way in which countries that are temporarily the favourites of foreign investors and experience a capital inflow surge often find themselves the victims of outflows that lead to crisis. The "feast-or-famine" syndrome characteristic of capital flows to emerging markets has been documented widely. A reading of that literature does warrant the conclusion that by beginning the journey to full convertibility, the government has opened the sluice gates to outflows that can empty its foreign exchange reserves.

An analysis of the sources of reserve accumulation by the RBI over a long period points to the important role of inflows in the form of NRI deposits and foreign institutional investor investments. Outstanding NRI deposits increased from US$ 13.7 billion at end-March 1991 to US$ 31.3 billion at end-September 2003. Cumulative net FII investments, increased from US$ 827 million at end-December 1993 to US$ 19.2 billion at end-September 2003. These kinds of investments rarely, if ever at all, finance new investments in the domestic economy. These are also typically inflows that would be reversed in case of any sign of uncertainty.

Thus, comparisons of likely outflows with the size of inflows and the extent of reserve accumulation are not without some basis. Reserve accumulation occurs when the RBI is forced to intervene in the foreign currency market and purchase dollars or other foreign currencies. This it is forced to do when large capital inflows result in a surplus of foreign exchange in the system, since the supply of foreign exchange exceeds demand from firms and individuals for permitted current and capital account transactions such as imports, private or business travel, remittance for gifts, donations, study abroad, medical treatment, investment abroad and so on. When the supply of foreign exchange exceeds such demand, the rupee tends to appreciate vis-ŕ-vis foreign currencies under India's liberalized and market-driven exchange rate regime. A rising rupee increases the dollar value of India's exportables and adversely affects her export competitiveness. It is to prevent such appreciation that the RBI has been purchasing foreign exchange in the market and enhancing its reserves.

Beyond a point, however, increasing reserves are a problem for the central bank. When the foreign exchange assets of the RBI rise, so do its liabilities, which typically imply an increase in money supply. Since allowing that to happen amounts to loosing control of its monetary policy lever, the central bank chooses to retrench other assets such as government securities to sterilize inflows.

Unfortunately for the Reserve Bank of India, foreign capital inflows have in recent months been massive and unrelenting. The consequent huge and rapid increase in its reserves, can no more be sterilized easily, since the central bank has already brought down its holding of government securities substantially.

Excessive reserve accumulation is a problem also because of its negative balance of payments implications. Investors bringing in the capital earn minimum returns of around 7 percent. The maximum would be many multiples of that, especially from capital gains associated with recent investments in the stock market. These returns have to be paid out in foreign exchange. On the other hand, when the dollar flowing into the country are acquired by the RBI and invested through central and commercial banks, the returns are much lower. According to the RBI, during the year 2002-03 (July-June), the return on foreign currency assets, excluding capital gains less depreciation, decreased to 2.8 per cent from 4.1 per cent during 2001-02, because of lower international interest rates. This implies that the interest associated with capital inflow and its accretion as reserves involves little foreign exchange earning but substantial foreign exchange payouts.

Finally, it is becoming diplomatically increasingly difficult to accumulate reserves in order to prevent currency appreciation. India has been identified along with China as a country whose large reserves prove that it has an "undervalued" currency that discriminates against imports from the US. The pressure to allow the currency to appreciate is therefore on the increase.

For all these reasons, it had become clear to the central bank and the government that something had to be done to prevent further rapid reserve accumulation. The choice, therefore, was either to curb flows or to stimulate the demand for foreign exchange. Given its unthinking commitment to liberalization and "reform", it's the latter route that the government has chosen.

Recent months have, therefore, seen not just irrational and sometimes bizarre trade liberalisation manoeuvres, such as across-the-board duty reductions and the license to bring in laptops duty free as part of baggage, but the relaxation of ceilings on remittances abroad for purposes as varied as education, health and investment. All of these have proved inadequate given the fact that India has proved to be the flavour of the season for foreign investors, who have rushed into the country in herd-like fashion.

It is this set of circumstances, rather than rational decision-making, that has forced the government to all on a sudden liberalize controls on capital account outflows. The sequence has to be noted. First, regulations regarding purely financial inflows are liberalized to attract capital into the country so as to finance the outflows that trade liberalization was expected to result in. Since the initial response of foreign investors was lukewarm, further liberalization, in the form of relaxing ceilings on FII holdings of equity in firms in different sectors, was resorted to. Suddenly, for reasons extraneous to the performance of the Indian economy, which has grown at an indifferent rate for at least three consecutive years before the current "recovery", inflows accelerate. Unable to manage those inflows, the government attempts to encourage foreign exchange profligacy through liberalization of foreign exchange access for various current account transactions. When even that proves inadequate, it opts for capital account convertibility.

The problem is that when controls on capital account outflows are liberalized, it is difficult to control the volume of outflows. And if large outflows raise the threat of depreciation in the value of the rupee, outflows accelerate and capital flight out of rupee denominated assets would occur. Having whetted the appetite of India's rich for a financial foothold abroad, it would be extremely difficult to reverse the decision. Moreover, any such reversal would encourage the flight of financial investors out of the country. A currency and financial collapse would be inevitable. In short, the sluice gates have been opened. It is, therefore, clearly time to prepare for the coming crisis.

On the surface, the sum of $25,000 involved may appear small, especially when compared to net capital inflows into the country of $12 billion in 2002-03 and $6 billion in the first quarter (April-June) of 2003-04, and reserve accumulation of $17 billion during 2002-03, and around 25 billion during April to December 2003. But, looked at otherwise, if one million Indians, or just 0.1 per cent of the country's population choose to avail of the facility in full, the outflow would be adequate to wipe out the foreign exchange reserves accumulated during the first three quarters of a year (2003-04) that has seen record inflows of capital. It is not India's new and old rich alone who would seek to exploit the new ‘facility'. The large numbers of middle class households who have members moving abroad on H1 B visas or for educational purposes would see some reason for holding an account, if not making some investment, abroad. A million may not be a large figure for the number willing every year to transfer the equivalent of Rs. 11.5 lakh abroad at current exchange rates. Not surprisingly, within a day after the new facility was announced, banks have rushed to press, to advertise their willingness to manage remittances under this head for interested clients.

Needless to say, if all or a large part of capital inflows are consumed in this fashion, it could send out a signal that the country is losing its ability to meet its repatriation commitments, either in the form of the returns that would accrue to foreign investors or in the form of permission to exit from investments in the country. This could slow capital inflows or even result in outflows, leading to a collapse in reserves and a financial crisis. This is typically the way in which countries that are temporarily the favourites of foreign investors and experience a capital inflow surge often find themselves the victims of outflows that lead to crisis. The "feast-or-famine" syndrome characteristic of capital flows to emerging markets has been documented widely. A reading of that literature does warrant the conclusion that by beginning the journey to full convertibility, the government has opened the sluice gates to outflows that can empty its foreign exchange reserves.

An analysis of the sources of reserve accumulation by the RBI over a long period points to the important role of inflows in the form of NRI deposits and foreign institutional investor investments. Outstanding NRI deposits increased from US$ 13.7 billion at end-March 1991 to US$ 31.3 billion at end-September 2003. Cumulative net FII investments, increased from US$ 827 million at end-December 1993 to US$ 19.2 billion at end-September 2003. These kinds of investments rarely, if ever at all, finance new investments in the domestic economy. These are also typically inflows that would be reversed in case of any sign of uncertainty.

Thus, comparisons of likely outflows with the size of inflows and the extent of reserve accumulation are not without some basis. Reserve accumulation occurs when the RBI is forced to intervene in the foreign currency market and purchase dollars or other foreign currencies. This it is forced to do when large capital inflows result in a surplus of foreign exchange in the system, since the supply of foreign exchange exceeds demand from firms and individuals for permitted current and capital account transactions such as imports, private or business travel, remittance for gifts, donations, study abroad, medical treatment, investment abroad and so on. When the supply of foreign exchange exceeds such demand, the rupee tends to appreciate vis-ŕ-vis foreign currencies under India's liberalized and market-driven exchange rate regime. A rising rupee increases the dollar value of India's exportables and adversely affects her export competitiveness. It is to prevent such appreciation that the RBI has been purchasing foreign exchange in the market and enhancing its reserves.

Beyond a point, however, increasing reserves are a problem for the central bank. When the foreign exchange assets of the RBI rise, so do its liabilities, which typically imply an increase in money supply. Since allowing that to happen amounts to loosing control of its monetary policy lever, the central bank chooses to retrench other assets such as government securities to sterilize inflows.

Unfortunately for the Reserve Bank of India, foreign capital inflows have in recent months been massive and unrelenting. The consequent huge and rapid increase in its reserves, can no more be sterilized easily, since the central bank has already brought down its holding of government securities substantially.

Excessive reserve accumulation is a problem also because of its negative balance of payments implications. Investors bringing in the capital earn minimum returns of around 7 percent. The maximum would be many multiples of that, especially from capital gains associated with recent investments in the stock market. These returns have to be paid out in foreign exchange. On the other hand, when the dollar flowing into the country are acquired by the RBI and invested through central and commercial banks, the returns are much lower. According to the RBI, during the year 2002-03 (July-June), the return on foreign currency assets, excluding capital gains less depreciation, decreased to 2.8 per cent from 4.1 per cent during 2001-02, because of lower international interest rates. This implies that the interest associated with capital inflow and its accretion as reserves involves little foreign exchange earning but substantial foreign exchange payouts.

Finally, it is becoming diplomatically increasingly difficult to accumulate reserves in order to prevent currency appreciation. India has been identified along with China as a country whose large reserves prove that it has an "undervalued" currency that discriminates against imports from the US. The pressure to allow the currency to appreciate is therefore on the increase.

For all these reasons, it had become clear to the central bank and the government that something had to be done to prevent further rapid reserve accumulation. The choice, therefore, was either to curb flows or to stimulate the demand for foreign exchange. Given its unthinking commitment to liberalization and "reform", it's the latter route that the government has chosen.

Recent months have, therefore, seen not just irrational and sometimes bizarre trade liberalisation manoeuvres, such as across-the-board duty reductions and the license to bring in laptops duty free as part of baggage, but the relaxation of ceilings on remittances abroad for purposes as varied as education, health and investment. All of these have proved inadequate given the fact that India has proved to be the flavour of the season for foreign investors, who have rushed into the country in herd-like fashion.

It is this set of circumstances, rather than rational decision-making, that has forced the government to all on a sudden liberalize controls on capital account outflows. The sequence has to be noted. First, regulations regarding purely financial inflows are liberalized to attract capital into the country so as to finance the outflows that trade liberalization was expected to result in. Since the initial response of foreign investors was lukewarm, further liberalization, in the form of relaxing ceilings on FII holdings of equity in firms in different sectors, was resorted to. Suddenly, for reasons extraneous to the performance of the Indian economy, which has grown at an indifferent rate for at least three consecutive years before the current "recovery", inflows accelerate. Unable to manage those inflows, the government attempts to encourage foreign exchange profligacy through liberalization of foreign exchange access for various current account transactions. When even that proves inadequate, it opts for capital account convertibility.

The problem is that when controls on capital account outflows are liberalized, it is difficult to control the volume of outflows. And if large outflows raise the threat of depreciation in the value of the rupee, outflows accelerate and capital flight out of rupee denominated assets would occur. Having whetted the appetite of India's rich for a financial foothold abroad, it would be extremely difficult to reverse the decision. Moreover, any such reversal would encourage the flight of financial investors out of the country. A currency and financial collapse would be inevitable. In short, the sluice gates have been opened. It is, therefore, clearly time to prepare for the coming crisis.

© MACROSCAN 2004