Taking American Business Back Home

President Barack Obama has unveiled features of a new tax reform

plan as part of his campaign for a second presidency, which, if

implemented, could impact the developing world. Given the rising

debt of the government, the resulting pressure to raise revenues

or cut government expenditures and the evidence that the effective

taxation of America's rich falls short of average, the tax regime

was an issue that any Democratic candidate had to address. The case

for raising tax revenues is strong.

But the opposition to any such increase from many among those who

finance Obama's campaign is also strong. They harp on the fact that

America has the highest marginal corporate tax rate in the world

after Japan. And Japan is reducing its rate from April this year.

So President Obama had to walk the tightrope. That he appears to

have done well by making three distinctions. Between rich individuals

and corporations, between a simple and cumbersome tax system and

between corporations that serve America while serving themselves

and those that only look to their own profits.

By making the first of these distinctions, the President proposes

to tax rich individuals more while reducing taxes on corporates

that create productive assets and provide jobs. He is threatening

to impose the ''Buffett rule'' that those earning more than a million

dollars a year should pay a minimum of 30 per cent of that income

as tax. But to balance this, he has proposed a substantial cut in

the US corporate tax rate from 35 to 28 per cent, with even lower

rates for manufacturing and ''advanced manufacturing''. Clearly,

the idea here is to highlight a push for investment, growth and

jobs.

The second distinction, between a complex and simple tax system,

is made to argue that the reduction in the corporate tax rate needs

to be accompanied by a simplification of the tax system, which eliminates

multiple concessions that introduce distortions. The most obvious

of those distortions is that while the US has among the highest

marginal corporate tax rates in the world, the corporate tax to

GDP ratio in the US is among the lowest among OECD countries. The

US-based Center for Tax Justice has found that the US has the second

lowest corporate tax to GDP ratio in the developed world, falling

only behind Iceland. A study by research firm Capital IQ for the

New York Times found that of the 500 companies included in the Standard

and Poor's stock index, 115 were subject to an effective total (federal

and other) corporate rate of less than 20 per cent during the five

years ending 2010. Yet, over time corporate tax revenues in the

US have fallen from 4 per cent of GDP in 1965 to just 1.3 per cent

in 2009. To justify a corporate tax rate reduction in this context,

President Obama has proposed a rationalisation of the tax system

that puts an end to tax breaks given, for example, to the oil and

gas industry and the private equity business, and benefits such

as accelerated depreciation, which permits companies to write off

assets against tax at a faster rate than they actually depreciate

in economic terms.

Finally, the third distinction, between profits brought back home

and those retained abroad, is made to argue that the President intends

to end the discrimination against firms that provide Americans jobs

by investing profits at home as opposed to retaining them abroad.

It is here that the President was strident: ''Our current corporate

tax system is outdated, unfair, and inefficient. It provides tax

breaks for moving jobs and profits overseas and hits companies that

choose to stay in America with one of the highest tax rates in the

world…It's not right and it needs to change.'' US firms earning

profits abroad and choosing to retain them there are not taxed in

the US on those profits. But if they choose to bring them home then

they are subject to the US corporate tax regime. This does encourage

US corporations to retain and invest their profits abroad, especially

in countries where the effective tax rate is significantly lower

than in the US. Obama now wants to give up this ''territorial''

system of taxing profits of US multinationals and impose a minimum

tax that needs to be paid on overseas profits, whether repatriated

or not.

It is not clear how effective such a system of reducing the differential

tax on repatriated and retained profits would be. But there is evidence

that when tax concessions are offered on profits repatriated back

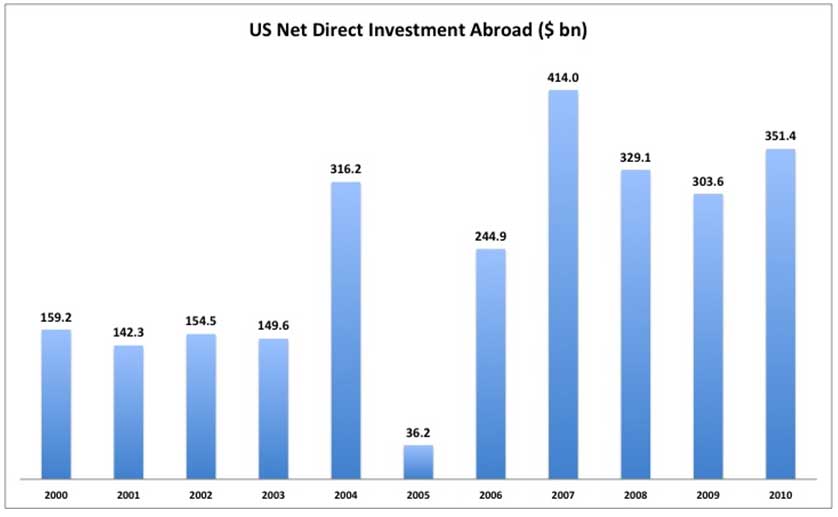

to the US, corporations do respond. As the accompanying Chart shows,

US net direct investment abroad, which ruled high in the latter

part of the last decade, registered a dramatic decline in 2005.

The drop in 2005 reflected the decision by U.S. parent firms to

reduce the amount of reinvested earnings going to their foreign

affiliates, in order to repatriate profits home and take advantage

of one-time tax provisions in the American Jobs Creation Act of

2004 (P.L. 108-357). That act allowed U.S. companies that received

dividends from foreign subsidiaries during a specific period (calendar

year 2004 or calendar year 2005) to be taxed at reduced rates, on

the condition that they worked out a domestic reinvestment plan

for the dividends granted that benefit. Many companies chose to

use that opportunity in 2005, when much of such dividends were paid

out, because the act was signed into law only late in 2004.

If a similar, more long-term, consequence were to follow the implementation

of the proposed reduction in the tax rates on reinvested as opposed

to repatriated overseas profits of US MNCs, US business may at the

margin choose to return home. In this they would also be encouraged

by the fact that in at least one of the countries that is their

favoured destination, viz. China, there are signs of labour shortages

and a rise in wages, besides currency appreciation, which erode

its competitiveness as a location. According to The New York Times,

a report recently released by the Chinese government argues that

this year's post-Spring Festival labour shortage was more pronounced

than in earlier years and also longer and wider in scope. There

are other reports that the migrant worker pool on the basis of which

industry in China's export-oriented zones grew is shrinking. An

important reason is that the government's effort to improve rural

well-being and reduce the rural-urban imbalance is delivering results

and encouraging workers to stay back in their rural homes.

This in itself may not ensure the return home of American business.

Many produce in China because it is the Chinese market that they

are targeting. Others may choose to shift, but to other low-wage

locations rather than back to the US. But the evidence suggests

that Obama's ploy to justify tax concessions to corporations in

a country where they are effectively undertaxed may end up working.

*This article was originally published in

'The Hindu' and is available at

http://www.thehindu.com/opinion/columns/Chandrasekhar/article2953629.ece