Themes > Current Issues

17.05.2004

Jayati

Ghosh

The

mainstream press was almost unanimous in its hysteria. ''Bloodbath'' and

''carnage'' screamed the front page headlines in the English language

press, while editorials sermonised disapprovingly of the apparent irresponsibility

of politicians. Was this all fury about mob frenzy or state-sponsored

riots on the scale of the Gujarat pogrom of two years ago? No, it was

simply that the stock market indices had fallen sharply for the third

day, after it became clear that a Congress-led formation, supported by

the Left parties, would constitute the government at the Centre.

So much of the presentation of economic news, especially in the financial press, is oriented around the behaviour of stock markets, that the uninitiated can be forgiven for thinking that their movements actually reflect real economic performance. Such an interpretation is not exclusive to India. Across the world, ordinary citizens have been conned by the media into believing that the relatively small set of players in international stock markets really do comprehend and correctly assess the patterns of growth in an economy, and that their interests are broadly in conformity with the economic interests of the masses of people in those countries.

This is not simply a deeply undemocratic position (as shown by C.P. Chandrasekhar in his article in the current issue of Frontline). It is also a completely false argument, since it has been abundantly clear for some time now that stock markets are very poor pointers to real economic performance. Stock market indices are indicators of the expectations of finance capital, and they can move up and down for a variety of reasons, most of which are not related even to the current profitability of productive enterprises. They are prone to irrational bubbles and sudden collapses which reflect all sorts of factors, ranging from international forces to domestic political changes, and may have very little relation to economic processes within the economy.

Consider the latest fall in the Indian stock market. While it is true that some of it is clearly a reaction to the uncertainty created by the unexpected and remarkable defeat of the NDA government at the polls, it also should be noted that across the world, financial markets have been in downswing in recent weeks. The New York Stock Exchange composite index fell by 4 per cent between 5 May and 14 May, and other markets across Europe and Asia have shown similar or even larger falls. Much of this is because of rising oil prices, the failure of the economically and politically expensive US military occupation in Iraq, and fears of interest rate hikes in the US.

It is true that the Bombay Sensex index fell by more than 10 per cent and the Nifty index by 12 per cent over the same period, but this is still part of a more general worldwide trend of decrease in stock values, and some market analysts have even described these as necessary ''corrections'' of the earlier inflated values.

For the past year, Indian stock prices had been pushed up by large inflows from foreign portfolio investors, who had recently ''discovered'' India as an attractive emerging market that has not yet had a financial crisis. This meant that, despite the fact that very little had changed in the so-called ''fundamentals'' of the economy, there were substantial inflows from financial investors that also caused the rupee to appreciate.

Foreign investors use emerging markets like India to hedge against changes in other markets; they also like to focus on particular countries in any one period, where herd behaviour creates a boom and the countries concerned become the temporary darlings of international capital. In India in the recent past, the numerous concessions provided by the NDA government to such mobile capital also allowed for large super-profits to be made through such transactions.

Because the Indian stock market still has relatively thin trading, these foreign institutional investors made a big difference at the margin, and were responsible for pushing up stock values well beyond what would be ''sensible'' values according to standard international norms of price-equity ratios. This is typical of the bubbles that have been created by internationally mobile finance in various developing countries, especially since the early 1990s.

It is inevitable that such bubbles must eventually come to an end, whether through a sharp burst in the shape of a financial crisis or through a slower and more managed shrinking of values. When this happens, it is true that a lot of players who have put their bets on continuously rising share values will be affected, but this need not mean that there has been any other bad news in the economy.

Of course, it is always difficult to attribute causes to stock market movements, since financial markets are notoriously prone to ''noise'' and irrational behaviour. However, more than the actual causes, the implications of such falls are what matter to most of us, and this is where the mainstream media have been the most misleading.

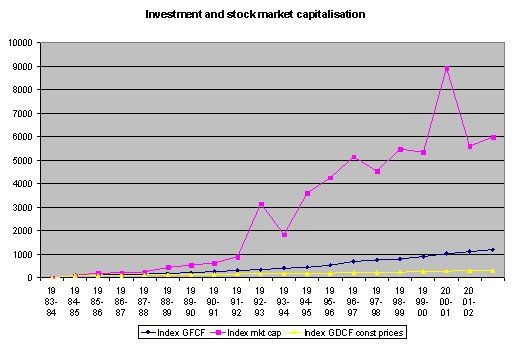

It is usually argued that stock market behaviour is a reflection of ''investor confidence'' and this in turn affects important real variables such as productive investment in the economy, which is critical for growth and development. This is not really the case, and has become even less true in the recent period. Especially since the early 1990s, the stock market has experienced huge increases and wild swings, while investment has not shown any such volatility and indeed has barely increased in real terms.

This is evident from the chart below, which shows the index of stock market capitalisation in India since the early 1980s. Stock market capitalisation increased by around 4 times in the decade 1991-92 to 2001-02, with very large fluctuations in between. By contrast, total gross fixed capital formation in the economy increased much less even in current prices, and in constant prices it barely doubled.

So much of the presentation of economic news, especially in the financial press, is oriented around the behaviour of stock markets, that the uninitiated can be forgiven for thinking that their movements actually reflect real economic performance. Such an interpretation is not exclusive to India. Across the world, ordinary citizens have been conned by the media into believing that the relatively small set of players in international stock markets really do comprehend and correctly assess the patterns of growth in an economy, and that their interests are broadly in conformity with the economic interests of the masses of people in those countries.

This is not simply a deeply undemocratic position (as shown by C.P. Chandrasekhar in his article in the current issue of Frontline). It is also a completely false argument, since it has been abundantly clear for some time now that stock markets are very poor pointers to real economic performance. Stock market indices are indicators of the expectations of finance capital, and they can move up and down for a variety of reasons, most of which are not related even to the current profitability of productive enterprises. They are prone to irrational bubbles and sudden collapses which reflect all sorts of factors, ranging from international forces to domestic political changes, and may have very little relation to economic processes within the economy.

Consider the latest fall in the Indian stock market. While it is true that some of it is clearly a reaction to the uncertainty created by the unexpected and remarkable defeat of the NDA government at the polls, it also should be noted that across the world, financial markets have been in downswing in recent weeks. The New York Stock Exchange composite index fell by 4 per cent between 5 May and 14 May, and other markets across Europe and Asia have shown similar or even larger falls. Much of this is because of rising oil prices, the failure of the economically and politically expensive US military occupation in Iraq, and fears of interest rate hikes in the US.

It is true that the Bombay Sensex index fell by more than 10 per cent and the Nifty index by 12 per cent over the same period, but this is still part of a more general worldwide trend of decrease in stock values, and some market analysts have even described these as necessary ''corrections'' of the earlier inflated values.

For the past year, Indian stock prices had been pushed up by large inflows from foreign portfolio investors, who had recently ''discovered'' India as an attractive emerging market that has not yet had a financial crisis. This meant that, despite the fact that very little had changed in the so-called ''fundamentals'' of the economy, there were substantial inflows from financial investors that also caused the rupee to appreciate.

Foreign investors use emerging markets like India to hedge against changes in other markets; they also like to focus on particular countries in any one period, where herd behaviour creates a boom and the countries concerned become the temporary darlings of international capital. In India in the recent past, the numerous concessions provided by the NDA government to such mobile capital also allowed for large super-profits to be made through such transactions.

Because the Indian stock market still has relatively thin trading, these foreign institutional investors made a big difference at the margin, and were responsible for pushing up stock values well beyond what would be ''sensible'' values according to standard international norms of price-equity ratios. This is typical of the bubbles that have been created by internationally mobile finance in various developing countries, especially since the early 1990s.

It is inevitable that such bubbles must eventually come to an end, whether through a sharp burst in the shape of a financial crisis or through a slower and more managed shrinking of values. When this happens, it is true that a lot of players who have put their bets on continuously rising share values will be affected, but this need not mean that there has been any other bad news in the economy.

Of course, it is always difficult to attribute causes to stock market movements, since financial markets are notoriously prone to ''noise'' and irrational behaviour. However, more than the actual causes, the implications of such falls are what matter to most of us, and this is where the mainstream media have been the most misleading.

It is usually argued that stock market behaviour is a reflection of ''investor confidence'' and this in turn affects important real variables such as productive investment in the economy, which is critical for growth and development. This is not really the case, and has become even less true in the recent period. Especially since the early 1990s, the stock market has experienced huge increases and wild swings, while investment has not shown any such volatility and indeed has barely increased in real terms.

This is evident from the chart below, which shows the index of stock market capitalisation in India since the early 1980s. Stock market capitalisation increased by around 4 times in the decade 1991-92 to 2001-02, with very large fluctuations in between. By contrast, total gross fixed capital formation in the economy increased much less even in current prices, and in constant prices it barely doubled.

More to the point, the large swings in market capitalisation were not

associated with any commensurate changes in investment, suggesting that

the financial markets dance to a bizarre tune that is all their own, and

do not have much impact on real investment in the economy. This is very

important to underline, because the reason that we are all supposed to

be concerned about stock market behaviour is because of its supposed effect

on investment. In fact, it is really only those agents who are dependent

upon the return from finance capital who are affected, while real investment

depends upon many other factors.

The other impact that movements in the stock market have nowadays is on the exchange rate, especially since so much of the change is caused by the behaviour of foreign institutional investors. Their movements over the past year have helped to build up the RBIís foreign exchange reserves to an almost embarrassing amount, partly because their inflows are not being used to increase productive investment, and partly because the RBI kept buying dollars in an effort to keep the rupee from appreciating even further.

While the large forex reserves may have provided a macho feeling of false confidence to some, in reality they were a reflection of huge macroeconomic waste, since they implied that the capital inflows were not being productively used. They were also expensive for the economy to hold, since the interest received on such reserves by the RBI is typically very low, whereas the external commercial borrowing by Indian firms in the current liberalised environment was at significantly higher interest rates.

In this background, some dilution of the forex reserves may even be welcome. Of course, if the current outflow turns into a capital flight which is also joined by Indian residents, then clearly the situation can become more serious. Such a possibility is now more open because of all the recent measures liberalising capital outflow that the NDA government brought in during the closing months of its rule. The new government may have to address some of these measures quite quickly, to prevent excessive capital outflows which can then become another means of pressurising the government on its economic policies.

But otherwise, the current downslide in the stock markets is really not a matter of serious concern for most Indians, and it should certainly not be much of an issue for the new government either. The mainstream English language media, whose business interests increasingly coincide with those of finance capital, may continue to shout itself hoarse about it. But then, as the recent electoral cataclysm has shown, these media also do not reflect the interests of the Indian people, nor do they even understand them.

The other impact that movements in the stock market have nowadays is on the exchange rate, especially since so much of the change is caused by the behaviour of foreign institutional investors. Their movements over the past year have helped to build up the RBIís foreign exchange reserves to an almost embarrassing amount, partly because their inflows are not being used to increase productive investment, and partly because the RBI kept buying dollars in an effort to keep the rupee from appreciating even further.

While the large forex reserves may have provided a macho feeling of false confidence to some, in reality they were a reflection of huge macroeconomic waste, since they implied that the capital inflows were not being productively used. They were also expensive for the economy to hold, since the interest received on such reserves by the RBI is typically very low, whereas the external commercial borrowing by Indian firms in the current liberalised environment was at significantly higher interest rates.

In this background, some dilution of the forex reserves may even be welcome. Of course, if the current outflow turns into a capital flight which is also joined by Indian residents, then clearly the situation can become more serious. Such a possibility is now more open because of all the recent measures liberalising capital outflow that the NDA government brought in during the closing months of its rule. The new government may have to address some of these measures quite quickly, to prevent excessive capital outflows which can then become another means of pressurising the government on its economic policies.

But otherwise, the current downslide in the stock markets is really not a matter of serious concern for most Indians, and it should certainly not be much of an issue for the new government either. The mainstream English language media, whose business interests increasingly coincide with those of finance capital, may continue to shout itself hoarse about it. But then, as the recent electoral cataclysm has shown, these media also do not reflect the interests of the Indian people, nor do they even understand them.

© MACROSCAN

2004