Themes > Current Issues

17.11.2011

European Banks and Asia

C.P. Chandrasekhar

and Jayati Ghosh

Initially,

the still-evolving crisis in Europe was read as being the result of

excess public debt and poor public finances. Though this debt was

owed to the banks, especially European banks, the latter were seen

as protected. Default on debt owed to them would damage the financial

system, worsen the real economy crisis, break the Eurozone and end

the euro. Governments that had come together to constitute the Eurozone

and adopt a common euro would hardly opt for this scenario stemming

from a default by them that could damage bank profitability. Using

that argument, the financial community worked overtime to call for

action that would save the banks at the expense of the countries of

the Eurozone and their populations.

It is now clear, however, that this strategy would not work. Governments seeking to ''adjust'' through austerity are finding their public finances worsening rather than improving, eroding further their ability to avoid a default on debt commitments. Thus, banks are being required to take a haircut, currently set at 50 per cent of loan value, up from 20 per cent a few months earlier. This could get even higher.

Given the damage that this would do to bank profits and balance sheets, a recapitalisation of European banks is imperative, with the current overly conservative estimate placing the funds required for that purpose at €106 billion. In addition, with European regulators set to agree on a revised core (tier one) capital ratio of 9 per cent for their banks, this figure could go up to €275 billion, according to Morgan Stanley. As of now, banks are required to dig into their global reserves (if any), approach the private markets for debt and equity, as well as take support from governments, through the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF). But with most European governments unwilling or unable to provide funds, the EFSF's future strength is still uncertain. Thus, a significant retrenchment of still performing assets by European banks and a persisting and possibly worsening real economy crises seems unavoidable as of now.

This has led to much discussion on how a European banking crisis would affect the rest of the world. Our concern here is with the impact on developing countries, especially the developing countries or the ''emerging markets'' in Asia exposed significantly to global banks.

It is now well accepted that one of the consequence of financial globalization has been the increased presence of global banks in developing countries and an increase in their role as lenders in these countries. This process has, of course unfolded to different degrees in different regions of the world. Between 1995 and 2005, the share of foreign banks in total bank assets rose from 25 to 58 per cent in Eastern Europe and from 18 to 38 per cent in Latin America, though even by that date the increase in East Asia and Oceania was much less (from 5 to 6 per cent). With this increase in presence, the share of foreign banks in lending to non-bank residents has been rising. Since the mid-1990s (and by 2009) the share of foreign banks in credit to non-bank residents rose from 30 to 50 per cent in Latin America, to nearly 90 per cent in emerging Europe, but is still at about 20 per cent in emerging Asia.

It is now clear, however, that this strategy would not work. Governments seeking to ''adjust'' through austerity are finding their public finances worsening rather than improving, eroding further their ability to avoid a default on debt commitments. Thus, banks are being required to take a haircut, currently set at 50 per cent of loan value, up from 20 per cent a few months earlier. This could get even higher.

Given the damage that this would do to bank profits and balance sheets, a recapitalisation of European banks is imperative, with the current overly conservative estimate placing the funds required for that purpose at €106 billion. In addition, with European regulators set to agree on a revised core (tier one) capital ratio of 9 per cent for their banks, this figure could go up to €275 billion, according to Morgan Stanley. As of now, banks are required to dig into their global reserves (if any), approach the private markets for debt and equity, as well as take support from governments, through the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF). But with most European governments unwilling or unable to provide funds, the EFSF's future strength is still uncertain. Thus, a significant retrenchment of still performing assets by European banks and a persisting and possibly worsening real economy crises seems unavoidable as of now.

This has led to much discussion on how a European banking crisis would affect the rest of the world. Our concern here is with the impact on developing countries, especially the developing countries or the ''emerging markets'' in Asia exposed significantly to global banks.

It is now well accepted that one of the consequence of financial globalization has been the increased presence of global banks in developing countries and an increase in their role as lenders in these countries. This process has, of course unfolded to different degrees in different regions of the world. Between 1995 and 2005, the share of foreign banks in total bank assets rose from 25 to 58 per cent in Eastern Europe and from 18 to 38 per cent in Latin America, though even by that date the increase in East Asia and Oceania was much less (from 5 to 6 per cent). With this increase in presence, the share of foreign banks in lending to non-bank residents has been rising. Since the mid-1990s (and by 2009) the share of foreign banks in credit to non-bank residents rose from 30 to 50 per cent in Latin America, to nearly 90 per cent in emerging Europe, but is still at about 20 per cent in emerging Asia.

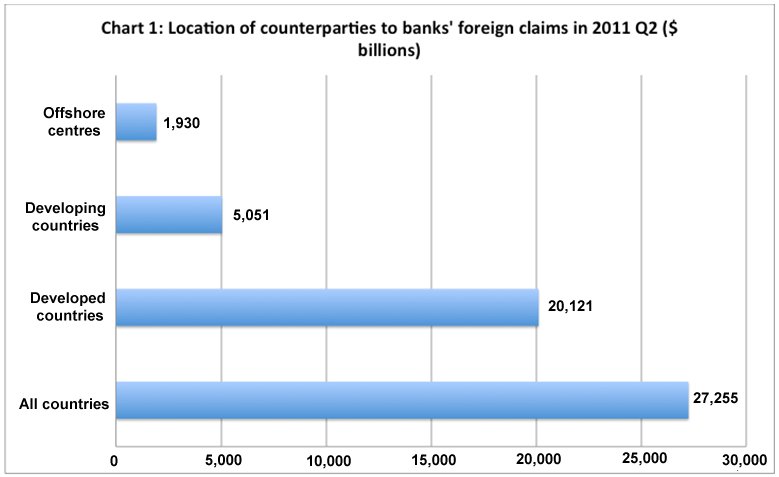

As of the end of the second quarter of 2011, banks in countries

reporting to the Bank of International Settlements (BIS) had foreign

claims of $27.3 trillion outstanding. Though a dominant share ($20.1

trillion) of these accumulated claims was in the developed countries,

the developing country share ($5.1 trillion) was by no means meagre

(Chart 1). What is particularly noteworthy is that the international

banks involved are predominantly European. Around 70 per cent of

the foreign claims of the global banking system is on account of

European banks. Greater financial integration in Europe is one obvious

reason. Of the $20.1 trillion claims on the developed countries,

$12.3 trillion is in European developed countries, as compared with

just $5.6 trillion in the US.

But another part of the reason is that European banks faced with

increased competition at home are now seeking out developing countries

to expand business and sustain profitability. Close to 20 per cent

of the exposure of banks abroad is in developing countries, and

this is true of European banks as well (Table 1). Given the greater

role of European banks in total international funding and the importance

of a few developing ''emerging markets'' as recipients of capital,

this is of significance. The concentration of emerging market exposure

in banks from one region increases the vulnerability of both these

banks and their clients. But as discussed below, given the asymmetric

nature of the relationship between foreign banks and their emerging

market clients, this vulnerability is the greater for the latter,

especially in the context of the current crisis in Europe.

Table

1: Foreign exposure of banks by region (Per cent) |

||

|

00

|

All

banks |

European

banks |

| Developed | 73.8 |

74.7

|

| European Developed | 45.3 |

49.3

|

| US | 20.7 |

20.0

|

| Offshore Centres | 7.1 |

5.8

|

| Developing | 18.5 |

18.9

|

| Dev'ing Af & ME | 2.2 |

2.6

|

| Dev'ing Asia & Pacific | 6.5 |

4.9

|

| Dev'ing Europe | 5.2 |

6.9

|

| Dev'ing LA&C | 4.6 |

4.5

|

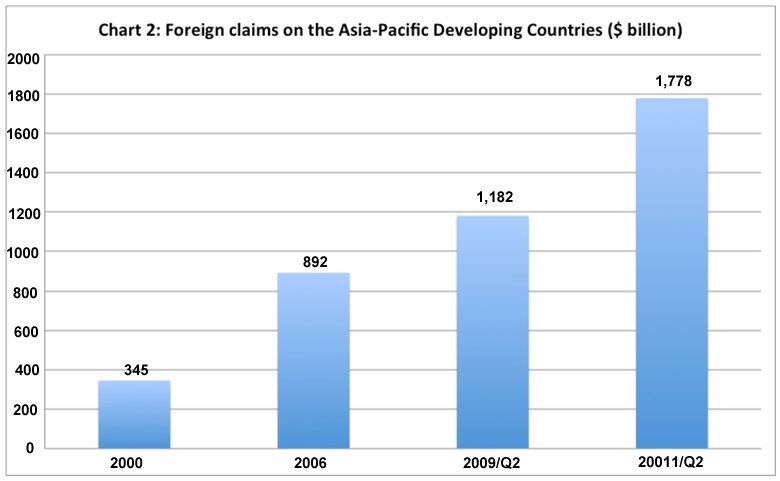

In the current context, the vulnerability of the developing countries, as demonstrated by the experience during the 2008-09 crisis, comes especially from one source. Having to cover losses at home, recapitalise themselves and improve the risk profile of their lending, European banks are likely to look to transferring profits and retrenching assets in their global operations. Emerging markets are bound to be affected by such moves. Among emerging markets, those in the Asia-Pacific, normally presented as relatively ''decoupled'' from the developed West, are just as vulnerable. As much as $1.8 trillion of the $5.1 trillion of global banking foreign claims located in developing countries are in the Asia-Pacific.

The disconcerting feature of these claims is that they seem to have been driven to a substantial degree by short-term supply side developments in the developed countries. As Chart 2 shows, foreign claims on the Asia-Pacific developing countries rose by $547 billion during the period 2000-2006, when there occurred a supply side driven surge in capital flows across the globe. Even during the crisis period stretching from 2007 to the middle of 2009 foreign bank claims in the region increased by $290 billion. And when the post-crisis liquidity infusion made available cheap capital in large quantities to the banking system, the Asia-Pacific developing countries were the locations for an expansion of foreign bank claims to the tune of $596 billion in just two years. A capital surge of this kind, that provided additional grounds for the ''decoupling'' perspective, makes the region even more vulnerable to a capital outflow or a mere cutback in lending by foreign entities.

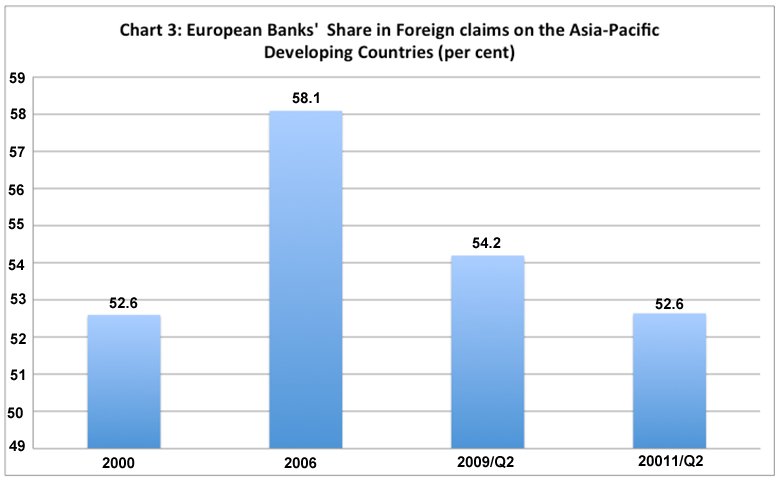

Given what we noted earlier, this vulnerability is greater because of the importance of European banks in the region. The share of European banks in these claims in the developing Asia-Pacific rose from 53 to 58 per cent between 2000 and 2006, and has since fallen to 52.6 per cent (Chart 3). Part of the reason for that decline is the fact that the liquidity infusion into the banking system has been far more in the US than in Europe in the aftermath of the crisis. But it is also a reflection of the fact that European banks have been turning more cautious and possibly retrenching assets when they mature, to transfer funds to their parent entities.

Table

2: Accumulated Foreign Bank Claims as a Percentage of GDP in Emerging Asia |

||||||

| 00 |

China |

Indonesia |

India

|

Korea |

Malaysia |

Thailand |

2005 |

3.3 |

9.0 |

9.7 |

24.2 |

52.7 |

18.6 |

2006 |

4.7 |

9.3 |

12.3 |

27.1 |

54.1 |

20.1 |

2007 |

6.1 |

10.8 |

16.0 |

31.6 |

55.9 |

18.2 |

2008 |

3.9 |

9.4 |

15.1 |

29.3 |

44.5 |

17.1 |

2009 |

4.6 |

10.0 |

14.9 |

37.5 |

53.6 |

21.7 |

2010 |

6.1 |

10.5 |

15.3 |

31.4 |

52.6 |

22.9 |

That being said, how important are these foreign bank claims to

the Asia-Pacific developing countries? It is indeed true that in

many of them the annual flows of capital that those claims represent

are small when compared to the aggregate annual flow of debt, equity

and other claims. However, as accumulated claims these do constitute

a significant amount relative to GDP in most Asian emerging markets,

excluding China (Table 3). At 15-20 per cent in India and Thailand

and as much as 30-50 per cent in Korea and Malaysia, these accumulated

claims are a source for concern. Any sudden retrenchment can create

liquidity as well as foreign exchange difficulties.

This vulnerability needs to be assessed in the context of the collateral

damage that a banking crisis in Europe can result in. It would worsen

the recession in Europe, which is an important destination for exports

from Asia. The recession in Europe would in turn precipitate the

double dip that can damage Asia's foreign exchange earnings and

growth even more. And finally, the European banking crisis could

trigger a global crisis, not just in banking but in the financial

sector generally, given the multiple institutions and instruments

through which financial markets are interlinked today. If that occurs,

what matters is the aggregate exposure of the Asia-Pacific to global

capital: and that is indeed substantial. Asia too needs to look

to protecting itself in the near future.

© MACROSCAN 2011