Themes > Current Issues

11.10.2010

Market Madness Again

C.P. Chandrasekhar

Over

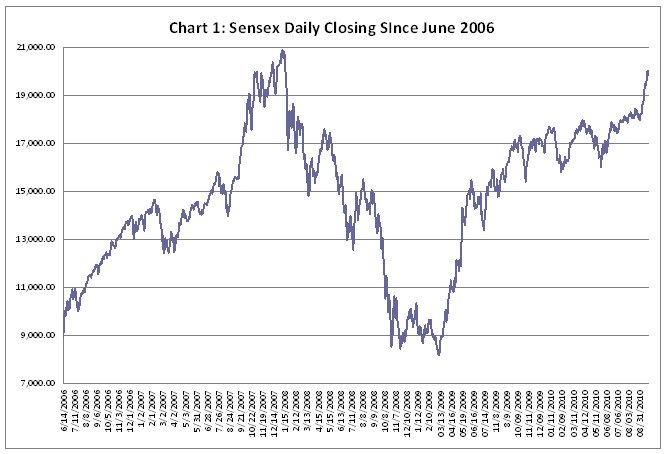

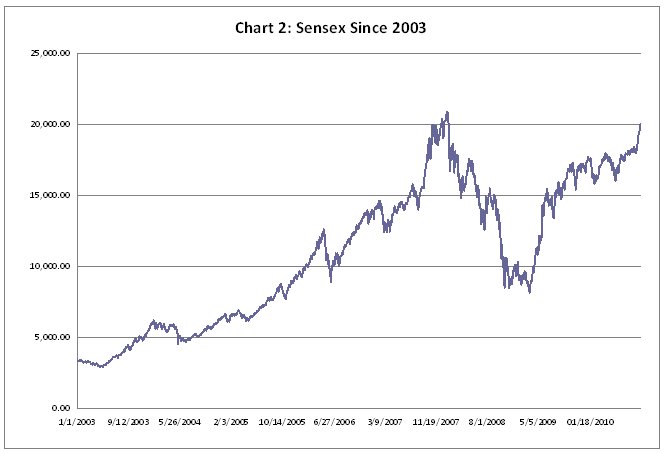

the week ending September 24, there were two days in which the Sensex

closed at over 20,000. Having soared from its March 9, 2009 low of

8,160, the Sensex touched 20,045 at closing on September 17, 2010.

This is not far short of the 20,873 peak the index closed at on January

8, 2008, after which it collapsed. It also amounts to a rise of around

150 per cent in a little more than 18 months. This steep increase

occurred when the after effects of the global crisis were still being

felt in various parts of the world where the recovery has been halting

and unemployment still rampant.

There is little disagreement on the fact that this spike in stock

prices is the result of a sudden surge of foreign capital inflow into

the stock market. Foreign Institutional Investors (FIIs) who opted

for net equity sales of $14.84 billion during crisis year 2008, quickly

returned to the Indian market and made net purchases worth $17.23

billion during 2009. During 2010 that positive figure had touched

$15.62 billion even by the middle of September.

The actual impact of FII investment on equity prices is much more

than these numbers suggest. Figures from the Reserve Bank of India

indicate that not only did foreign portfolio investment, which fell

from $27.3 billion in 2007-08 to a negative $13.86 billion in 2008-09,

bounce back to $32.38 billion in 2009-10, but foreign direct investment

has risen consistently from $34.83 billion to $35.18 billion and $37.18

billion over these years. In the event total foreign investment was

close to a record $70 billion in 2009-10. Since any investment equal

to or exceeding 10 per cent of stock in a company by a single foreign

investor is defined as direct investment, a significant amount of

investment seeking capital gains gets treated as direct investment

with a productive interest in the figures. Thus, speculative financial

investments are likely to have been significantly higher in recent

months.

The impact of such flows on a market that is neither deep nor wide

is well known. There are few firms whose shares are actively traded

in the market and a small proportion of the shares of even these companies

are free-float shares not held by the promoters and potentially available

for trading. When there is a capital inflow surge, a lot of money

pursues a relatively small no of shares. So, more than in other contexts,

any sudden inflow of capital would result in sharp stock price increases.

In the circumstances, there are two ways to approach the recent stock

price boom. One is to recognise that the market has become extremely

volatile and that it is plagued by speculation and asset price inflation.

The rapid rise in stock prices cannot be justified by movements in

corporate sales and profits, and price earnings ratios of many Sensex

companies stand at levels which many market observers see as unsustainable.

In fact, otherwise bullish investment advisors are recommending that

investors should book profits and hold cash till the market corrects

itself. This implies that the current bull run can be explained only

as being the result of a speculative surge that recreates the very

conditions that led to the collapse of the Sensex from its close to

21,000 peak of around two years ago.

The other approach to these stock price movements is to treat the

spike in prices as a sign of investor confidence and therefore of

the health of the economy. Thus Finance Minister Pranab Mukherjee

had declared that while ''the Sensex is always a little bit unpredictable'',

he was ''happy that for the first time after January 2008'' it had

crossed 20,000. Finance Secretary Ashok Chawla has gone even further.

He is quoted as saying that the stock market boom reflects the confidence

of investors in the India growth story, that it was a vote of confidence

by foreign institutional investors (FIIs), and that he does not see

the surge in foreign capital flows into India's share market posing

any problem as of now.

It is not surprising that foreign institutional investors have returned

to the market. Since the crisis hit the world economy, they have been

seeking ways of recouping losses suffered at home during the financial

meltdown. And they have been helped in that effort by the large volumes

of credit provided at extremely low interest rates by governments

and central banks in the developed countries seeking to bail out fragile

and failing financial firms. The credit crunch at the beginning of

the crisis gave way to an environment awash with liquidity as governments

and central bankers pumped money into the system at near-zero interest

rates. Financial firms have chosen to borrow and invest this money

in markets where returns are promising so as to quickly turn losses

into profit. Some was reinvested in government bonds in the developed

countries, since governments were lending at rates lower than those

at which they were borrowing. Some was invested in commodities markets,

leading to a revival in some of those markets. And some returned to

the stock and bond markets, including those in the so-called emerging

markets like India. Many of these bets, such as investments in government

bonds, were completely safe. Others such as investments in commodities

and equity were risky. But the very fact that money was rushing into

these markets meant that prices would rise once again and ensure profits.

In the event, bets made by financial firms have come good, and most

of them have begun declaring respectable profits and recording healthy

stock market valuations.

It is to be expected that a country like India would receive a part

of these new investments aimed at delivering profits to private players

but financed at one remove by central banks and governments. The ''carry

trade'' – where money is borrowed at low interest rates in one currency

and invested in a foreign market with high returns – would yield good

profits, especially since the inflow of capital would itself drive

price increases and push the value of the currency to higher levels.

India has received more than a fair share of these investments. One

reason for this is the fact that India fared better during the recession

period than many other developing counties and was therefore a preferred

hedge for investors seeking investment destinations. The other reason

is the expectation fuelled by statements by spokespersons of the UPA

government that it intends to push ahead with the ever-unfinished

agenda of economic liberalisation and ''reform''. The UPA II government

has announced and begun implementing its decision to disinvest equity

and/or privatise major public sector units. It is further relaxing

caps on foreign direct investment in a wide range of industries. And

corporate tax rates are likely to be reduced and capital gains taxes

perhaps abolished. In sum, whether intended or not, the signals emanating

from the highest economic policy making quarters have helped talk

up the Indian market, allowing equity prices to race ahead of earnings

and fundamentals. The net result is the current speculative boom that

seems as much a bubble as the one that burst not so long ago. What

is more, that bubble is being expanded by the strengthening of the

rupee that the capital inflows result in, which promises even higher

returns on carry trade investments.

The spike in stock prices and the strengthening of the rupee are signals that it is time the government acted to regulate and limit the capital inflows that are generating these speculative trends. But while the government and the central bank are responding to inflation in the prices of goods they are choosing to ignore the much sharper inflation in asset prices. This amounts to ignoring the fact that India today is the ''victim'' of the decision of the developed countries to use liquidity injection and credit expansion as the principal instrument to combat the Great Recession. This has resulted in a capital inflow surge that generates a speculative bubble as well as leads to rupee appreciation that affects the competitiveness of our exports. Yet, goaded by financial interests and an interested media, the government treats the boom as a sign of economic good health rather than a sign of morbidity. The crisis, clearly, has not taught most policy makers any lessons.

© MACROSCAN 2010