Themes > Features

25.04.2005

The Chinese Bogeyman in US Clothing

On April 4, the US Department of Commerce succumbed to protectionist pressures and chose to launch investigations to check whether textile imports from China were disrupting US markets. US Commerce Secretary, Carlos Gutierrez, is reported to have said that the decision was the first step in a process to determine whether the US market for these products is being disrupted and whether China is playing a role in that disruption. The immediate excuse was evidence of a sharp rise in the quantum of imports of certain varieties of Chinese textiles into the US market, quota restrictions on which under the Multi-Fibre Agreement (MFA) were lifted as of January 1, 2005. As Table 1 indicates, import increases during the first quarter of the year in select categories that are controversial have varied from an excess of 250 per cent to as much as 1600 per cent. However, there is need for caution when quoting these figures, because they are growth rates computed on a base kept low by the MFA's quota regime.

Table

1: Increase in Imports of Specific Categories of Textiles: Jan-March

2005 |

||||

Category |

Volume

Growth (Percentage)

|

|||

Cotton

Hosiery |

1084

|

|||

Cotton

Knit Shirts, MB |

1003

|

|||

W/G

Knit Blouse |

1499

|

|||

Cotton

Skirts |

1102

|

|||

Cot.M/B

Trousers |

1492

|

|||

W/G

Slacks, etc. |

1612

|

|||

Cotton

Underwear |

408

|

|||

M-MF

Underwear |

260

|

|||

But

touting such figures, US industry associations have been accusing the

Chinese of dumping to an extent that disrupts the US market and damages

the domestic industry. In the event, they are demanding that the government

should invoke a clause included in China's WTO accession conditions

that permits the US government to restrict import growth to 7.5 per

cent a year till 2008. The Bush government that has recently begun its

second term has been quick to oblige, even though domestic political

pressures are not as overwhelming.

There are, however, a number of reasons to hold that the US response

is either alarmist or orchestrated to justify a protectionist response.

We must recognise that quotas under the MFA, which limited the quantum

of exports into individual segments of the global textile market from

the most competitive textile exporters, had two kinds of effects. First,

it reduced the competition faced by US (domestic) suppliers of textiles

from imports from the most cost-competitive centres of global textile

production, allowing the former to sustain higher levels of output.

Second, it reduced competition between exporters from more and less

competitive locations targeting the same market, by restricting the

volume of exports from more competitive producers.

As a result of these two different forces at play, the lifting of quotas

was expected to have two different effects. One was an increase in the

total quantum of imports of restricted items into individual markets

because of increased imports from all locations that are cost-competitive

relative to domestic suppliers. The second was a re-division of an individual

market among exporters, with more cost-competitive suppliers displacing

less cost-competitive ones in individual segments.

As

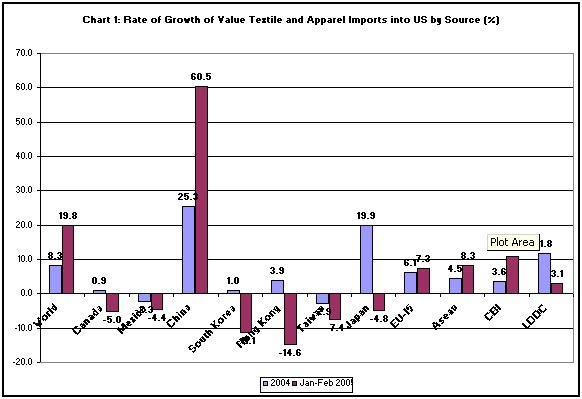

Chart 1 makes clear, both these tendencies are visible in the US market.

Considering all items of textile and apparel imports, the US trade balance

report which provides the most comprehensive data, indicates that total

imports into the US market rose by close to 20 per cent in the first

two months of 2005 (relative to the corresponding period of the previous

year) as compared with 8.3 per cent during 2004. Thus the removal of

quotas did result in a substantial increase in imports into the US market

that would have resulted in some displacement of domestic production.

However, the increase in imports from China, which amounted to 60.5

per cent during January-February 2005 as compared with 25.3 per cent

in 2004, was not wholly directed at the displacement of US production.

Rather, increased imports from China were accompanied by a decline or

slowing down of imports from other sources such as Mexico, South Korea,

Hong Kong, Taiwan and Japan. That is, after the removal of quotas, Chinese

imports were outcompeting imports into the US from other sources that

were earlier “protected” by the MFA regime.

This is not to say, however, that China is wiping the floor clean. There

are other countries such as the EU-15, the ASEAN countries and countries

belonging to the Caribbean Basin Initiative (CBI) that have been able

to increase the rate of expansion of their exports. What is disconcerting

however is that the Least Developed Countries (LDCs), which do not receive

the same special benefits as the CBI group in US markets, have seen

a significant decline in the rate of growth of their exports to the

US market. But this may partly be due to the disruption caused by the

tsunami in at least some of these countries, such as Mauritius.

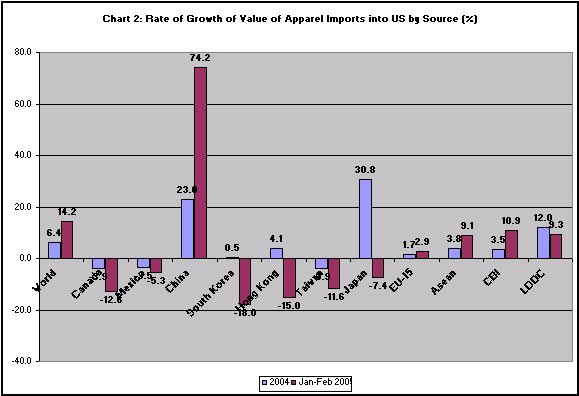

Some of these features are sharper if we consider an area like apparel,

which is where the bulk of the increase in imports into the US from

China has taken place. As Chart 2 indicates, while China's apparel exports

to the US grew by close to 75 per cent during the first two months of

2005, as compared with 23 per cent during 2004, this was accompanied

by a substantial degree of displacement of imports from Canada, Mexico,

South Korea, Hong Kong and Taiwan. Further, besides increases in imports

from country-groupings such as the EU-15, ASEAN and the CBI, LDCs have

registered a much smaller decline in the rate of growth of imports than

is suggested by aggregate figures.

In sum, not all of China's dramatic export increase during the first

quarter of 2005 was on account of the displacement of US production.

It was partly because of displacement of export increases from other

countries. And there were countries other than China which contributed

to the growth in overall textile imports into the US. Above all, as

Table 2 makes clear, the effect of the increase in Chinese exports on

exports to the US from individual developing countries has not been

as adverse as had been expected.

Table

2: US Textile Imports by Country Major Shipper's Report ($ Mill.) |

||||||

Growth

Rate |

||||||

2003 |

2004 |

Jan-Feb 2004 |

Jan-Feb 2005 |

Jan-Feb 2004 |

Jan-Feb 2005 |

|

World |

77434 |

83312 |

12284.1 |

14010

|

7.6 |

14.0 |

China |

11608.8 |

14559.9 |

2002.9 |

3362.4

|

25.4 |

67.9 |

Asean |

11678.2 |

12143.6 |

1867.7 |

2014

|

4.0 |

7.8 |

CAFTA |

9244.6 |

9578.6 |

1266.9 |

1408.4

|

3.6 |

11.2 |

EU-15 |

4336.5 |

4530 |

687.5 |

730.9

|

4.5 |

6.3 |

Sub-Sahara |

1534.9 |

1781.8 |

253.2 |

282.5

|

16.1 |

11.6 |

Bangladesh |

1939.4 |

2065.7 |

324.6 |

359.4

|

6.5 |

10.7 |

Cambodia |

1251.2 |

1441.7 |

234.3 |

259.1

|

15.2 |

10.6 |

Fiji |

79.6 |

85.8 |

13.9 |

7.7

|

7.8 |

-44.6 |

India |

3211.5 |

3633.4 |

588.1 |

737

|

13.1 |

25.3 |

Indonesia |

2375.7 |

2620.2 |

445.4 |

477.6

|

10.3 |

7.2 |

Japan |

522.4 |

641.7 |

78.3 |

79.8

|

22.8 |

1.9 |

South

Korea |

2567 |

2579.7 |

393.9 |

344.3

|

0.5 |

-12.6 |

Laos |

3.9 |

2.1 |

0.3 |

0.1

|

-46.2 |

-66.7 |

Malaysia |

737.5 |

764.3 |

117.3 |

109.8

|

3.6 |

-6.4 |

Maldives |

93.7 |

81 |

12.5 |

4.7

|

-13.6 |

-62.4 |

Mauritius |

269.1 |

226.6 |

43.1 |

37.5

|

-15.8 |

-13.0 |

Mexico |

7940.8 |

7793.3 |

1144.9 |

1097.2

|

-1.9 |

-4.2 |

Mongolia |

181.1 |

229.1 |

25.8 |

21.7

|

26.5 |

-15.9 |

Nepal |

155.3 |

130.6 |

25.9 |

16

|

-15.9 |

-38.2 |

Pakistan |

2215.2 |

2546 |

371.4 |

396.9

|

14.9 |

6.9 |

Philippines |

2040.3 |

1938.1 |

323.6 |

299.9

|

-5.0 |

-7.3 |

Singapore |

270.8 |

244.1 |

34.1 |

34.1

|

-9.9 |

0.0 |

Sri

Lanka |

1493 |

1585.2 |

258.6 |

305.5

|

6.2 |

18.1 |

Taiwan |

2185 |

2103.9 |

308.3 |

283.6

|

-3.7 |

-8.0 |

Thailand |

2071.7 |

2198.2 |

314.1 |

372.8

|

6.1 |

18.7 |

Vietnam |

2484.3 |

2719.7 |

361.8 |

430.2

|

9.5 |

18.9 |

What

needs to be noted is that the displacement of US production, to the

extent that it occurred, is a sign that the US has not adequately restructured

its industry during the long years of protection resorted to for this

very purpose. The protection afforded to developed country textile production

with the aim of restructuring those industries began in the 1961, when

the Long Term Agreement on textiles was signed. That agreement provided

the developed countries with a 10-year respite, during which they were

expected to either phase out a part of their uncompetitive textile production,

“burdened” by high wages, or modernise their textile industries to render

them competitive.

The promise to do away with protection in ten years did not materialise.

Protection was continued under the Multi-Fibre Agreement, which was

once more scrutinised for phase-out under the Uruguay Round Agreement

of 1994. But even under that agreement, the phase-out of quotas was

back-loaded, with quotas on close to half of global textile trade kept

in place till January 1, 2005. It is well known that most developed

countries first lifted quotas on items of less relevance to developing

country trade, reserving true liberalisation till the beginning of 2005.

What the first-quarter surge in textile exports to the US indicates

is that despite 45 years of protection expressly justified by the need

to restructure the industry, the US has not done so, unlike countries

such as the UK whose dependence on textiles during the early stages

of their industrialisation was even greater. But the US is not the only

culprit. Even countries in the EU (such as France and Italy) are using

the US resistance to the Chinese export surge as the basis for a demand

for greater protection for their own textile production. The European

Union's trade commissioner, Peter Mandelson, has been resisting pressure

to impose restrictions on Chinese textile imports, on the grounds that

the available evidence of market disruption is inconclusive and could

not justify curbs for the time being. However, his ambivalent postures,

resulting from differences within the Community, suggest that the EU

too might resort to import curbs. Responding to calls from countries

like Sweden not to impose such curbs, since that would amount to protectionism,

Mandelson declared: We should not confuse protection with protectionism.

All this controversy arises despite efforts by China to dampen the growth

of its textile exports since January 2005 to temper the reaction to

likely export increases. In December 2004, China imposed export tariffs

of Rmb0.2-Rmb0.3 per item in some cases and Rmb0.5 per kilogramme in

others in response to concerns in the US and Europe that Chinese textile

exports might surge following the expiry of quotas on January 1. Now,

China is contemplating further export tariffs. Expectations are that

China might raise export tariffs by as much as Rmb2-Rmb4 per piece.

Such action is being contemplated despite the danger that Chinese exporters

are likely to be badly hit, because prices for garment orders are fixed

several months before shipment.

China's need to bend over backwards to placate the US results from three

factors. First, China's own dependence on the US market for exports

that have become a major engine for its growth. Second, the huge trade

and current account deficit on the US balance of payments, which is

resulting in a depreciation of the dollar and rising the spectre of

a financial crash and global recession. Third, the huge US trade deficit

with China that the former wants to reduce by getting China to revalue

its currency. The message is clear, if developing countries record a

deficit on their balance of payments it is their problem and a reflection

of their mismanagement. If the US records a deficit on it external account

that is everybody's problem and a reflection of a global “imbalance”

that needs correction.

Unfortunately, imposing curbs on Chinese textile imports into the US

or the EU may not resolve the problem either of unemployment in the

US and EU textile industries or the deficit on the US trade account.

It would merely serve to increase textile exports from other developing

countries to the US and EU. But the fact that this could be used to

divide developing country exporters and win the support from some of

them in the battle against China may suit the US and EU. It helps win

allies in the battle to force China to turn inwards rather than grow

on the basis of burgeoning exports. Globalisation is good only when

the US-and perhaps the EU-reaps its benefita. If that does not happen,

protectionism or voluntary export restraint is the preferred alternative.

© MACROSCAN 2005