A

noticeable feature of growth dynamics in contemporary

times is that investment and consumption spending

by households has been an important stimulus to growth.

Such spending, in turn, has been stimulated by changes

in the financial sector that have increased the volume

of credit, eased interest rates and made credit available

to individuals and firms that would have earlier been

considered inadequately creditworthy.

The last of these is of relevance, because it draws

into the market for housing and non-essential consumption

a set of consumers, who would not be present in these

markets if their spending was determined by their

current income. A credit boom expands the market for

certain assets and commodities at a much faster rate

than is possible if demand growth were dependent purely

on either income growth or on changes in income distribution.

Needless to say, income growth does matter in the

medium term, inasmuch as indebted households would

have to earn the incomes to meet the interest and

amortisation payments on their debt. If the requisite

increases in income do not materialise, defaults multiply

and this unwinds the boom. It would also have collateral

effects because it impacts on financial agents left

with non-performing debt and assets whose prices are

falling because of excess supplies of confiscated

assets on sale.

The US is an economy that now is experiencing such

a downturn, the full consequences of which are still

unclear. The housing market in the US has been crucial

to sustaining growth in the US ever since the dotcom

bust of 2000. Galloping housing purchases stimulated

residential investment and rising housing asset values

encouraged a consumption splurge, keeping aggregate

investment and consumption growing.

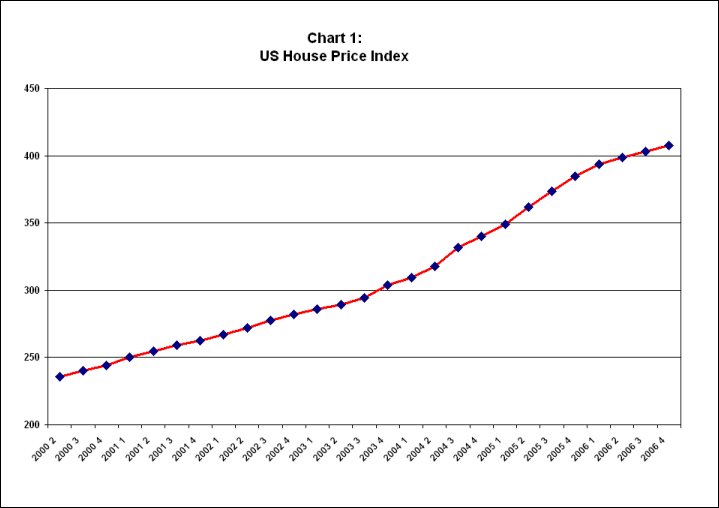

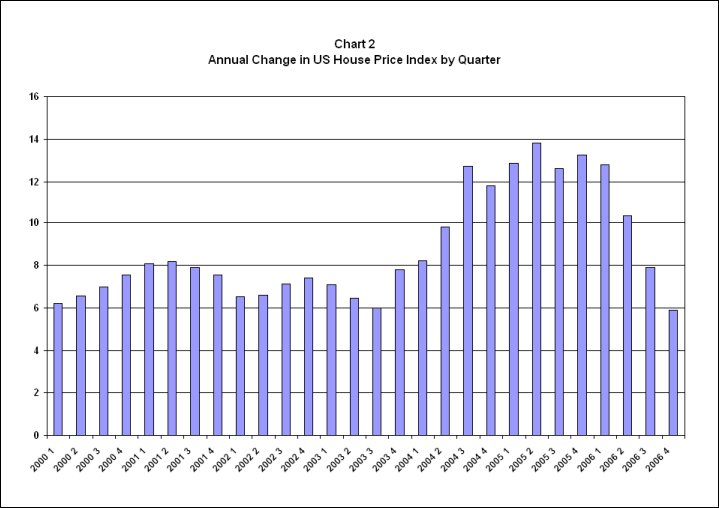

As Chart 1, which provides the quarter-wise annual

rate of change in the combined US House Price Index

shows, the housing market began experiencing a boom

in the middle of 2003, which peaked in mid-2005. Though

housing prices have continued to rise since then,

the annual rate of inflation has consistently declined

(Chart 2). This in itself may be a much needed correction

that should be welcome.

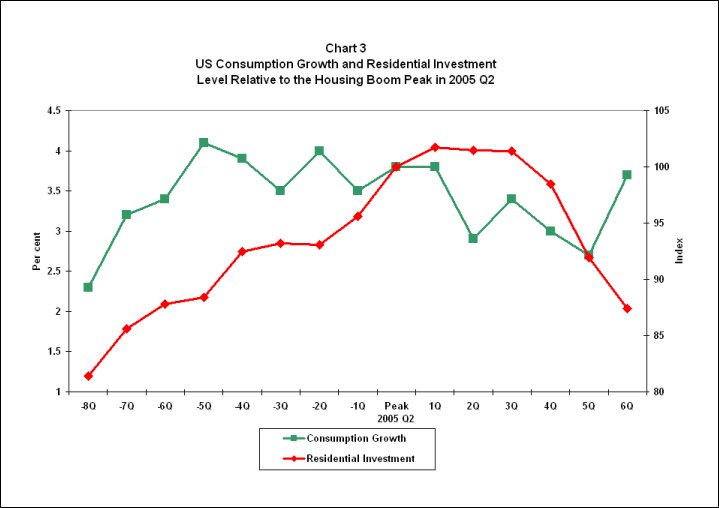

But the downturn is giving cause for concern for two

reasons. First, as mentioned earlier, growth in the

US economy has been sustained by the boom in housing.

Rising house values increases the wealth of home owners

and has a wealth effect that encourages debt-financed

consumption. This drives demand and growth. The housing

boom also pushes up residential investment and construction

which through the demands it generates and the employment

it creates helps accelerate growth. As Chart 3 shows,

these features seem to have played a role during the

current housing cycle as well, though the effect is

more noticeable in the case of residential investment

than consumption, where other factors too must have

played a role.

The second problem lies in the way in which the boom

was triggered and kept going. Housing demand grew

rapidly because of easy access to credit, with even

borrowers with low creditworthiness scores, who would

otherwise be considered incapable of servicing debt,

being drawn into the credit net. These sub-prime borrowers

were offered credit at higher rates of interest, which

were sweetened by special treatment and unusual financing

arrangements-little documentation or mere selfcertification

of income, no or little down payment, extended repayment

periods and structured payment schedules involving

low interest rates in the initial phases which were

"adjustable" and move sharply upwards when

they are "reset" to reflect premia on market

interest rates. All of these encouraged or even tempted

high-risk borrowers to take on loans they could ill

afford, either because they had not fully understood

the repayment burden they were taking on or because

they chose to conceal their actual incomes and take

a bet on building wealth with debt in a market that

was booming.

Chart

1 >> Click

to Enlarge

The default risk which was almost inevitable in this

kind of lending, increased sharply when interest rates

rose. The net result has been an increase in defaults

and foreclosures. The Mortgage Bankers Association

has reportedly estimated aggregate housing loan default

at around 5 per cent of the total in the last quarter

of 2006, and defaults on high-risk sub-prime loans

at as much as 14.5 per cent. With a rise in so-called

"delinquency rates", foreclosed homes are

now coming onto the market for sale, threatening a

situation of excess supply that could turn decelerating

house-price inflation into a deflation or decline

in prices. The prospect of such a turn are strong

given estimates by firms like Lehman Brothers that

mortgage defaults could total anywhere between $225

billion and $300 billion during 2007 and 2008.

The first casualties in the crisis have been the mortgage

lenders, who used borrowed capital to finance mortgage

lending. Firms like New Century Financial, WMC Mortgage

and others, which made huge returns during the boom,

expanded lending volumes, encouraged by low interest

rates and slowing house price inflation in 2006. This

required moving into the sub-prime market to find

new borrowers. Estimates vary, but according to one

by Inside Mortgage Finance quoted by the New York

Times, sub-prime loans touched $600 billion in 2006

or 20 per cent of the total as compared with just

5 per cent in 2001. These mortgages reflected very

little own equity of the borrower. According to Bank

of America Securities, loans to sub-prime borrowers

in 2001 covered on average 48 per cent of the value

of the underlying property. This had risen to 82 per

cent by 2006. According to the Financial Times, more

than a third of sub-prime loans in 2006 were for the

full value of the property.

Chart

2 >> Click

to Enlarge

Mortgage lenders or brokers were encouraged to do

this because they could easily sell their mortgages

to banks and the investment banks in Wall Street to

finance their activity and make a neat profit. And

the investment banks themselves were keen to buy into

the business because of the huge profits that could

be made by "securitising" these mortgages.

Firms such as Lehman Brothers, Bear Stearns, Merrill

Lynch, Morgan Stanley, Deutsche Bank, UBS and others

bought into mortgages, pooled them, packaged them

into securities and sold them for huge fees and commissions.

Numbers released by the Bond Market Association indicate

that mortgaged backed securities issued in 2003 were

at a peak in 2003 when they totalled $3 trillion.

Even though total values have declined since then

because of the deceleration in home price inflation,

they are still close to the $2 trillion mark. Among

the investors in these collateralised debt obligations

(CDOs) are European pension fund and Asian institutional

investors.

Chart

3 >> Click

to Enlarge

With high returns on creating these products and facilitating

trade in them, the investment banks were hardly concerned

with due diligence about the underlying risk associated

with these securities. That risk mattered little to

them since they were transferred to the purchasers

of those securities. The risks in the final analysis

are shared with pension funds and institutional investors

which were buying into these securities, looking for

high returns in an environment of low interest rates.

They are now experiencing a sharp fall in their asset

values and threatened with losses.

In fact the process of securitisation involves many

layers. To quote the Financial Times, the original

mortgages are "sold by specialist mortgage lenders

on to new investors, such as Wall Street banks, who

then use these to issue bonds which are often then

repackaged again as derivatives." According to

that paper, data from the Securities Industry and

Financial Markets Association indicate that more than

$2 trillion of mortgage-backed bonds were sold last

year, of which about a quarter were linked to sub-prime

mortgages. In sum, this whole process, which has at

the bottom home owners faced with foreclosure, is

driven by layers of financial interests looking for

quick profits or high returns. This has transformed

the mortgage securities business. In earlier times,

these securities were bought by investors who held

them till the loans matured and earned their returns

over time. Now these are marked to market and traded.

They are also use to create complex derivatives which

too are marked to market and traded.

The net result is that the housing market crisis threatens

to build into a crisis of sorts in the US financial

sector, resulting in a liquidity crunch that can aggravate

the slowdown and precipitate a recession. All this

has occurred also because of the regulatory forbearance

that has characterised the ostensibly "transparent"

but actually opaque markets that are typical of modern

finance. Investment banks did not reveal the weak

credit base on which the mortgage securities business

was built, investment analysts routinely issued reports

assuaging fears of a meltdown, credit rating agencies

did not downgrade dicey bonds soon enough, and the

market regulators chose to look the other way when

the speculative spiral was built.

But now that the crisis has struck, fingers are being

pointed at others by every segment of the business.

The first fall-person has been the ostensibly deceitful

home owner. "Liar-loans" in which the borrower

does not truthfully declare incomes is blamed by the

business for its crisis. But it takes little to prevent

such activity, if lenders actually want to. The Mortgage

Asset Research Institute, found from an analysis of

100 loans involving self-declared incomes that documents

those borrowers had filed with the IRS showed that

60 per cent of them had inflated their incomes by

more than half. It doesnít take much to demand an

IRS return when making a loan.

The investment banks are of course blaming the mortgage

lenders. Wall Street banks are filing suits to force

mortgage lenders to repurchase loans which they claim

were sold to them based on misleading information.

If a Wall Street bank can be tricked, they donít have

the right to advise investors where to put their money.

And reports have it that those who bought into the

bonds and derivatives these banks peddled are planning

to move court accusing these Wall Street firms of

failures of due diligence.

Finally, the regulators and Congress are sitting up,

as they did after the crash of the late 1990s which

led to the passing of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act. US Congressmen

are threatening to frame a law that restricts the

freedoms investment banks and other financial entities

have when creating bonds and derivatives by repackaging

mortgages to sell them to investors around the world.

But all this is to wake up after the event has transpired.

The "efficient" American financial system

is clearly not geared to preventing a crisis, even

if it proves capable of finding a solution. A solution

that prevents the sub-prime crisis from overwhelming

the mortgage business as a whole, by triggering a

collapse in house prices, is imperative given the

importance of the housing boom in keeping the American

economy going. A slowdown in growth may be manageable.

But a recession can send ripples across the globe.

All this has lessons for countries like India. First,

they should be cautious about resorting to financial

liberalisation that is reshaping their domestic financial

structures in the image of that in the US. That structure

is prone to crisis, as the dotcom bust and the current

crisis illustrates. Second, they should refrain from

over-investing in the doubtful securities that proliferate

in the US. Third, they should opt out of high growth

trajectories driven by debt-financed consumption and

housing spending, since these inevitably involve bringing

risky borrowers into the lending and splurging net.

Finally, they should beware of international financial

institutions and their domestic imitators, who are

importing unsavoury financial practices into the domestic

financial sector. The problem, however, is that they

may have already gone too far with processes of financial

restructuring that have increased fragility on all

these counts.