It

has been more than four years since the onset of the

financial crisis and the accompanying Great Recession

in the US and much of the developed world. Yet, the

crisis is still with us. It has only spread geographically,

with its worst consequences now visible in the peripheral

countries of Europe rather than in the financial centres

of the world where it originated.

Early into the crisis, its severity had resulted in

a near-consensus on the need to re-regulate finance.

The financial and real economy collapse was too close

to the experience of the 1930s to brook further delay

in rethinking the deregulation that is now widely

seen as having contributed to these developments.

There was need for a response that equalled in scope

the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933. How much has been

achieved in the last four years and more? Not much

in Europe, where despite the de Larosière report,

the focus remains on stalling and reversing the ongoing

crisis rather than on preventing future crises. If

financial reform has proceeded anywhere it is in the

US. It began with the Obama Statement of June 2009

on the way forward and culminated in the passage of

the Dodd Frank Act. As a result, efforts are now on

to formulate a set of rules regulating the varied

sets of markets, institutions, activities and instruments

that constitute the complex financial structure that

evolved as a result of financial deregulation. Unfortunately,

the experience till now has been that, while much

was promised, little progress is being achieved.

From the very beginning it became clear that the discussion

on reform in the US was riven by the tension between

those fighting to restrict the response largely to

bailing-out finance and those who were demanding a

return to strong regulation of the pre-1980s kind.

A hint that the actual regulatory package that would

get implemented would include significant compromises

in favour of Finance Capital came early, with the

Obama package. While declaring that the economic downturn

was the result of ''an unravelling of major financial

institutions and the lack of adequate regulatory structures

to prevent abuse and excess,'' the Obama statement

did not blame the dismantling of the regulatory regime

that was put in place in the years starting 1933 for

these developments. It attributed them to the fact

that ''a regulatory regime basically crafted in the

wake of a 20th century economic crisis-the Great Depression-was

overwhelmed by the speed, scope, and sophistication

of a 21st century global economy.'' The problem was

not that the Glass-Steagall Act was diluted and dismantled,

but that it had lost its relevance.

Implicit in this was the understanding that there

was no question of reversing the dismantling of the

regulatory walls that separated different segments

of the financial sector or of restrictions set on

institutions and agents in individual segments, especially

banking. Other ways, which take account of the changes

in the world of finance, had to be found to rein in

the tendency of the financial sector to proliferate

risk and create conditions for a systemic failure.

Especially because of the externalities involved for

the functioning of the real economy, which required

using taxpayers' money to rescue the system.

Despite this moderation, there were a number of important

regulatory advances that the Obama package, released

as a trial balloon, incorporated. To start with, it

recognised the role played by institutions-banks and

non-banks-that are too big to fail (TBTFs) in the

events leading up to and after the crisis, because

they were systemically important financial institutions

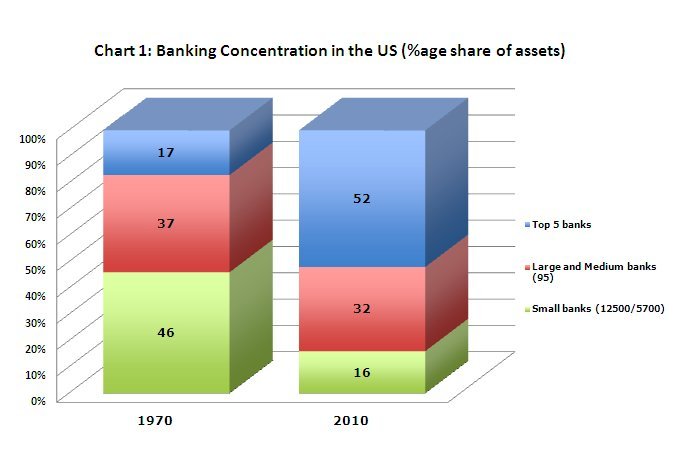

(SIFIs). The top 5 banks, which accounted for just

17 per cent of commercial banking assets in 1970,

held 52 per cent of those assets in 2010 (Chart 1).

Chart

1 >>

(Click to Enlarge)

It

hardly bears emphasising that these entities are not

just large in size, but because the walls between

different segments of the financial sector (conventional

banking, investment banking, insurance, etc) were

completely dismantled by 1999, they are diversified

as well. Further, as the Dallas Fed's report notes,

size was built not on equity but on leverage, leading

to a combination of little capital, much debt and

too much risk. Also with size came complexity, and

with complexity came obfuscation. These consequences

of the search for quick and large profits increased

the importance of a few institutions as well as rendered

them prone to failure. But their failure would have

ripple effects across the financial sector and as

a corollary impact adversely on the real economy.

And since for this reason they could not be allowed

to fail, the cost of ensuring their survival had to

be transferred onto the taxpayer. This was what was

done when the crisis occurred, with the state rushing

to the assistance of most large financial firms. As

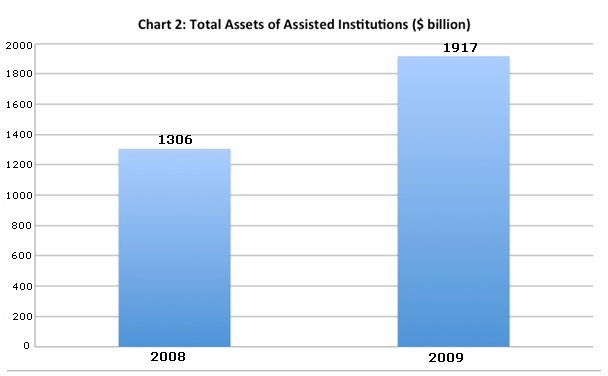

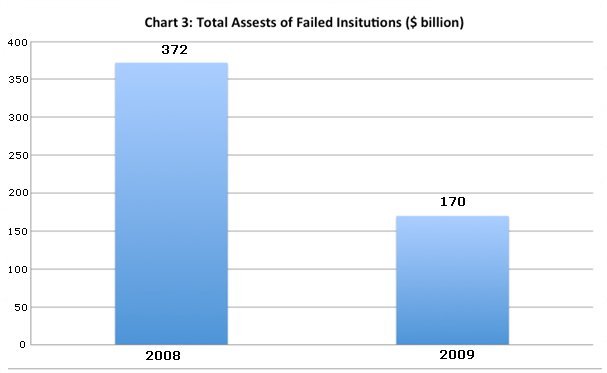

Charts 2 and 3 show, the assets of institutions that

were assisted to survive during 2008-09 amounted to

$3.22 trillion, where many multiples of the assets

of those that were allowed to fail, which stood at

just $542 million. Much of the financial system was

kept in place with aid from the state.

Chart

2 >>

(Click to Enlarge)

It must be noted that what is at issue here is not

size per se. It is the ''excessive'' size of privately

owned institutions that was the result of speculative

practices aimed at garnering quick profits and permitted

and encouraged by deregulation. Large publicly owned

banks and specialised financial institutions would

not be driven by the same objectives and can exploit

economies of scope to deliver important developmental

benefits.

However, the Dallas Federal Reserve is critical of

size because (i) the need to rescue them left most

Americans with the impression that ''economic policy

favours the big and well-connected'', which is not

good for the policy maker; and (ii) even this massive

transfer of resources has not recapitalised these

institutions adequately and restored normal credit

provision by them. With banks holding back on providing

credit, the Fed's efforts at stimulating a recovery

with a combination of quantitative easing and low

interest rates are not proving very successful. The

irresponsibility of the banks, argues the report,

has undermined the efficacy of monetary policy and

therefore of the Federal Reserve.

Despite this partisan perspective, the Dallas Fed

does underline the fact that little is being done

to address the problem that flows from having privately

managed TBTFs. The Obama package promised a new role

for the Federal Reserve in overseeing and regulating

these entities as well as measures to trim their size.

Discussions on these and other proposals, running

parallel to investigations on the developments that

led up to the crisis in 2007, resulted in the bill

introduced by senators Barney Frank and Chris Dodd,

and finally passed in revised form and signed into

law in July 2010. Since then a number of agencies

such as the Federal Reserve, the Treasury, the Federal

Deposit Insurance Agency and the SEC have been engaged

in a long and slow process of converting the provisions

of the Act into implementable rules and regulations.

The results have thus far been disappointing.

Chart

3 >>

(Click to Enlarge)

The Dodd-Frank Act itself is on occasion disappointing

as in the case of TBTFs. Under the Act these institutions

would be monitored and regulated by a newly established

Financial Stability Oversight Council, which would

''bring together regulators from across markets to

coordinate and share information; to identify gaps

in regulation; and to tackle issues that don't fit

neatly in an organisational chart.'' They would also

be subject to more stringent regulations with regard

to capital adequacy and liquidity. However, all this

amounts to an effort to prevent the emergence of institutions

that are considered too important to fail, but to

prevent the failure of large firms without having

to burden the taxpayer. Since it is impossible to

guarantee that this would work at all times, an effort

has been made to devise a system that would allow

firms to be unwound without damage to the system and

excessive burdens on the tax payer.

This, the Dallas Fed, feels is both unconvincing and

unlikely to succeed, and would not serve to restore

faith in ''the system of market capitalism'' based on

competition. It is, therefore, in favour of ''the ultimate

solution for TBTF-breaking up the nation's biggest

banks into smaller units.'' While this position is

controversial, its source and content reflect the

more widespread perception that the opportunity for

reform is being lost. In fact, the too big to fail

issue is not the only one where disappointment is

rife. Another, for example, is the need for some form

of structural regulation that seeks to limit or circumscribe

the activities of the all-too-important banking system.

Under Glass-Steagall this was essentially achieved

by segmenting the financial sector into (i) institutions

that were depository institutions (accepting deposits

from the public at large), which were subject to membership

of the deposit insurance system and were eligible

for liquidity support from the central bank or the

lender of last resort; and (ii) other institutions

including those which accepted investments from high

net worth individuals that were not insured and which

were not eligible for central bank accommodation.

While for a number of reasons a return to this system

was not seen as advisable, the need to limit the activities

of prime depository institutions so as to keep them

out of sensitive sectors involving speculative operations

was recognised by many. Over time those holding this

view gravitated to the ''Volcker rule'' as representing

the minimum acceptable level of separation of activities

between institutions in the financial sector.

The stated objective of the Volcker rule is to ''generally

prohibit any banking entity from engaging in proprietary

trading or from acquiring or retaining an ownership

interest in, sponsoring, or having certain relationships

with a hedge fund or private equity fund (''covered

fund''), subject to certain exemptions.'' Proprietary

trading involved engaging as the principal for any

account used to take positions in securities with

the intention of selling it in the near-term for profit.

Implicit in it was the idea that while separation

of activity could not be complete, since it allowed

banks to serve as agent, broker or custodian for an

unaffiliated third party, banks should not be allowed

to use their own funds, especially those obtained

from depositors, to trade in securities. Besides restricting

banks from engaging in risky activities using depositors'

monies, the proposal was addressing the moral hazard

that arises when bank managers were allowed freedom

in a context where deposits were insured and there

was an implicit guarantee against failure.

This is one area where the Fed, FDIC and SEC have

sat together and attempted to formulate the guidelines

to implement the version of it incorporated in the

Dodd-Frank Bill (DFB). What is striking is the number

of exemptions that have been made with regard to the

proscription on proprietary trading by bank holding

companies (BHCs). The first major set of exemptions

relates to the activities of underwriting or market

making. The rule now permits banks to continue with

the activity of underwriting share issues for clients,

even though that would result in the bank acquiring

equity in instances where under-subscription leads

to shares devolving on the underwriter. Similarly,

by serving as a market maker who stands by with a

bid and an ask price for equities, a bank may find

itself in a situation where it is acquiring stocks

that it cannot find an immediate buyer for, but in

time makes a profit selling it at a significantly

higher price. To distinguish between these activities

and proprietary trading is to draw a fine line, which

can be erased when banks choose to circumvent the

rule. Implementing the rule in practice would, therefore,

prove difficult.

A similar approach is adopted with regard to ''permitted

risk-mitigating hedging activities''. In particular,

by focusing on reining in short-term trading and implicitly

permitting longer-term arbitrage, the rules as framed

may be leaving the door open for the rogue trade.

Finally, the Volcker Rule provides for ''permitted

trading on behalf of customers.'' To that end it identifies

''categories of transactions that, while they may involve

a banking entity acting as principal for certain purposes,

appear to be on behalf of customers within the purpose

and meaning of the statute.'' In sum, the proposed

rules are ambiguous enough to allow banks to circumvent

the law and engage in proprietary trading in some

form.

This too is an example of how, as ideas get translated

into implementable decisions, through the rough-and-tumble

of debate and politics, we are ending up with limited

progress on addressing the failure of regulation that

resulted in the outbreak of the 2007 crisis with its

damaging external effects on the real economy. The

Dallas Fed is also pointing to that danger.

*This

article was originally published in the Business Line

on 2nd April, 2012