Statistics

on the global production and trade in software are

notoriously inconsistent, because of difference in

coverage and methodology. Any single source can at

most provide an indication of the structure of and

trends in the industry, rather than an exact measure

of its size.

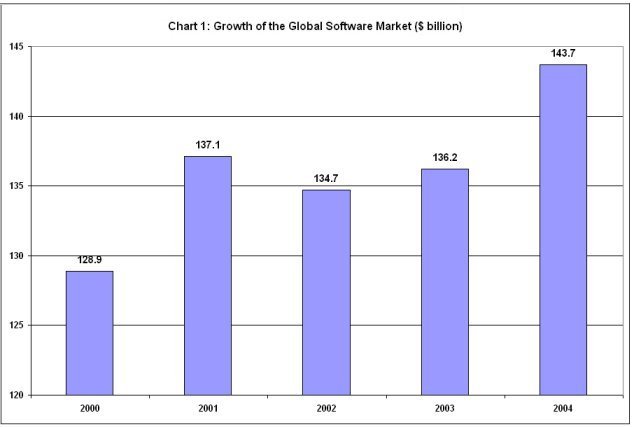

According to leading market research firm Datamonitor,

the global market for software totalled $143.7 billion

in 2004 (Chart 1). The interesting feature is, of

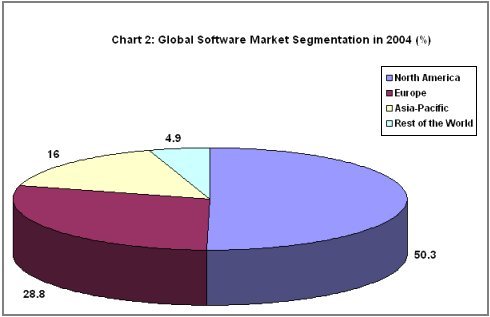

course, the structure of this market. In terms of

market segments the North American market clearly

dominates, accounting for slightly more than 50 per

cent of the total. Europe is a distant second (28.8

per cent) followed by the Asia-Pacific (16 per cent)

and the rest of the world (4.9 per cent) (Chart 2).

Chart

1 >> Click

to Enlarge

A large home market, among other things, has served

the US industry well. It dominates the global trade

in software as well. As Table 1 indicates the US has

accounted for a quarter to a half of global trade

in one area (packaged software) for which figures

are available in the UN's commodity trade database.

Chart

2 >> Click

to Enlarge

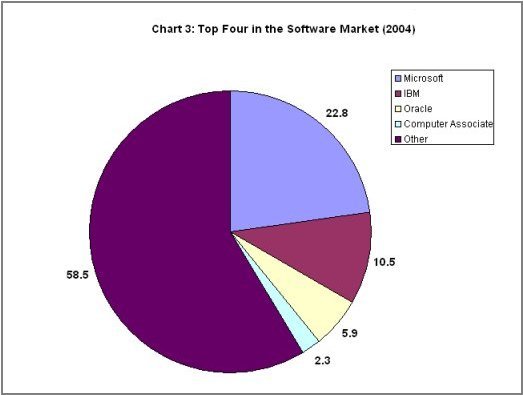

The industry is also highly concentrated in terms

of market shares of leading firms, with US firms dominating

the market. The top four firms (Microsoft, IBM, Oracle

and Computer Associates), accounting for 41.5 per

cent of the global market, are from the US (Chart

3). This structure belies the conventional notion

that the software sector is characterised by extremely

low barriers to entry.

Reporter

Title |

Trade

Value

|

Market

Share |

USA |

$4,549,548,849 |

27.3% |

Germany |

$2,644,021,184 |

15.8% |

Ireland |

$1,833,543,792 |

11.0% |

UK |

$1,533,462,785 |

9.2% |

EU-25 |

$1,282,913,411 |

7.7% |

Other |

$6,123,007,968 |

36.7% |

Total

Export |

$16,683,584,578 |

100.0% |

Table

1 >> Click

to Enlarge

The software sector is seen by many as characterised

by low costs of entry and an easily accessed and almost

universally available knowledge-base for innovation.

What is of special significance is that the sources

of this knowledge, such as journals, conferences,

seminars and publicly or privately financed training

programmes, are easily accessed. This makes it easy

for wholly new entrants to acquire the knowledge base

required for cutting edge technological contributions

to the industry, as was and is true of at least some

of the myriad start-ups in Silicon Valley. Thus, the

software sector is seen as one where knowledge is

easily acquired and innovations easily replicated,

requiring skilled labour but little by way of capital

investment.

This perception of the industry fails to take account

of the heterogenous nature of the industry which has

added on different segments in the course of its evolution,

driven by technological changes in hardware that have

created new demands and opportunities. Writing in

1995 Martin Campbell-Kelly classified software firms

into three distinct sectors, based on their historical

evolution: software contractors, and the personal

computer software industry. The role of software contractors

was to develop one-of-a-kind programs for computer

users and manufacturers, buying and selling expensive

computer systems with limited capabilities by today's

standards. Packaged software producers emerged in

the 1980s attempting to provide standard software

for applications needed by specific sets of clients.

These two sets of software firms either served or

competed with hardware firms, who sought to develop

software applications for purchasers of their equipment.

They were part of the computer industry establishment.

Chart

3 >> Click

to Enlarge

It was for this reason that Campbell-Kelly chose to

treat producers of software for personal computer

users as a distinct category, even though they were

involved in the same kind of business as the packaged

software producers. In his view producers of personal

computer software were in the business of generating

products that would have a large number of users,

if successful, and consisted of many firms that were

outside the traditional software establishment.

Since then software contractors (including relatively

small firms) and hybrid firms like IBM have developed

into service companies providing enterprise software,

systems integration and consultancy services to large

corporations, adding a major software services component

to the industry. However, the evidence seems to suggest

that the structure of the US software industry has

not changed very much over time.

Further, the evidence suggests that the market for

large scale public and private projects were characterised

by significant barriers to entry, with established

firms and a few successful start-ups that grew rapidly

in size dominating the market. However, entrepreneurial

firms always had a place in the industry, providing

custom programs and software maintenance services

of modest scale to medium-sized firms. According to

one estimate there were 2800 software contractors

in the US in 1967, many of whom were small firms catering

to smaller clients. In this market, the only barriers

to entry were programming knowledge, technical knowledge

of the applications domain and the availability of

a client.

With the growth of the market for packaged software

in the wake of IBM's decision to unbundle software

and hardware in 1968, it would appear that smaller

firms would have a new market. But in actual fact

the need to develop a product fully, by investing

a substantial number of programming man-hours, before

testing it and entering the market increased sunk

costs substantially. This was in itself a barrier

to entry. And, though the arrival of the personal

computer increased the scope for packaged software

substantially, the problem of high sunk costs remained.

As has been repeatedly noted, producing the first

unit of a software product requires large investments

in its generation, whereas producing an additional

unit is almost costless. The larger the sales, therefore,

the lower the average cost and the higher the return.

But that is not all. When large sales imply a large

share of the market as well, scale becomes a means

of ensuring consumer loyalty and strengthening oligopolistic

positions. This is the result of ''network externalities''

stemming from three sources. First, consumers get

accustomed to the user interface of the product concerned

and are loath to shift to an alternative product which

involves some ''learning'' before the features of

the product can be exploited in full. Second, the

larger the number of users of a particular product,

the greater is the compatibility of each user's files

with the software available to others, and greater

the degree to which files can be shared. The importance

of this in an increasingly networked environment is

obvious. Finally, all successful products have a large

number of third-party software generators developing

supporting software tools or ''plug-ins'', since the

applications program interface of the original software

in question also becomes a kind of industry standard,

increasing the versatility of the product in question

without much additional cost to the supplier. These

''network externalities'' help suppliers of a successful

software package to ''lock-in'' consumers as well

as third party developers and vendors, leading to

substantial barriers to entry.

Partly because of these characteristics successful

start-ups like Microsoft, which entered the market

at the right time, came to dominate the industry.

As a result, even though the history of Silicon Valley

is full of anecdotes of tech-savvy entrepreneurs discovering

new possibilities and new products, concentration

is the dominant feature, with most start-ups with

innovative products now being acquired rather early

in their history.

The reasons for this need to be spelt out. Take the

case of software products for mass use. Creating such

a product starts with identifying a felt need (say,

for a browser once the internet was opened up to the

less computer savvy or for a web-publishing programme

once the internet went commercial). The persons/firms

identifying such a need must work out a strategy of

generating the product, by hiring software engineers,

at the lowest cost in the shortest possible time.

Once out, the effort must be to make the product a

proprietary, industry standard. This involves winning

a large share of the target consumers, so that the

product becomes the industry standard in its area.

Once done, the product becomes a revenue generating

profit centre.

The investment required is the sums involved in setting

up the company, in investing in software generation

during the gestation period, and in marketing the

product once it is out so as to quickly win it a large

share of the market. Needless to say, while entry

by individuals or small players are not restricted

by technology, they could be limited by the lack of

seed capital. This is where the venture capitalists

enter, betting sums on start-ups which if successful

could give them revenues and capital gains that imply

enormous returns.

There are, however, three problems here. The first

is one of maintaining a monopoly on the idea during

the stage when the idea is being translated into a

product. The second is that of ensuring that once

the product is in the public domain competitors who

can win a share of the market before the originator

of the idea consolidates her position do not replicate

it. It is here that a feature of 'entrepreneurial

technologies' – the easy acquisition and widespread

prevalence of the knowledge base needed to generate

new products - considered an advantage for small new

entrants actually proves a disadvantage. Thirdly,

no software product is complete, but has to evolve

continuously over time to offer more features, to

exploit the benefits of increasing computing power

and to keep pace with developments in operating systems

and related products. Thus large and financially strong

competitors, even if they lag in terms of introducing

a product 'replica', can in time lead in terms of

product development, and erode the pioneer's competitive

advantage.

There are two aspects of technology that are crucial

in this regard. First, their source. Second, the appropriability

of the benefits of a technology. As mentioned earlier,

in the case of software the sources were in the public

domain. This was where the advantage lay for the small

operator. But once a technology is generated based

on some expenditure in the form of sunk costs, there

must be some way in which the innovator can recoup

these costs and earn a profit as incentive to undertake

the innovation. In the Schumpeterian world this occurred

because of the 'pioneer profits' that the innovator

obtained. The lead-time required to replicate a technology

itself provides the original innovator with a monopoly

for a period of time that generates the surplus which

warrants innovation.

Most often this alone is not enough to warrant innovation

and in the software sector lead times can be extremely

low, especially if the competitor invests huge sums

in software generation, reducing the lead-time substantially.

It is for this reason that researchers have defended

and invoked the benefits of patents, copyright and

barriers to entry in production, which allow innovators

to stave off competition during the period when sunk

costs are being recouped. Unfortunately, neither is

the status of patents and copyrights in the software

area clear (as illustrated by the failure of Apple

to win proprietary rights over icons in user interfaces),

nor are there barriers to entry into software production.

This has had two implications. First, the importance

of secrecy in the software business. The 'idea' behind

the product must be kept secret right through the

development stage, if not competitors can begin rival

product developments even before the original product

is in the market. A feeble attempt to institutionally

guarantee such secrecy is the now infamous 'non-disclosure

agreements' which prospective employees, financiers

and suppliers are called upon to sign by the innovator

who is forced to partially or fully reveal his idea.

Secondly, even after the product is out, since the

threat of replication remains, it is necessary to

strive to sustain the monopoly that being a pioneer

generates. This is where the possibility of locking

in users with the help of an appropriate user interface

which they become accustomed to and are reticent to

migrate away from, and locking in producers of supportive

software with an appropriate 'applications programming

interface' becomes relevant. It should be obvious

that sustaining monopoly to recoup sunk costs can

indeed be difficult.

Such strategies did help the early start-ups, resulting

in the jeans-to-riches stories (Microsoft, Netscape,

etc.) with which Silicon Valley abounds. But more

recently it has become clear that start-ups undertake

innovative activities only to create winning products

that the big fish acquire. This is because of the

possibility of easy replication and development of

an original product, which can be done by dominant

firms with deep pockets that allow them to stay in

place and spend massively to win dominant market shares.

In the event, the likelihood that a small start-up

would be able to recoup sunk costs, clear debts and

make a reasonable profit is indeed low. Selling out

ensures that such sums can indeed be garnered. And

selling out is often a better option than investing

further sums in developing the product, now faced

with a competitive threat, in keeping with industry

and market needs.

Given this feature of the software products market,

it is not surprising that small players (such as Netscape

with it Navigator and Vermeer Technologies that delivered

Frontpage) are mere transient presences in key areas

even in the developed countries. To expect developing

country producers to fare better is to expect far

too much. The latter can merely be software suppliers

or outsourcers for the dominant players.

In sum, other than in the supply of services to medium-sized

firms or serving as contractors for relatively small

projects by industry standards or serving as sub-contractors

to leading software contractors, the basic nature

of the software sector seems to be such that concentration

is the key.

This is a factor that firms from countries like India

have to confront when attempting to exploit the benefits

of their pool of skilled cheap labour. India has been

successful in breaking into this sector. But that

success is also predicated on having an extremely

concentrated industry here. Thus a recent study of

65 small and medium enterprises in the IT sector (B.G.

Shirsat, Business Strandard, July 14 2006), with revenues

ranging from Rs.10 crore to Rs.200 crore, found that

their revenues in 2005-06 amounted to Rs.3,400 crore,

which was just 8.9 per cent of the Rs.38,169 crore

revenue garnered by the top four IT firms (TCS, Wipro,

Infosys Technologies and Satyam Computer). Their profits

aggregated Rs 575 crore or 6.9 per cent of the Rs.8,386

crore earned by the top four. This concentrated structure

is sustained either through the acquisition of smaller

firms or by the exit from the industry because of

unviability. This has implications for policies aimed

at ensuring the proliferation of software firms as

part of India's ongoing IT thrust.