Themes > Features

01.08..2008

Balance of Payments: Do We Need to Worry?

It

has been some time now since the government has stopped bothering too

much about the balance of payments. Indeed, the continuous and even excessive

build-up of foreign exchange reserves (which now stand at more than $310

billion, making India’s holding the fourth largest in the world) suggests

that the problem may be one of plenty rather than scarcity, far removed

from the days when the foreign exchange constraint was seen as binding

upon domestic economic growth.

This has led to an attitude of complacency, not only among policy makers but even among the wider public, whereby balance of payments issues are rarely taken as potential problems. It is even common to hear the argument that the best way to manage the current inflation within the country is simply to liberalise imports further, on the assumption that our foreign exchange situation is presently quite comfortable. Yet this argument is flawed not only because it ignores the potential damage to domestic activity and employment from more imports, but because it underestimates the fragility of recent tendencies in the balance of payments.

In fact, there are several sources of concern in the recent pattern of external payments. The build-up of reserves has been led by substantial inflows in the capital account, which are either debt-creating or inherently short-term and speculative in nature. And this has been accompanied by the emergence and increase in current account deficits, which make India’s foreign reserve accretion fundamentally different from and more problematic than it is in other countries with large reserves, such as Japan and China.

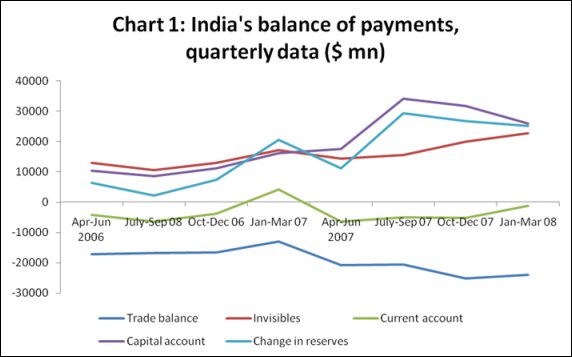

For much of the past decade, India’s current account was in surplus, because the trade deficits were more than compensated by substantial increases in remittances from workers abroad and software exports. However, in recent years deficits have emerged, largely because of the significant growth in trade imbalance. In the past two years, as Chart 1 shows, the current account has been in deficit in almost every quarter, and the imbalance has widened sharply in 2007-08.

This has led to an attitude of complacency, not only among policy makers but even among the wider public, whereby balance of payments issues are rarely taken as potential problems. It is even common to hear the argument that the best way to manage the current inflation within the country is simply to liberalise imports further, on the assumption that our foreign exchange situation is presently quite comfortable. Yet this argument is flawed not only because it ignores the potential damage to domestic activity and employment from more imports, but because it underestimates the fragility of recent tendencies in the balance of payments.

In fact, there are several sources of concern in the recent pattern of external payments. The build-up of reserves has been led by substantial inflows in the capital account, which are either debt-creating or inherently short-term and speculative in nature. And this has been accompanied by the emergence and increase in current account deficits, which make India’s foreign reserve accretion fundamentally different from and more problematic than it is in other countries with large reserves, such as Japan and China.

For much of the past decade, India’s current account was in surplus, because the trade deficits were more than compensated by substantial increases in remittances from workers abroad and software exports. However, in recent years deficits have emerged, largely because of the significant growth in trade imbalance. In the past two years, as Chart 1 shows, the current account has been in deficit in almost every quarter, and the imbalance has widened sharply in 2007-08.

Chart

1 also shows the very significant role played by net invisibles, which

have been growing continuously in almost every quarter. The trade balance,

by contrast, has been deterioriating, and quite sharply after April

2007. This has led to a trade deficit for the entire financial year

2007-08 of more than $90 billion. The increase in net invisibles has

not been enought to counteract this, so that the total current account

deficit for the year was $17.4 billion. By the last quarter of 2007-08,

this meant that the current account deficit amounted to 1.6 per cent

of GDP, and the trade deficit alone amounted to 8.4 per cent of GDP!

This is the trade deficit based on the RBI’s figures, which are quite different from the commercial data released by the DGCI&S. Indeed, the difference between the import data from the two sources has grown from $5.5 bn in 2006-07 to $12.8 bn in 2007-08. This is largely because the RBI data include some imports made by government (including of defence equipment and the like) that do not go through the customs process and are therefore not recorded by the DGCI&S.

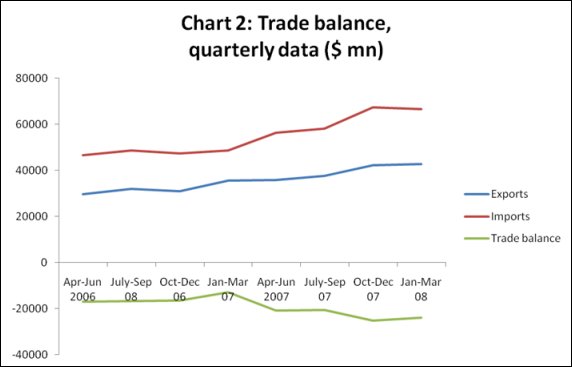

The worsening of the trade balance has been rapid after March 2007, as indicated in Chart 2. This is essentially because of a sharp acceleration in imports, since exports continued to grow at more or less the same rate as before. Over the year, exports increased (in dollar terms) by 24 per cent but imports increased by 30 per cent.

This is the trade deficit based on the RBI’s figures, which are quite different from the commercial data released by the DGCI&S. Indeed, the difference between the import data from the two sources has grown from $5.5 bn in 2006-07 to $12.8 bn in 2007-08. This is largely because the RBI data include some imports made by government (including of defence equipment and the like) that do not go through the customs process and are therefore not recorded by the DGCI&S.

The worsening of the trade balance has been rapid after March 2007, as indicated in Chart 2. This is essentially because of a sharp acceleration in imports, since exports continued to grow at more or less the same rate as before. Over the year, exports increased (in dollar terms) by 24 per cent but imports increased by 30 per cent.

It

is often believed that the rapid growth of imports in 2007-08 was essentially

because of the dramatic increase in oil prices, which naturally affected

the aggregate import bill. Certainly this played a role, but some non-oil

imports also increased rapidly. Therefore, while oil imports in the last

quarter of 2007-08 were 89 per cent higher (in US dollar terms) than in

the same quarter of the previous year, non-oil imports were also higher

by 31 per cent.

Table 1 provides an idea of the commodity categories that were the main drivers of export and import growth over the past year. The most rapid growth of exports was for agricultural commodities, which is a circumstance with both positive and negative features. The export of engineering goods was also quite rapid, as were exports of gems and jewellery and chemicals. Agricultural goods were dominantly exported to West Asia, whereas engineering goods and ores and minerals were increasingly exported by India to China.

Table 1 provides an idea of the commodity categories that were the main drivers of export and import growth over the past year. The most rapid growth of exports was for agricultural commodities, which is a circumstance with both positive and negative features. The export of engineering goods was also quite rapid, as were exports of gems and jewellery and chemicals. Agricultural goods were dominantly exported to West Asia, whereas engineering goods and ores and minerals were increasingly exported by India to China.

Table

1:

Important Trade Items in 2007-08 |

||

Share %

|

Growth %

|

|

|

Exports |

||

| Engineering goods |

20.91 |

11.65 |

| Petroleum products | 15.64 | 18.46 |

| Gems & Jewellery | 12.36 | 9.47 |

| Chemicals & related products | 13.63 | 4.71 |

| Textiles | 11.38 | -2.08 |

| Agriculture & allied products | 8.43 | 37.16 |

| Ores & minerals | 5.66 | 14.42 |

| Leather & leather goods | 2.16 | 1.21 |

| Electronic goods | 2.11 | 1.48 |

|

Imports |

||

| Petroleum products | 32.75 | 34.97 |

| Machinery | 13.81 | 23.94 |

| Electronic goods | 8.55 | 27.77 |

| Gold | 7.08 | 17.5 |

| Iron & steel | 3.53 | 41.12 |

| Pearls, precious & semi-precious stones | 3.33 | 6.59 |

| Transport equipment | 3.07 | 65.31 |

| Organic chemicals | 3.05 | 32.83 |

|

Source: DGCI&S |

||

Two items of exports deserve special mention. First, the export of petroleum products has increased rapidly from 2005 when domestic private refining companies were first allowed to export, and last year amounted to more than 15 per cent of the total value of exports. Such exports (mainly of high-speed diesel, motor spirit and other light oils and preparations) are dominated by one private refiner, and interestingly the UAE and Singapore have emerged as the major markets for this. Second, textiles and textile products, which were earlier among the more dynamic exports, actually declined in value over the past year, reflecting the increased competitive pressure from other developing countries, especially China, in the phase after the removal of the Multi-Fibre Arrangement.

Table 1 makes it clear that petroleum products were not the only rapidly increasing imports. While aggregate imports grew in value by 30 per cent over the year, oil imports increased by 35 per cent. But the import of transport equipment (including motor vehicles) increased by 65 per cent, of iron and steel by 41 per cent and of organic chemicals by 33 per cent. Even machinery and electronic goods imports increased rapidly, reflecting the domestic investment and middle class consumption booms.

Table

2: Major Trading

Partners

in 2007-08 |

||

Share %

|

Growth %

|

|

|

Exports |

||

| USA | 13.02 | -2.37 |

| UAE | 9.66 | 13.62 |

| China | 6.78 | 15.66 |

| Singapore | 4.31 | 0.46 |

| UK | 4.14 | 4.21 |

|

Imports |

||

| USA | 11.3 | 37.99 |

| UAE | 8.1 | 28.98 |

| China | 5.62 | 38.44 |

| Singapore | 5.51 | 0.08 |

| UK | 4.58 | 28.15 |

|

Source: DGCI&S |

||

These commodity-wise trends were mirrored in the direction of trade. The most significant tendency was the continuing decline in the importance of the USA in India’s merchandise trade. Exports to the US actually declined US dollar terms, and imports from the US barely increased. As a result, by the last quarter of 2007-08, China had emerged as the largest trading partner for India, with imports from that country significantly outpacing exports to it. As is evident from the import data, the increase in non-oil imports by India was dominated by China. The UAE and Saudi Arabia have become important in intra-industry trade in petroleum products, as noted above.

While merchandise trade may show a large imbalance, in the past the surplus on invisibles has generally been large enough to make the current account positive or in very small deficit. This was generally because of two important inflows: the receipts from exports of software services, which include many IT-enabled services such as Business Process Outsourcing, and remittances from Indian workers abroad which come in as private transfers.

Table

3:

Invisible Payments

in 2007-08, $ mn |

|||

|

Credit |

Debit

|

Net | |

| Total Services | 87,687 | 50,137 | 37,550 |

| Software Services | 40,300 | 3,249 | 37,051 |

| Business Services | 16,624 | 16,668 | -44 |

| Other Services | 30,763 | 30,220 | 543 |

| Private Transfers | 42,589 | 1811 | 40,778 |

| Investment Income | 13,799 | 19,038 | -5,239 |

| Travel | 11,349 | 9,231 | 2,118 |

|

Source: RBI |

|||

However, in 2007-08, while these inflows remained large, there are other indications that invisible payments cannot be counted upon to finance the trade deficit to the same extent in future. Thus, while software exports remained buoyant, they are unlikely to remain unaffected by the slowdown in the major market, the US, in the current year.

However, private transfers are more complex. That part of remittances which is from the US may be adversely affected, but the rise in oil prices in imparting new dynamism to oil-exporting West Asian countries where most Indian workers abroad currently reside.

Inward remittances amounted to nearly $43 bn in 2007-08, increasing by 47 per cent over the previous year. They were almost equally divided between inward remittances for family maintenance, and local withdrawals or redemptions from NRI deposits. In 2007-08, the inflows and outflows under NRI deposits were almost the same. But a growing proportion of withdrawals from NRI deposits are repatriated, rather than used within the country. This ratio increased from 15 per cent of total withdrawals in 2006-07 to 35 per cent in 2007-08.

Two negative elements of the invisibles balance deserve more analysis. Investment income predictably exhibits a deficit. Both inflows and outflows of investment income have increased sharply in 2007-08. However, the rise in inflows should not suggest that the much-vaunted new international clout of Indian corporates is finding expression in the balance of payments as well, as reinvested earnings of Indian investment abroad accounted for only a small part of the inflows. Instead, these inflows were dominated by the interest earnings on foreign exchange reserves held abroad, which amounted to more than $10 bn, or 73 per cent of the total inflows on this account.

Meanwhile, interest payments on external commercial borrowing (ECB) emerged as one of the largest outflows of investment income in 2007-08, amounting to $4.2 bn – an increase of 250 per cent over the previous year! The relaxation of rules for ECBs has clearly led to a significant expansion of such borrowing by Indian companies, and some of this may become more problematic as higher global interest rates and deceleration of growth affect the ability to repay. Repatriation of dividends and profits by multinational firms operating in India remained high at $3.3 bn.

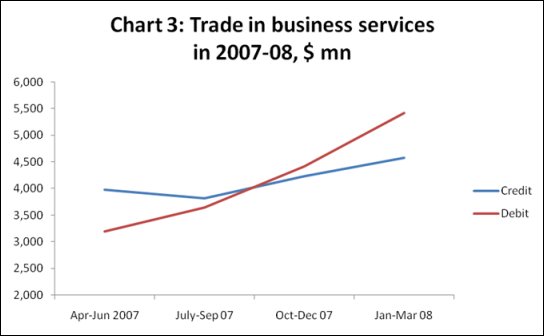

The other significant negative item is that of business services. While the deficit on this account was small, it is still significant because this was a positive item until very recently. In fact, this account turned negative only in the middle of last year, as Chart 3 shows. Within business services, over the entire year, the categories of business and management consultancy and architectural, engineering and other technical services showed substantial deficits.

The

travel account of invisibles is still in surplus, but that surplus has

been declining in recent years as economic liberalisation has increased

both the volume and value of outbound tourist and business traffic by

Indian residents. Travel payments (outflows) increased sharply by 38 per

cent in 2007-08.

Clearly, therefore, there are some areas of concern in recent trends in the current account. When these are combined with the clear signs of fragility in the captial acount, including the heavy dependence upon short-term flows, we cannot continue to treat the accretion to the country’s foreign exchange reserves as a sign of strength.

Clearly, therefore, there are some areas of concern in recent trends in the current account. When these are combined with the clear signs of fragility in the captial acount, including the heavy dependence upon short-term flows, we cannot continue to treat the accretion to the country’s foreign exchange reserves as a sign of strength.

©

MACROSCAN 2008