Themes > Features

29.08.2011

The Global Recession and India*

For

the global economy, August 2011 was a particularly bad month. A string

of economic indicators released early that month suggested that close

to four years after the onset of the global recession in December 2007

a sluggish world economy was set to sink again.

Sentiment too was at an exceptional low. Though completely out of line

and even irresponsible, the first-in-history downgrade of US Treasury

bonds by Standard and Poor's did reflect the mood in the market. Though

the assessment was based on wrong numbers, the fact that the debt of

world's most powerful country that was home to its reserve currency

was even considered to be of suspect quality was telling.

Besides the never-ending crisis in Europe, one factor explaining this

despondency was the fear of a second recession within half a decade.

The news from almost all sources was disconcerting. Recovery from the

recession was still sluggish in the U.S., Japan, that had been experiencing

long-term stagnation, had been devastated by a wholly unexpected exogenous

shock. And, France had announced that it had experienced virtually no

growth in that quarter. But the real dampener was the release of evidence

that the strongest economy in the rich nation's club-Germany-was losing

all momentum, registering a growth rate of just 0.1 per cent in the

second quarter. The real economy crisis had penetrated Europe's core,

pointing to the possibility of a return to recession in the Eurozone

as a whole (which registered 0.2 per cent growth).

For an India that is now more integrated with the world economy this

has to be bad news. But if the Government of India is to be believed,

the Indian economy is not likely to be very adversely affected by the

current round of global volatility. Finance Ministry sources argue that

the Indian economic growth story is so robust that the current uncertainty

will cause no more than a minor blip in its confident trajectory.

Consider, for example, the Indian government's response to the market

collapse that followed the US debt standoff and subsequent Standard

and Poor's downgrade. While acknowledging that India would be impacted,

the effort was to play down the likely intensity of that impact. ''Our

institutions are strong and [we] are prepared to address any concern

that may arise on account of the present situation,'' Finance Minister

Pranab Mukherjee reportedly stated. He also promised that the government

''will fast track the implementation of the pending reforms and keep

a close eye on international developments.''

That response misses the point. The problem is not that India is not

adequately reformed, but that past reforms have resulted in its greater

integration through flows of goods, services and finance with the global

economy.

One

obvious and important consequence of the global downturn is bound to

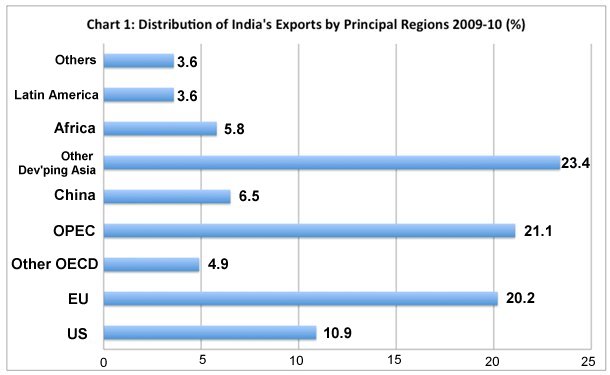

be a fall in exports revenues. As Chart 1 shows, the European Union

accounts for 20.2 per cent of India's merchandise exports and the US

for another 10.9 per cent. Thus, markets accounting for close to a third

of India's exports are already stagnating or in recession. Only two

regions can, hypothetically, counter this tendency: Developing Asia

(excluding China) and the OPEC countries. The former accounts for a

sizable 23.4 per cent of India's exports and the latter for another

21.1 per cent. However, most of developing Asia would be adversely affected

by the OECD downturn to a greater extent than India. And unless geopolitical

developments intervene, a global recession would moderate oil prices

and dampen import demand from the OPEC bloc. Finally, the hope that

China would be a balancing force is of less relevance to India since

it accounts for just 6.5 per cent of the latter's exports. Overall,

India is likely to take a hit in terms of its exports of goods, which

has been a source of buoyancy recently.

The other significant source of demand and revenue that is likely to

be adversely impacted is services. As per Balance of Payments data,

gross revenues from the exports of software services amounted in 2010-11

to as much as 24 per cent of the gross revenues from merchandise exports.

In 2009-10, the US alone accounted for 61 per cent of India's total

software exports. European countries (including the UK) followed with

as much as 26.5 per cent. If these two regions are the first to be hit

by the recession, it is unlikely that software export revenues would

remain unscathed. Over the period 2004-05 to 2009-10, services accounted

for 66 per cent of the increment in India's GDP. And revenues from software

services amounted to 9.4 per cent of the GDP from services (excluding

public administration and defence). The deceleration or decline in software

export revenues is bound to affect GDP growth adversely.

Besides export volumes and revenues, the other reason why India is likely

to be adversely affected by global uncertainty is exposure to global

finance. Direct exposure to international financial assets, including

the now less valuable debt issued by OECD governments, is only a small

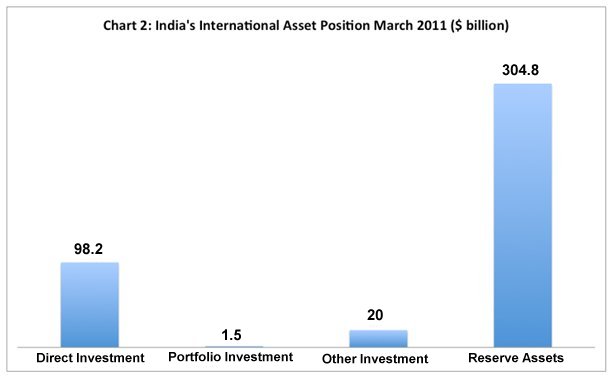

part of the problem. As the distribution of India's gross international

asset position (Chart 2) indicates, the two important forms those assets

take is direct investment and accumulated reserve assets. Portfolio

and other forms of investment are small or negligible. Since private

players largely hold direct investment assets, the squeeze in global

demand would affect the overseas revenues of these firms, but possibly

not do too much damage to the Indian economy.

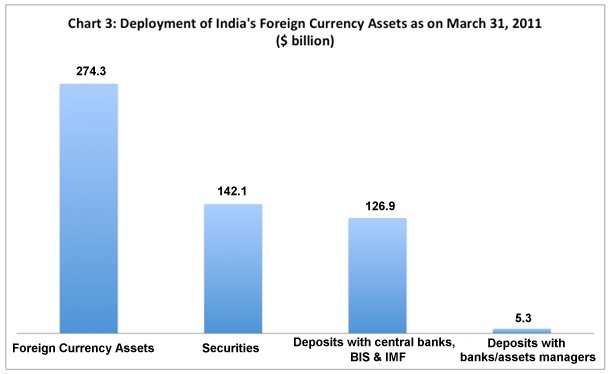

What is more of an issue is the fate of the $274 billion of foreign

currency assets (out of a total of $305 billion of reserve assets) held

by India. While $127 billion of these are held as deposits with central

banks, the Bank of International Settlements (BIS) and the IMF, as much

as $142.1 billion is invested in securities, consisting largely of government

securities (Chart 3). With the uncertainty surrounding the value and

soundness of public debt, the danger of the erosion of the value of

those assets is now significant. For example, India holds $41 billion

of US Treasury securities that have been downgraded recently by S&P.

The balance is likely to be in the even more suspect public debt of

European governments.

In addition to this, banks in India reporting to the BIS have disclosed

holdings amounting to $31.3 billion in financial assets abroad. Of these,

$14.9 billion are the external positions of banks in foreign currencies

vis-à-vis the non-bank sector abroad. These exposures too are

vulnerable given the volatility in financial markets in the OECD countries.

While the sums involved may be small (relative to the $1.2 trillion

held by China in US Treasury bonds, for example) they are of significance

because of the nature of India's reserves. Unlike in the case of China,

the reserves that insure India against adverse global responses are

not earned through current account surpluses, but are drawn from what

foreign investors have delivered in the past. They represent liabilities

that are being held as assets that on average yielded returns as low

as 2.09 per cent over the year ended June 201 (down from 4.16 during

2008-09). If the value of those assets is eroded, other things constant,

India's ability to cover its liabilities is eroded as well.

Besides this there is the fact that because of the presence of legacy

capital in the country (consisting, as of March 2011, of $204 billion

of direct investment, $174 billion of portfolio investment and $265

billion of debt and other investments) India is vulnerable to global

investor sentiment. International finance may assess its so-called fundamentals

very differently from the way they are assessed by the government.

Consider the issue that now captures financial market attention: public

debt. The experience in Greece, Spain, Portugal and elsewhere suggests

that finance capital is increasingly ''intolerant'' of what is perceived

as excessive public debt. Though India's gross public debt to GDP ratio

declined from 75.8 per cent to 66.2 per cent between 2007 and 2011,

it still is among the highest in the region. India's 66.2 per cent level

compares with Malaysia's 55.1, Pakistan's 54.1, Philippines' 47, Thailand's

43.7, Indonesia's 25.4 and China's 16.5 (Eswar Prasad calculations quoted

in ''Comparing the burden of public debt'', interactive graphic on the

Financial Times website).

It is no doubt true that a number of factors make Indian public debt

less of a problem than in many other contexts. To start with, much of

public debt in India is denominated in Indian rupees and is owed to

resident agents and therefore is unlikely to be adversely affected by

uncertainty in international debt and currency markets. Secondly, within

the country public debt is largely held by the banking system dominated

by public sector banks. They are subject to government influence and

are unlikely to respond to developments in ways that make bond prices

and yields extremely volatile. Given these circumstances, public debt

is not a potential trigger for a crisis and in any case should not worry

private financial interests.

But if a wrong downgrade can make a difference to US markets and interest

rates, so can it for India's. It is in that background that we should

view reports of S&P's statement that fiscal capacities in Asian

emerging markets, including India, have shrunk relative to 2008. This,

it has argued, would mean that in the event of a second global slowdown:

''The implications for sovereign creditworthiness in Asia-Pacific would

likely be more negative than previously experienced, and a larger number

of negative ratings actions would follow.''

If, for its own reasons, S&P needs a target to declare that some

governments in the Asia-Pacific are excessively indebted, then India

is in the firing line. India has been a favoured target of foreign finance.

And if it does not satisfy the latter's requirements, it can fall out

of favour. Clearly, a fiscal surplus and a low public debt to GDP ratio

are part of those requirements even if for the wrong reasons. India

has neither.

*

This article was originally published in Business Line on August 23,

2011.

©

MACROSCAN 2011