| |

|

|

|

|

Ill

Winds from Europe* |

| |

| Aug

8th 2012, C.P. Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh |

|

The

crisis in Europe intensifies. Spain, which though

yet to fully implement the €100 billion bailout of

its banks, is preparing for a bailout of its government.

Spain's government that needs to borrow as much as

€385 billion, is facing bond yields at record highs

of as much as 7.75 per cent. That is a combined burden

that would be impossible to carry, even for a country

with public debt to GDP much lower than Italy. So,

another country, after Greece, seems set for a vicious

circle of new funding accompanied by austerity; slow

growth, high unemployment and low revenues; a collapsing

fisc; and one more bailout. As a result, fears of

the fallout within and outside Europe are growing.

Some evidence is already disconcerting. Italy is widely

predicted to be the next victim in Europe. The recovery

has lost steam in the US. And the so-called emerging

market economies in Asia, especially China and India,

which buffered the effects of the previous crisis,

are also experiencing a deceleration in growth.

It is the fallout outside Europe, especially Asia,

which is now under scrutiny. Two central bankers,

from institutions as diverse as the Federal Reserve

of Boston and the Bank of Japan, have recently warned

that Asia is likely to be affected. This would prolong

and intensify the incipient crisis, since these countries

are seen as having substantially exhausted the fiscal

and monetary headroom they had to deal with a downturn.

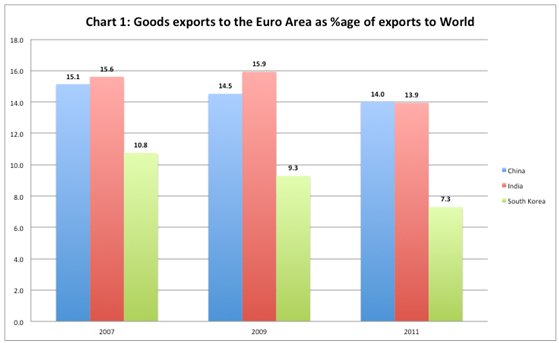

The most obvious way in which the European crisis

is affecting and would continue to affect the region

is through a decline in exports. If we take three

significant late industrialisers in Asia-China, India

and South Korea-we find that in the case of two of

them (China and India) the value of their exports

of goods to Europe was between 15 and 16 per cent

of the total exports of goods from these countries

(Chart 1). That share has fallen between 2009 and

2011, reflecting the effects of the crisis in Europe.

In India's case, these developments in the trade in

goods would have been aggravated by the slowdown in

its services exports to Europe, whose share in India's

large exports of services has been rising. Even in

those Asian countries where exports to Europe are

not as important, the impact of the crisis can be

significant. For example, South Korea's exports of

goods to Europe amounted to just above 10 per cent

of its aggregate exports of goods before the crisis,

but even that figure had fallen to 7.3 per cent by

2011.

However, the trade route is only one among the ways

in which the contagion effects from Europe can reach

Asia. A pathway that could be more important is the

increased integration of Asian financial markets with

European markets in the aftermath of financial liberalisation

in these countries and of the surge in cross-border

capital flows that the world had experienced for half

a decade before the crisis.

Chart

1 >>

(Click to Enlarge)

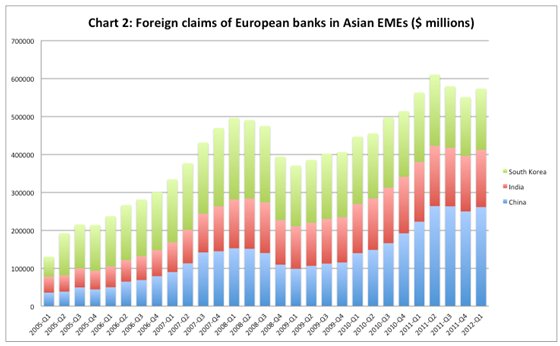

One

measure of this kind of integration is the outstanding

claims held by European banks in Asia. As estimates

from the Bank for International Settlements reported

in Chart 2 indicate, such exposure has risen in all

three countries being considered here and is large at

present. From $35.7 billion, $42.3billion and $52.5

billion in the first quarter of 2005 in China, India

and South Korea respectively, European bank claims had

risen to $261 billion, $150.6 billion and $161.4 billion

respectively by the first quarter of 2012. Moreover,

in all cases the exposure of institutions located in

Europe was in the neighbourhood of 50 per cent of all

international claims on these countries. Unlike in the

case of goods exports, South Korea's exposure to Europe

on this count is also comparably high. And interestingly,

China, considered to have a less open banking sector,

has a much higher level of exposure than the other two

countries.

Chart

2 >>

(Click to Enlarge)

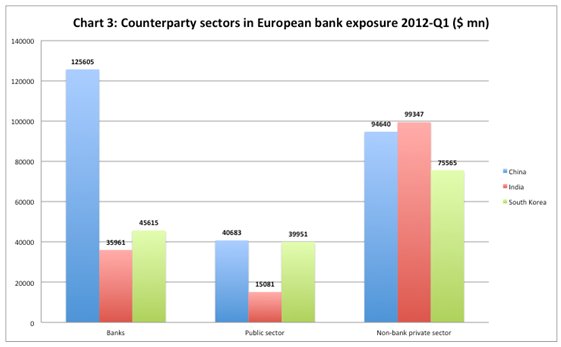

The effects of financial liberalisation on borrowing

in these countries are visible in the composition

of the counterparties to which European banks are

exposed (Chart 3). In all three countries, claims

on the public sector are the smallest. In India and

South Korea, claims on the non-bank private sector

dominate, whereas in the case of China, while claims

on the non-bank private sector are substantial, those

on the banks dominate overwhelmingly. Clearly, in

the case of China, banking liberalisation has encouraged

borrowing abroad to finance lending to local borrowers.

Chart

3 >>

(Click to Enlarge)

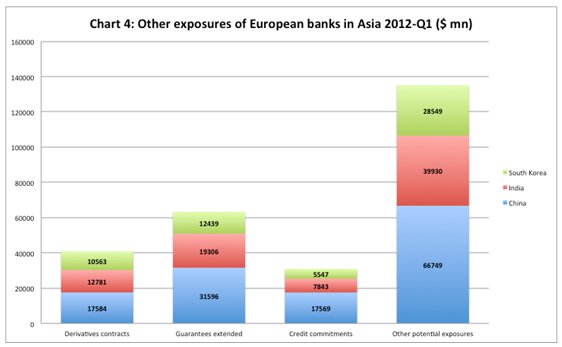

Needless to say, the exposure of foreigners in these

countries is not restricted to claims in the form of

credit provided to local institutions or agents either

from abroad or through an institutional presence in

the country concerned. There are other forms of exposure,

such as through derivative contracts or the provision

of guarantees. As Chart 4 indicates, such exposures

can be substantial, and can equal or exceed formal claims

on a country and its institutions. Surprisingly, the

ambiguously defined category ''other potential exposures''

dominates.

This huge exposure of European banks (and other financial

institutions) to Asia, points to the other ways in which

the crisis in Europe can impact the Asian region. To

start with (as is already clearly happening when we

examine European figures excluding the UK), the crisis

would require European banks to unwind and reduce their

exposure in Asia in order to mobilise resources to cover

losses or meet commitments at home. The result is a

return flow of capital.

Three kinds of effects are likely to ensue. The first

could be a weakening of Asian currencies, as already

seen in India, which not only generates instability,

but also puts pressure on domestic agents, including

firms, with foreign exchange commitments to meet. The

local currency outlay they would have to make to meet

those commitments would increase, putting pressure on

their balance sheets and profit and loss accounts.

Chart

4 >>

(Click to Enlarge)

The second would be instability in financial

markets, inasmuch as these claims directly or indirectly

finance stock market activity. Recently, Eric Rosengren,

the President of the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston

showed (http://www.bostonfed.org/news/speeches/rosengr

en/2012/070912/index.htm#figure10)

that greater financial integration was increasing

the correlation between the stock returns of large

European banks and global banks in China and Japan.

In his view, ''while Asian banks did not have a

high correlation with U.S. and European bank stock

returns during 2007 and early 2008, Asian banks

are likely to be more impacted now should a significant

shock occur in Europe.'' This only goes to show

that ''as interconnectedness increases globally,

it will be difficult for any one region to insulate

itself from financial strains or crises elsewhere

in the world.'' The effects can take many forms.

They could for example destabilise financial markets

in emerging Asia with unexpected consequences. Or

they could, through negative wealth effects, impact

adversely on spending and demand. As Hirohide Yamaguchi,

the Deputy Governor of the Bank of Japan noted recently

(http://www.boj.or.jp/en/annou

ncements/press/koen_2012/ko120709a.htm/,

''jittery market sentiment … will make Asian economic

entities' sentiment cautious, thereby containing

their spending.''

Finally, an exit of capital from Asian countries

can result in a liquidity crunch that can affect

domestic lending adversely, reining in the credit-financed

private housing investment and consumption that

has come to characterise these countries with adverse

implications for demand expansion and growth.

Some combination of these effects does play a role

in explaining the slowdown of growth in Asia and

could aggravate it in the months to come. This calls

for a combination of a fiscal stimulus and an easing

of credit provided at reasonable rates of interest.

However, fiscal conservatism, an accumulated public

debt burden and inflation triggered by the rise

in global oil and food prices, is holding back governments

and central banks, which are in any case under pressure

from global finance to curb spending and tighten

monetary policy. That could bring the yet-unfolding

crisis in Europe to Asia. In which case these countries

would be contributors to rather than buffers against

the next crisis, if it materialises.

*

This article was originally published in the Business

Line on 6 August 2012.

|

| |

|

Print

this Page |

|

|

|

|