The

National Common Minimum Programme of the UPA government

promised many things, and on some of the more crucial

issues (such as on the Employment Guarantee ACT) the

current central government has shown itself to be

less than enthusiastic in terms of fulfilling the

true spirit of its promise. But on other matters which

are more in tune with the basic neo-liberal economic

policy paradigm which the government continues to

uphold, it has acted with alacrity.

The

most recent example is in terms of the debate on subsidies

provided by the central government. The NCMP had promised

that ''All subsidies will be targeted sharply at the

poor and the truly needy like small and marginal farmers,

farm labour and urban poor.'' However, the actual

analysis provided by the Finance Ministry in its recent

Report prepared with assistance from the National

Institute of Public Finance and Policy (''Central

government subsidies in India: A report'', December

2004) suggests that this is to be used as a justification

for overall cutbacks in subsidies, regardless of their

effects on the poor and needy.

This discussion is not new, of course: the period

since 1991 has been characterised by a generalised

distaste for subsidies among policy makers, who have

tended to blame them for virtually all fiscal problems,

and have used this smokescreen to divert attention

from the inability to raise tax revenues. And so declarations

by the government as well as explicit attempts to

reduce direct subsidies on food and fertiliser have

been important parts of the economic reform programme

since 1991.

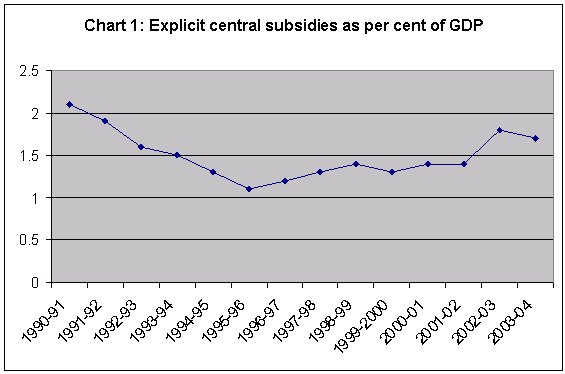

All this has been despite the fact that direct subsidies

paid by the central government amounted to a very

small proportion of GDP over this entire period. Chart

1 shows that since 1991, central government subsidies

have never crossed 2 per cent of GDP. Indeed, the

ratio of all direct subsidies paid by the central

government to GDP has actually fallen from around

1.85 per cent in the triennium beginning 1990-91 to

1.6 per cent in the triennium ending 2003-04.

Chart

1 >> Click

to Enlarge

This is really a trivial amount not only in terms

of the past, but also in relation to international

experience. In countries of western Europe, for example,

direct subsidies in the form of unemployment benefits

and social security can make up as much as half of

the current spending of governments.

Because direct subsidies are so low, the obsession

with reducing them has also necessarily required that

the attention be shifted from direct to ''indirect''

or implicit subsidies, calculated on the basis of

working out the excess of expenditure over receipts

for all major items of government expenditure. As

early as 1997, a similar Discussion Paper released

by the then government (which contained many of the

faces that are so prominent today) concluded that

total subsidies (including these implicit subsidies

reflecting low or non-existing user charges for public

services) in India were not only four to five times

higher than explicit subsidies, but constituted an

unacceptable 14.4 per cent of GDP.

This estimate was arrived at from budget documents

simply by calculating the shortfall in public revenues

(or "recovery" of expenditure through charges)

relative to the actual public expenditure incurred.

Using the notion of ''merit'' and ''non-merit'' subsidies,

(that is, those on goods and services with significant

externalities in which private and social valuations

would therefore differ significantly, and those without

large externalities) it was argued that subsidies

accounting for 10.7 per cent of GDP were unwarranted.

It was posited that the distributive consequences

of subsidies were adverse since they were not properly

targeted, quite obviously in cases where the subsidy

was administered through inputs (fertiliser, electricity,

diesel, irrigation, etc.) and even in cases where

they applied to a final good (food). As a result,

it was proposed that most of these subsidies were

best done away with, and that the best way to do so

was "through phased increases in recovery charges".

Thus the 1997 paper argued that there was a strong

case for an almost across-the-board increase in user

charges for services provided by the central and state

governments. This was then used to justify the increase

in fertiliser prices which had negative effects not

only on fertiliser consumption and farm productivity,

but also on the viability of cultivation. It was used

to explain the completely ham-handed and ultimately

counterproductive attempt to reduce the food subsidy

by raising issue prices of food grain and ''targeting''

the poor. This led to reduced offtake and not only

a paradox of large publicly held food stocks in midst

of hunger, but also an actual increase in subsidies

on holding of stocks, which were then exported at

prices even lower than earlier denied to the domestic

poor.

Several critiques of that paper comprehensively established

that the basic methodology of this exercise was invalid.

The classification of merit and non-merit subsidies

emerged as being very subjective and often bizarre.

The principal failure of this methodology was that

it recognised only one reason (the presence of externalities)

why the private valuation of benefits could deviate

from their social value to society. But subsidies

are essentially no more than negative taxes, so externalities

cannot be the only reason why societies choose to

subsidise particular activities, just as there are

basic socio-political and income-distributional decisions

which determine the pattern of taxation. In fact,

there can be many cases where the fact that public

expenditure exceeds cost recovery need not be a problem

but could in fact be socially desirable.

This is because market failure does not occur only

at the microeconomic level as is true in the case

of externalities. Even at the macroeconomic level,

government expenditure plays a critical role in maintaining

levels of economic activity, and to characterise much

of this as implicit ''subsidy'' is therefore highly

misleading. In market-based systems where savings

and investment decisions are taken by atomistic decision-makers

based on their guesses and expectations of an uncertain

future and of the decisions to be taken by others,

there is an inherent tendency towards an unemployment

equilibrium. Faced with this prospect, governments

tend to intervene with counter-cyclical demand management

policies aimed at dealing with the prospect of a recession,

and in some cases they attempt to mitigate the adverse

consequences of unemployment through mechanisms such

as unemployment benefit.

In addition, market-based systems tend to be characterised

by an unequal distribution of assets and incomes,

which reduces the ability of some individuals to participate

in the market and adequately finance their basic needs.

It is to deal with these features of the market economy

that the developed industrial nations have created

an elaborate welfare state, which has been dismantled

only partially even in the current "market-friendly"

ideological environment, and why direct subsidies

continue to be such an important part of the expenditure

of such governments.

Given this background, it is disturbing to see the

current Finance Ministry producing almost the same

false arguments of the earlier Paper, and coming to

even more unwarranted conclusions with respect to

policy. The only modification (which is not really

of much signfiicance) is the further segregation of

''merit'' subsidies into two categories based on degree

of merit. The methodology for calculating implicit

subsidies is the same, and yields a figure of 4.18

per cent of GDP for the year 2003-04.

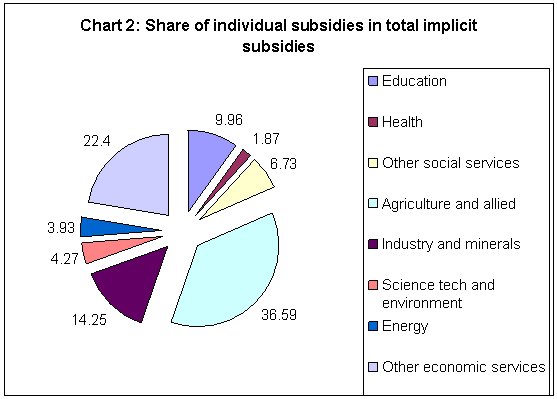

Chart

2 >> Click

to Enlarge

Even the calculations presented in the Paper indicate

that these are mostly spent on critical areas such

as agriculture, industry and education. Chart 2 shows

the break-up of implicit subsidies as described in

the Paper. And these individual implicit subsidies

(which are already worked out on the basis of a problematic

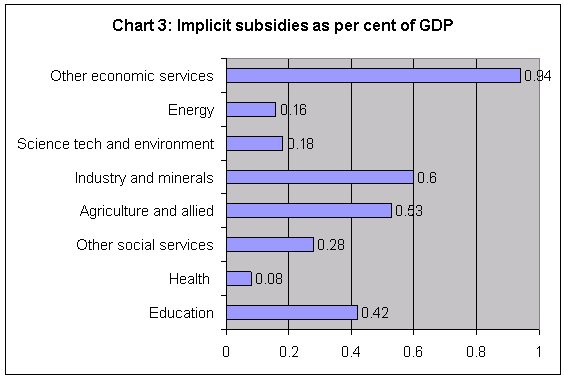

methodology) come to tiny percentages of GDP, so small

that they are barely to be noticed in public finance

terms. Chart 3 provides an estimate of these. In fact,

if social services such as health and education as

well as expendtiure for the development of agriculture

and industry is to be provided in a socially optimal

way and provided to all of those who are poor and/or

deserving, then higher levels of implict subsidy are

called for, not lower ones.

Chart

3 >> Click

to Enlarge

But this faulty calculation (which also throws up

anomalies such as the railways providing a negative

subsidy, that is a net profit, for the government)

is then used to make very sweeping and even alarming

recommendations for cutting all subsidies. Based on

the unjustified axiom that even so-called ''merit''

subsidies should be reduced as much as possible, the

Report makes policy proposals that are not only wrong-headed

but also breathtaking in their insensitivity to the

current economic situation and problems of ordinary

people.

Thus, it calls for reducing Minimum Support Prices

for farmers at a time of widespread agrarian crisis.

It suggests that the present two-tier system of prices

in the Public Distribution System should be done away

with (presumably by revising the lower prices upwards)

along with a system of food coupons for BPL families.

Fertiliser prices should be raised. LPG and kerosene

subsidies, which affect largely middle class and poor

households, are seen as objectionable and requiring

further reduction, notwithstanding the recent price

hikes which have already adversely affected the poor.

Economic services are to be priced to varying degrees,

which essentially means increasing user charges regardless

of the merits and positive externalities of the services

in question. Even social services do not escape the

net: the Report argues that ''while humand development

is a necessary concern of the welfare state. It may

be necessary to reassess policies in this area at

the micro level to temper this concern with the equally

legitimate concern of burgeoning public expenditures.''

(page 22).

The irony is that in fact public expenditures have

not been burgeoning - as a share of GDP, non-interest

public expendiutre has actually been falling in recent

years, and this is part of the economic problem of

the country. This falling share of public expenditure

has been associated with much less infrastructure

development, poor and declining public services, and

a collapse of employment generation. So the economic

agenda should really be to think of ways of increasing

public expenditure, not cutting it further.

The focus on reducing expenditure only comes about

because of the failure to raise tax revenues. And

this has been an integral part of the fiscal strategy

associated with neo-liberal reform. The cuts in indirect

and direct tax rates have been associated with falling

central tax to GDP ratios, but the current Finance

Ministry does not appear to see reversing this trend

as a priority. Instead, it has already simply given

away around Rs. 6,000 crores to stockbrokers as lost

taxes, first by replacing the capital gains tax with

a turnover tax, and then by reducing that proposed

tax to a fraction of the original demand because of

protests on Dalal Street.

All fiscal measures have very strong implications

for income distribution. And they reflect very clearly

the intentions of the government and which sections

of the people and the economy the government serves.

If this Paper is an accurate reflection of the curent

thinking of the government in the matter of subsidies,

then it is bad news not only for the poor and needy

who require such subsidies for survival, but also

for development of the economy in general.