Themes > Features

12.12.2007

Wheat Inflation and India

Having

decided to import wheat in sequential lots to beef up its reserve, the

government finds that it is having to pay continuously rising prices for

the commodity. According to reports, as compared with the weighted average

price of $205 per tonne paid for wheat imported in 2006-07, the average

price paid on tenders floated on June 26, August 30 and November 12, 2007

was $326, $389 and $400 per tonne respectively. This takes the weighted

average price paid so far this year to $372 per tonne or 80 per cent higher

than in the previous year. With one more tender floated on November 26

and more imports likely if an early election is planned, this figure may

rise even further.

It is undoubtedly true that with total imports contracted thus far this year valued at a little more than $600 million, the foreign exchange burden imposed by these imports is small change when compared to the $270 billion of reserves that India holds. However, the high price of imports does imply the price paid for imports is 1.5 to two times the procurement price offered to domestic farmers. Since these imports are being used to shore up stocks meant for the public distribution system, this also means that the budgetary subsidy for wheat would be that much higher, with the subsidy being paid to international suppliers in order to dampen domestic inflation.

While high international prices are the immediate cause of these outcomes, they also reflect the failure of the government to ensure adequate domestic procurement and to assess global price trends. Operating on the premise that international price would be pushed higher if India chose to make large imports, the government may have decided to import the commodity in smaller lots. But global developments pushed up prices in any case, making the sequential import strategy a mistake.

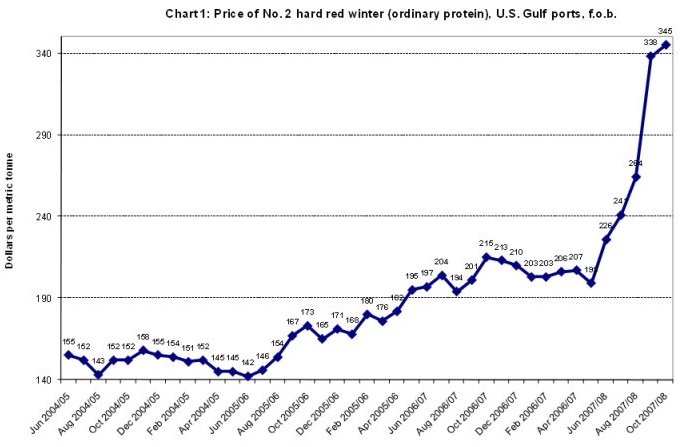

Across the world, food prices, especially those of staples like grains, have been rising sharply in recent months. Wheat, the staple used to make bread, pasta, chapatti and much else, epitomises the trend. The free-on-board price of US-exported "No. 2 hard red winter wheat", which stood at $199 per metric tonne in May of 2007, rose by 70 per cent to touch $345 per metric tonne in October 2007.

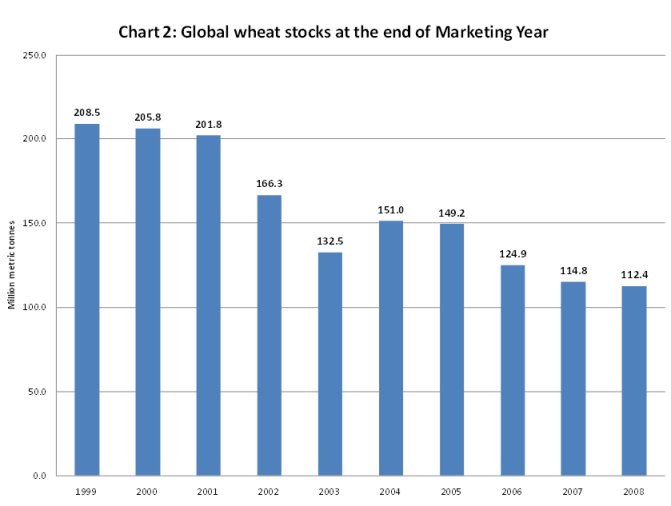

The surge in prices of this globally consumed staple has triggered widespread protests. Italian consumer organisations even called on members to "sacrifice" their (wheat-based) pasta consumption for a day to register their dissent. Protest of this sort has set policy makers in search of explanations for what investment-banking firm Merill Lynch has reportedly termed "agflation". With agricultural prices conventionally seen as being determined by the relative levels of demand and supply, attention is focused on the US Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) estimate this September that global stocks of would touch wheat would touch 112.4 million tonnes at the end of this marketing year (May 2008), their lowest in 30 years. Year-end stocks have been declining continuously since the end of marketing year 2003-04, when they stood at 151 million metric tonnes. That figure too was below the May 1999 high of 209 million metric tonnes. Clearly consumption has been running ahead of production over the long run, almost halving year-end inventories over a decade

It is undoubtedly true that with total imports contracted thus far this year valued at a little more than $600 million, the foreign exchange burden imposed by these imports is small change when compared to the $270 billion of reserves that India holds. However, the high price of imports does imply the price paid for imports is 1.5 to two times the procurement price offered to domestic farmers. Since these imports are being used to shore up stocks meant for the public distribution system, this also means that the budgetary subsidy for wheat would be that much higher, with the subsidy being paid to international suppliers in order to dampen domestic inflation.

While high international prices are the immediate cause of these outcomes, they also reflect the failure of the government to ensure adequate domestic procurement and to assess global price trends. Operating on the premise that international price would be pushed higher if India chose to make large imports, the government may have decided to import the commodity in smaller lots. But global developments pushed up prices in any case, making the sequential import strategy a mistake.

Across the world, food prices, especially those of staples like grains, have been rising sharply in recent months. Wheat, the staple used to make bread, pasta, chapatti and much else, epitomises the trend. The free-on-board price of US-exported "No. 2 hard red winter wheat", which stood at $199 per metric tonne in May of 2007, rose by 70 per cent to touch $345 per metric tonne in October 2007.

The surge in prices of this globally consumed staple has triggered widespread protests. Italian consumer organisations even called on members to "sacrifice" their (wheat-based) pasta consumption for a day to register their dissent. Protest of this sort has set policy makers in search of explanations for what investment-banking firm Merill Lynch has reportedly termed "agflation". With agricultural prices conventionally seen as being determined by the relative levels of demand and supply, attention is focused on the US Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) estimate this September that global stocks of would touch wheat would touch 112.4 million tonnes at the end of this marketing year (May 2008), their lowest in 30 years. Year-end stocks have been declining continuously since the end of marketing year 2003-04, when they stood at 151 million metric tonnes. That figure too was below the May 1999 high of 209 million metric tonnes. Clearly consumption has been running ahead of production over the long run, almost halving year-end inventories over a decade

Given

this tendency, any short term changes either in consumption or supply

can result in imbalances that influence price movements. Moreover, global

surpluses are concentrated with a few nations. World exports of wheat

account for around 18-20 per cent of world production. And, six countries

or groupings-Argentina (8.9%), EU (9.9%), Russia (11.3%), Australia (12.2%),

Canada (13.2%) and the US (28.2%)-account for close to 85 per cent of

world exports. Given this context, the USDA blames supply side developments

in these countries for the upward pressure on prices. For example, Canada’s

wheat output is expected to fall by roughly a fifth this year because

of bad weather. Weather-related factors are also expected to reduce supplies

from major exporters such as the EU, Australia and Argentina, restricting

availability in global markets.

Further,

the increase in wheat prices this has triggered is not reducing demand.

Not only are big wheat buyers such as Brazil and Egypt continuing to buy,

but import dependent countries like Japan and Taiwan have rushed into

the market early to secure their supplies. Moreover, occasional buyers

like India, have also been significant purchasers in recent times. The

net effect has been a surge in prices, argue analysts.

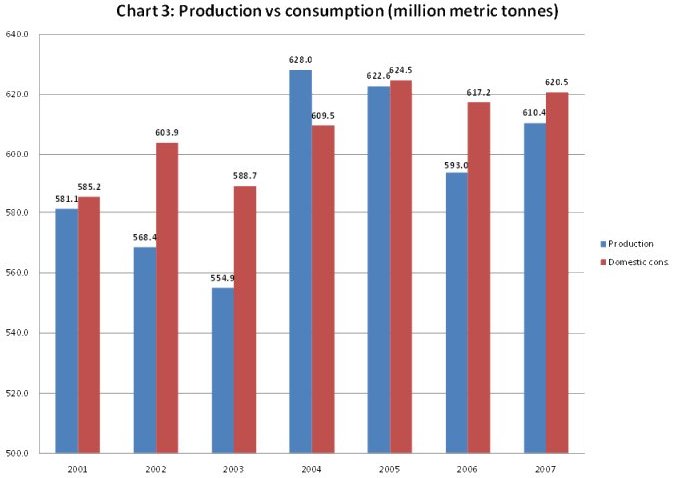

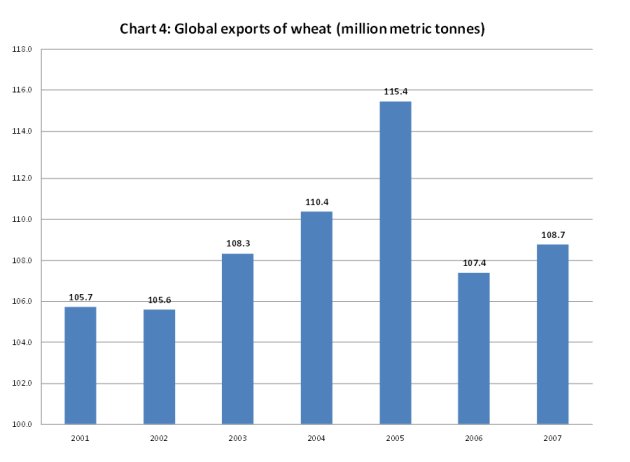

The data partly bears out these trends. The gap between production and domestic consumption across nations has been declining in recent years (Chart 3). So countries have less to export (Chart 4).

However, even accounting for these factors, the extremely sharp increase in prices in recent months is not easily explained. Even though global stocks have been falling, they are still at a comfortable 114.8 million metric tonnes or 18.8 per cent of global production-a figure roughly equivalent to the proportion of production that is globally traded in a year. Taking into account the fact that rising prices would encourage farmers to plant more wheat, production can also be expected to adjust, even if with a lag. For example, though exports in 2007-08 from the EU and Canada are expected to fall by 1 million tonnes each and that from Australia by 1.5 million tonnes because of reduced crop prospects, exports from Russia and the US are expected to rise by 1 million tonnes each because of improved production and the incentive created by higher prices. In the circumstances the sudden and sharp rise in prices seems difficult to explain based on demand and supply alone.

The data partly bears out these trends. The gap between production and domestic consumption across nations has been declining in recent years (Chart 3). So countries have less to export (Chart 4).

However, even accounting for these factors, the extremely sharp increase in prices in recent months is not easily explained. Even though global stocks have been falling, they are still at a comfortable 114.8 million metric tonnes or 18.8 per cent of global production-a figure roughly equivalent to the proportion of production that is globally traded in a year. Taking into account the fact that rising prices would encourage farmers to plant more wheat, production can also be expected to adjust, even if with a lag. For example, though exports in 2007-08 from the EU and Canada are expected to fall by 1 million tonnes each and that from Australia by 1.5 million tonnes because of reduced crop prospects, exports from Russia and the US are expected to rise by 1 million tonnes each because of improved production and the incentive created by higher prices. In the circumstances the sudden and sharp rise in prices seems difficult to explain based on demand and supply alone.

Fat

and rising margins garnered by monopolistic processors and retailers and

speculation in futures markets are seen by many to be playing a role.

Protesting against rising pasta prices outside the parliament in Rome,

Carlo Rienzi of the Codacons consumer association is reported by the Financial

Times to have berated politicians, wholesalers, retailers and speculators-"everyone

but farmers and consumers". Their actions are seen as having resulted

in the accumulation of large margins as wheat passes from the field to

the supermarket shelf.

The set of players whose trades are least transparent and whose effect

on prices least obvious are investors in futures markets. When in September,

a December wheat contract traded at the Chicago Board of Trade at a record

$9.11¼ a bushel, it was unclear whether traders were capturing

the level at which prices are likely to settle come December or influencing

the way prices would move in the weeks to December.

What is clear, however, is that financial investors (who are speculators

by design) see much gain in commodity, including wheat, futures. Noting

that financial investors have been increasing their stake in these markets,

The Economist (September 6, 2007) recently reported: "Trading in

agricultural futures, once a backwater, has boomed in recent years. In

addition to agri-businesses, more institutional investors-ranging from

hedge funds to pension funds-are investing. Last year nearly $3 trillion

in grain futures was traded on the Chicago Board of Trade (now part of

CME Group), the world's largest such market." And wheat is one of

the favoured commodities.

The Food and Agricultural Organization also reports an increase in speculative

activity in agricultural commodity markets. In a recent assessment, the

FAO argued that market-oriented policies are creating financial opportunities

in agricultural markets at a time when financial markets are awash with

liquidity. This abundance of liquidity has, in its view, "paved the

way for massive amounts of cash becoming available for investment (by

equity investors, funds, etc.) in markets that use financial instruments

linked to the functioning of agricultural commodity markets (e.g. future

and option markets)." Among such investors are speculators looking

to such markets, "as a way of spreading their risk and pursuing of

more lucrative returns. Such influx of liquidity is likely to influence

the underlying spot markets to the extent that they affect the decisions

of farmers, traders and processors of agricultural commodities."

The extent to which these factors have actually contributed to the recent

price increase is yet to be ascertained. But the fact that demand-supply

imbalances and stockholding levels cannot explain the recent price surge

in wheat and other agricultural commodities has strengthened the suspicion

that they have indeed had an effect.

India is partially insulated from the effects of these global trends.

Exports are not permitted and the minimum support price rules well below

import prices, so that global "agflation" is not being imported

into the country. But the government’s decision to allow private players,

including large international firms, a major role in domestic markets

has created a curious situation. According to reports, private companies

(such as ITC, Cargill, AWB India, Britannia, Agricore, Delhi Flour Mills

and Adani Enterprises) picked up around 20 lakh tonnes of wheat during

the recent rabi marketing season (April-July). While this may appear small

relative to total production such purchases can make a difference at the

margin to prices. In any case, they affect the ability of the government

to procure supplies to refurbish its reserves. Even though production

of wheat during 2006-07 is estimated at close to 75 million tonnes as

compared with 69 million tonnes in the previous year, procurement fell

short of expectations because the procurement price of Rs. 8.5 a kg ruled

well below market prices that have ranged between Rs.10 and Rs.12 a kg.

Though by July 19 procurement was, at 11.1 million tonnes, higher than

the 9.2 million tonnes recorded in 2006-07, it was way below the levels

of 16.8 and 14.8 million tonnes recorded in 2004-05 and 2005-06. With

offtake likely to remain high, this implies that buffer stocks could fall

below comfort levels. If low global stocks are seen to trigger inflation,

an inadequate buffer stock generates similar fears domestically.

Faced with the prospect of an early election and the evidence of inflation

in global wheat markets, the government that had earlier reversed a decision

to import wheat has now decided to import the grain, but in small sequential

lots. This, as noted earlier, has proved costly. A recent clarification

attributed the cancellation of the earlier import decision to the expectation

that global prices would fall in the wake of the harvest in major wheat

producing countries and the consequent view of the Integrated Finance

Division (IFD) of the Department of Food and Public Distribution that

"a very high benchmark price would be established for future wheat

imports."

With these expectations not being realised the government has now decided

to make the best of a bad situation created by wrong decisions on domestic

trade, procurement and imports. As clarified by the Union Food and Agriculture

Minister Sharad Pawar, the Empowered Group of Ministers took the recent

import decision, "influenced by the downward revision of the global

wheat production, apprehensions about some major wheat producing countries

placing restrictions on wheat exports and the Chicago Board of Trade (CboT)

futures showing an upward trend of wheat prices for December 2007 and

March 2008."

It was possibly the Indian decision that resulted in the sharp rise in

US export prices in August this year. Unfortunately neither the Indian

farmer nor the Indian government is gaining from these trends. And it

is not clear how long the Indian consumer would be even partially insulated

from their effects. Maybe Carlo Rienzi had got it right.

©

MACROSCAN 2007