Themes > Features

17.12..2008

Global Recession: How Deep and for How Long?

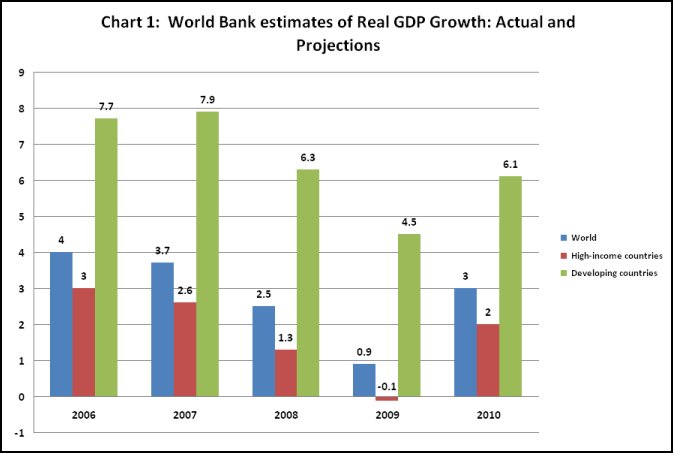

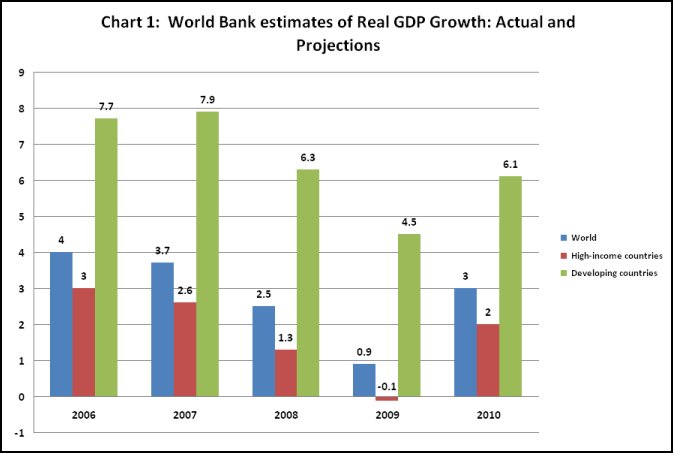

As

2008 entered its final month, predictions of where the world economy is

heading turned dire. The World Bank projected world output to grow by

a mere 0.9 per cent in 2009 (as compared with 2.5 per cent in 2008 and

a high of 4 per cent in 2006) and world trade to contract by a significant

2.1 per cent (compared to positive rates of growth of 6.2 per cent in

2008 and a high of 9.8 per cent in 2006). (Chart 1). Moreover, the World

Bank could identify no possible driver for a recovery in the coming months.

Other projections are even more pessimistic. Chapter 1 of the UN’s World Economic Situation and Prospects 2009, released in advance at the Doha Financing for Development conference, estimates that the rate of growth of world output which fell from 4.0 per cent in 2006 to 3.8 per cent in 2007 and 2.5 per cent in 2008 is projected to fall to -0.5 per cent in 2009 as per its baseline scenario and as much as -1.5 per cent in its pessimistic scenario.

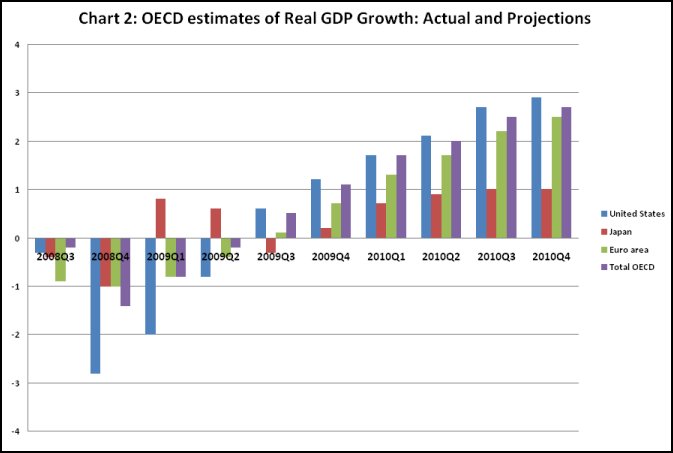

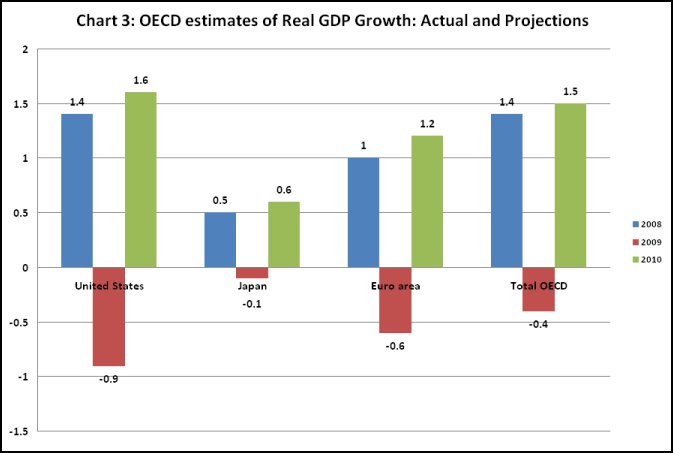

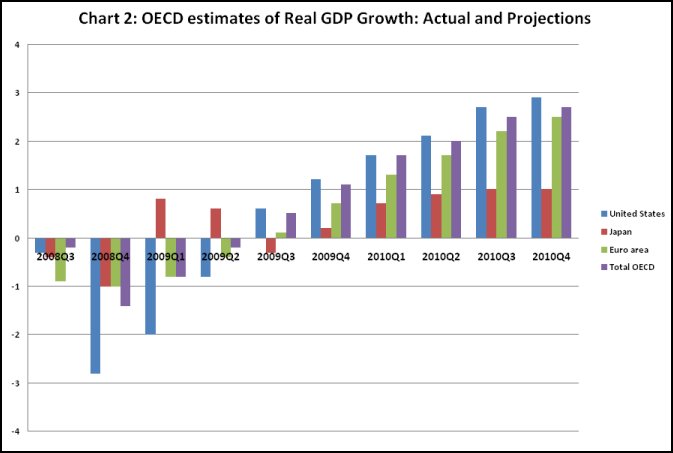

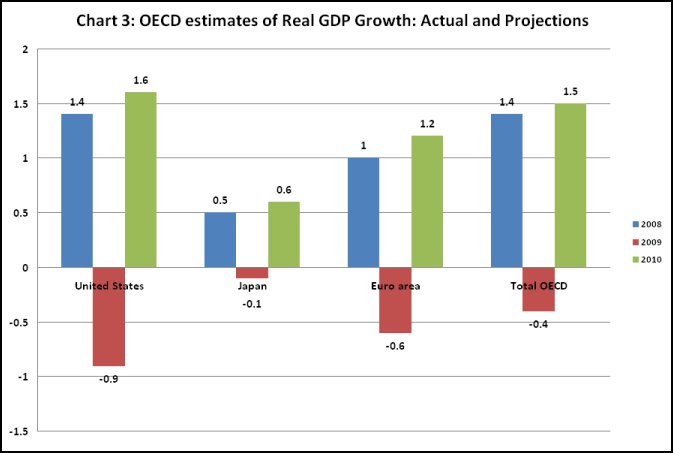

Finally, the recently released preliminary edition of the OECD’s Economic Outlook for end-2008 shows that GDP in most OECD countries declined in the third quarter and is likely to fall also in the fourth (Chart 2). In the event, GDP growth in the OECD area which fell from 3.1 per cent in 2006 to 2.6 per cent in 2007 and 1.4 per cent in 2008 is projected to fall to -0.4 per cent in 2009 (Chart 3), and the unemployment rate which rose from 5.6 per cent to 5.9 per cent between 2007 and 2008 is expected to climb to 6.9 per cent in 2009 and 7.2 per cent in 2010.

If these predictions turn out to be true, the prognosis is that what was a recession in 2008 could turn into a depression in 2009. Looking back, 2008 was a year when the recession unfolded. The recession in the US, reports indicate, is not recent but about a year old and ongoing. Short term indicators are disconcerting, but do not convey the real picture. Preliminary estimates of GDP growth in the United States during the third quarter of 2008 point to decline of half a percentage point. But GDP growth during the previous two quarters was positive at 2.8 and 0.9 per cent respectively. The only other quarter since early 2002 when growth was negative was the fourth quarter of 2007. Thus, going by the popular definition of a recession-two consecutive quarters of decline in real gross domestic product-the US is still to slip into recessionary contraction.

But the independent agency which is the more widely accepted arbiter of the cyclical position of the US economy is the Business Cycle Dating Committee of the National Bureau of Economic Research. This committee, which adopts a more comprehensive set of measures to decide whether or not the economy has entered a recessionary phase, has recently announced that the recession in the US economy had begun as early as December 2007. That already makes the recession 11 months long, which has been the average length of recessions during the post-war period. There is much pessimism on how long this recession would last as well. According to the OECD, for most countries "a recovery to at least the trend growth rate is not expected before the second half of 2010 implying that the downturn is likely to be the most severe since the early 1980s, leading to a sharp rise in unemployment.”

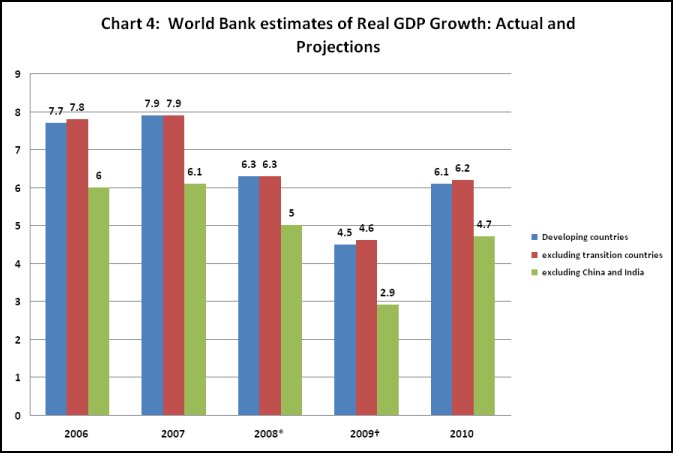

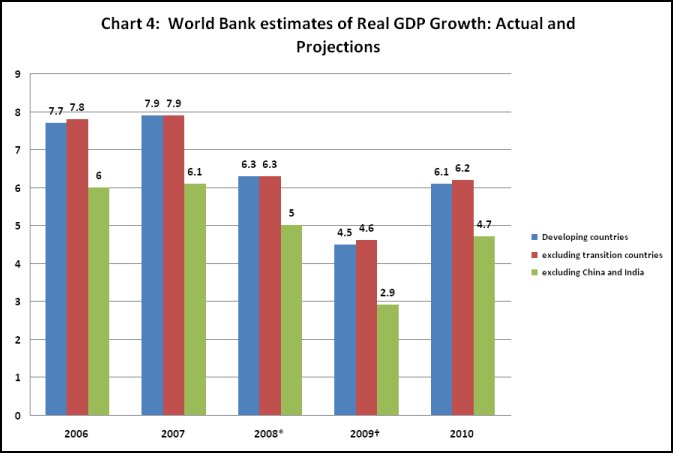

In fact, differential in the distribution of the impact of the recession and a recovery in 2010 are the only positive elements in analyst predictions. Most predictions, as for example that of the World Bank, hold that the decline in growth rates in emerging markets would be much less than in the US. Thus, growth in developing countries as a whole is expected to fall from 6.3 percent in 2008 to 4.5 per in 2009, only to recover to 6.1 per cent in 2010. This is mainly due to China and India without which the figures are more disappointing, but still relatively creditable 5, 2.9 and 4.7 per cent respectively. (Chart 4). In fact, expectations now are generally that developing countries would grow at relatively high rates in normal times. Thus, Hans Timmer, who directs the bank’s international economic analyses and projections is reported to have declared: “You don’t need negative growth in developing countries to have a situation that feels like a recession.”

However, even here, the numbers are proving to be disconcerting. China’s growth has been slipping even if still relatively high. But nobody can ignore the fact that manufacturing, which is the engine of growth in that country is hugely dependent on exports to developed country markets, especially the US. Second, according to Bank of Korea estimates, South Korea’s economy will contract in the last quarter of 2008 and grow at its slowest pace in 11 years in 2009. According to its estimates, the economy, the fourth largest in Asia, would shrink by 1.6 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2008, and grow only at 2 per cent in 2009, and 3.7 per cent for full 2008. And the month-on-month annual rate of growth of India’s Index of Industrial Production fell by 0.4 per cent in October, for the first time in 15 years.

These developments make predictions of a significant growth recovery in 2010 appear optimistic. A question that troubles analysts is how long this recession will last. The recovery assessments are based on the assumptions that the crisis in financial markets would be resolved soon and that there would be no negative feedback loops both between the real sector and the financial sector (which would exacerbate the financial crisis) and within the real sector (which would intensify the crisis in the real economy), before the positive effects of intervention by governments materialize in full. Such assumptions are indeed tenuous, increasing the lack of certainty about a recovery. Thus, job losses in the US are increasing the number of housing foreclosures. Around 7 per cent of mortgage loans were reported to be in arrears in the third quarter, and another 3 per cent are at some stage of the foreclosure process. According to the Mortgage Bankers’ Association, about 2.2 million homes will have entered foreclosure proceedings by the end of this year. This would intensify the financial crisis as well as dampen consumer spending, and could worsen the downward spiral.

Yet, unemployment figures suggest that at the moment the recession is only intensifying. On December 5, 2008, the Bureau of Labour Statistics in the US reported that employers had reduced the number of jobs in their facilities by 533,000, taking the unemployment rate in the US to 6.7 per cent. This reduction—which is the highest monthly fall in 34 years—comes after job losses of 320,000 in October and 403,000 in September.

Total job losses through 2008 are 1.9 million. This means that the 2.5 million jobs that President-elect Obama is promising to deliver through his fiscal stimulus package would just about recover the jobs lost during the recessionary period preceding his swearing in, and leave untouched the backlog of unemployed and those entering the labour force during this period.

While 2008 was the year of crisis, the origins of this crisis go back to the middle of 2007 when evidence that homeowners who had borrowed to finance the property they purchased had begun defaulting on their debt. Soon it became clear that too many people with limited or poor creditworthiness had been induced to borrow large sums by banks eager to exploit the large amounts of liquidity and the low level of interest rates in the system. An unsustainable proportion of defaults seemed inevitable. What was disconcerting in the events that followed was that this “sub-prime” problem soon spread and created a systemic crisis that soon bankrupted a host of mortgage finance companies, banks, investment banks and insurance companies, including big players like Bear Sterns, Lehman Brothers and AIG.

The reasons this occurred are now well known. The increase in sub-prime credit occurred because of the complex nature of current-day finance that allows an array of agents to earn lucrative returns even while transferring the risk. Mortgage brokers seek out and find willing borrowers for a fee, taking on excess risk in search of volumes. Mortgage lenders finance these mortgages not with the intention of garnering the interest and amortization flows associated with such lending, but because they can sell these mortgages to Wall Street banks. The Wall Street banks buy these mortgages because they can bundle assets with varying returns to create securities with differing probability of default that are then sold to a range of investors such as banks, mutual funds, pension funds and insurance companies. Needless to say, institutions at every level are not fully rid of risks but those risks are shared and rest in large measure with the final investors in the chain. And unfortunately all players were exposed to each other and to these toxic assets. When sub-prime defaults began this whole structure collapsed leading to a financial crisis of giant proportions.

The crisis had a number of consequences in the developed countries. It made households whose homes were now worth much less more cautious in their spending and borrowing behavior, resulting in a collapse of consumption spending. It made banks and financial institutions hit by default more cautious in their lending, resulting in a credit crunch that bankrupted businesses. It resulted in a collapse in the value of the assets held by banks and financial institutions, pushing them into insolvency. All this resulted in a huge pull out of capital from the emerging markets: Net private flows of capital to developing countries are projected to decline to $530 billion in 2009, from $1 trillion in 2007. The effects this had on credit and demand combined with a sharp fall in exports, to transmit the recession to developing countries. All of these effects soon translated into a collapse of demand and a crisis in the real economy with falling output and rising unemployment. This is only worsening the financial crisis even further.

A crisis of this nature requires holes to be plugged at many places simultaneously. While there is wide agreement that what is needed is a globally coordinated and huge fiscal stimulus, the actual effort on the ground remains fragmented and meagre. Because of this results are disappointing, threatening to make this crisis the most protracted in a long time. Year 2008 is likely to be remembered as a year in which a crisis of immense proportions unfolded.

Other projections are even more pessimistic. Chapter 1 of the UN’s World Economic Situation and Prospects 2009, released in advance at the Doha Financing for Development conference, estimates that the rate of growth of world output which fell from 4.0 per cent in 2006 to 3.8 per cent in 2007 and 2.5 per cent in 2008 is projected to fall to -0.5 per cent in 2009 as per its baseline scenario and as much as -1.5 per cent in its pessimistic scenario.

Finally, the recently released preliminary edition of the OECD’s Economic Outlook for end-2008 shows that GDP in most OECD countries declined in the third quarter and is likely to fall also in the fourth (Chart 2). In the event, GDP growth in the OECD area which fell from 3.1 per cent in 2006 to 2.6 per cent in 2007 and 1.4 per cent in 2008 is projected to fall to -0.4 per cent in 2009 (Chart 3), and the unemployment rate which rose from 5.6 per cent to 5.9 per cent between 2007 and 2008 is expected to climb to 6.9 per cent in 2009 and 7.2 per cent in 2010.

If these predictions turn out to be true, the prognosis is that what was a recession in 2008 could turn into a depression in 2009. Looking back, 2008 was a year when the recession unfolded. The recession in the US, reports indicate, is not recent but about a year old and ongoing. Short term indicators are disconcerting, but do not convey the real picture. Preliminary estimates of GDP growth in the United States during the third quarter of 2008 point to decline of half a percentage point. But GDP growth during the previous two quarters was positive at 2.8 and 0.9 per cent respectively. The only other quarter since early 2002 when growth was negative was the fourth quarter of 2007. Thus, going by the popular definition of a recession-two consecutive quarters of decline in real gross domestic product-the US is still to slip into recessionary contraction.

But the independent agency which is the more widely accepted arbiter of the cyclical position of the US economy is the Business Cycle Dating Committee of the National Bureau of Economic Research. This committee, which adopts a more comprehensive set of measures to decide whether or not the economy has entered a recessionary phase, has recently announced that the recession in the US economy had begun as early as December 2007. That already makes the recession 11 months long, which has been the average length of recessions during the post-war period. There is much pessimism on how long this recession would last as well. According to the OECD, for most countries "a recovery to at least the trend growth rate is not expected before the second half of 2010 implying that the downturn is likely to be the most severe since the early 1980s, leading to a sharp rise in unemployment.”

In fact, differential in the distribution of the impact of the recession and a recovery in 2010 are the only positive elements in analyst predictions. Most predictions, as for example that of the World Bank, hold that the decline in growth rates in emerging markets would be much less than in the US. Thus, growth in developing countries as a whole is expected to fall from 6.3 percent in 2008 to 4.5 per in 2009, only to recover to 6.1 per cent in 2010. This is mainly due to China and India without which the figures are more disappointing, but still relatively creditable 5, 2.9 and 4.7 per cent respectively. (Chart 4). In fact, expectations now are generally that developing countries would grow at relatively high rates in normal times. Thus, Hans Timmer, who directs the bank’s international economic analyses and projections is reported to have declared: “You don’t need negative growth in developing countries to have a situation that feels like a recession.”

However, even here, the numbers are proving to be disconcerting. China’s growth has been slipping even if still relatively high. But nobody can ignore the fact that manufacturing, which is the engine of growth in that country is hugely dependent on exports to developed country markets, especially the US. Second, according to Bank of Korea estimates, South Korea’s economy will contract in the last quarter of 2008 and grow at its slowest pace in 11 years in 2009. According to its estimates, the economy, the fourth largest in Asia, would shrink by 1.6 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2008, and grow only at 2 per cent in 2009, and 3.7 per cent for full 2008. And the month-on-month annual rate of growth of India’s Index of Industrial Production fell by 0.4 per cent in October, for the first time in 15 years.

These developments make predictions of a significant growth recovery in 2010 appear optimistic. A question that troubles analysts is how long this recession will last. The recovery assessments are based on the assumptions that the crisis in financial markets would be resolved soon and that there would be no negative feedback loops both between the real sector and the financial sector (which would exacerbate the financial crisis) and within the real sector (which would intensify the crisis in the real economy), before the positive effects of intervention by governments materialize in full. Such assumptions are indeed tenuous, increasing the lack of certainty about a recovery. Thus, job losses in the US are increasing the number of housing foreclosures. Around 7 per cent of mortgage loans were reported to be in arrears in the third quarter, and another 3 per cent are at some stage of the foreclosure process. According to the Mortgage Bankers’ Association, about 2.2 million homes will have entered foreclosure proceedings by the end of this year. This would intensify the financial crisis as well as dampen consumer spending, and could worsen the downward spiral.

Yet, unemployment figures suggest that at the moment the recession is only intensifying. On December 5, 2008, the Bureau of Labour Statistics in the US reported that employers had reduced the number of jobs in their facilities by 533,000, taking the unemployment rate in the US to 6.7 per cent. This reduction—which is the highest monthly fall in 34 years—comes after job losses of 320,000 in October and 403,000 in September.

Total job losses through 2008 are 1.9 million. This means that the 2.5 million jobs that President-elect Obama is promising to deliver through his fiscal stimulus package would just about recover the jobs lost during the recessionary period preceding his swearing in, and leave untouched the backlog of unemployed and those entering the labour force during this period.

While 2008 was the year of crisis, the origins of this crisis go back to the middle of 2007 when evidence that homeowners who had borrowed to finance the property they purchased had begun defaulting on their debt. Soon it became clear that too many people with limited or poor creditworthiness had been induced to borrow large sums by banks eager to exploit the large amounts of liquidity and the low level of interest rates in the system. An unsustainable proportion of defaults seemed inevitable. What was disconcerting in the events that followed was that this “sub-prime” problem soon spread and created a systemic crisis that soon bankrupted a host of mortgage finance companies, banks, investment banks and insurance companies, including big players like Bear Sterns, Lehman Brothers and AIG.

The reasons this occurred are now well known. The increase in sub-prime credit occurred because of the complex nature of current-day finance that allows an array of agents to earn lucrative returns even while transferring the risk. Mortgage brokers seek out and find willing borrowers for a fee, taking on excess risk in search of volumes. Mortgage lenders finance these mortgages not with the intention of garnering the interest and amortization flows associated with such lending, but because they can sell these mortgages to Wall Street banks. The Wall Street banks buy these mortgages because they can bundle assets with varying returns to create securities with differing probability of default that are then sold to a range of investors such as banks, mutual funds, pension funds and insurance companies. Needless to say, institutions at every level are not fully rid of risks but those risks are shared and rest in large measure with the final investors in the chain. And unfortunately all players were exposed to each other and to these toxic assets. When sub-prime defaults began this whole structure collapsed leading to a financial crisis of giant proportions.

The crisis had a number of consequences in the developed countries. It made households whose homes were now worth much less more cautious in their spending and borrowing behavior, resulting in a collapse of consumption spending. It made banks and financial institutions hit by default more cautious in their lending, resulting in a credit crunch that bankrupted businesses. It resulted in a collapse in the value of the assets held by banks and financial institutions, pushing them into insolvency. All this resulted in a huge pull out of capital from the emerging markets: Net private flows of capital to developing countries are projected to decline to $530 billion in 2009, from $1 trillion in 2007. The effects this had on credit and demand combined with a sharp fall in exports, to transmit the recession to developing countries. All of these effects soon translated into a collapse of demand and a crisis in the real economy with falling output and rising unemployment. This is only worsening the financial crisis even further.

A crisis of this nature requires holes to be plugged at many places simultaneously. While there is wide agreement that what is needed is a globally coordinated and huge fiscal stimulus, the actual effort on the ground remains fragmented and meagre. Because of this results are disappointing, threatening to make this crisis the most protracted in a long time. Year 2008 is likely to be remembered as a year in which a crisis of immense proportions unfolded.

©

MACROSCAN 2008