Themes > Features

26.12.2009

Cloud over Islamic Banking

When

Dubai World decided to suspend payments on its $26 billion debt, among

the loans involved was a $4.05 billion repayment on a $3.52 billion

sukuk or Islamic bond issue. This presence of an instrument that has

gained some prominence in recent times has questioned the credibility

of the rapidly expanding field of Islamic commercial and investment

banking. The distinguishing feature of this sector of finance is the

generation of assets which are structured to be Islamic law or sharia-compliant.

The sharia bans usury or the charging of interest (riba) on money lent

to others. The issue then is to find alternative routes to ensuring

a margin between the cost of funds and the return they earn to cover

intermediation costs and make a profit.

One obvious way in which this can be done is for the provider of funds

to acquire an asset required by a potential borrower and then to ''lease''

the asset to her. Through periodic lease payments, the lessee compensates

the lessor for an amount equal to the capital outlayed and an interest-margin

equivalent. At the end of the required period the asset is transferred

to the lessee. Another possibility is the sale of an asset on a deferred

payment basis by the lender who then buys it back immediately for a

discount. That is, the client buys an asset from a financial institution

at a marked-up price that is to be paid at a later date, and then sells

the asset to the bank at a lower price to raise finance. The transfer

of ownership of an asset in both transactions ostensibly serves to establish

that the arrangement does not amount to lending money to earn interest.

Islamic bonds or sukuks are also structured along these lines. As opposed

to a normal bond which is a promise to repay a loan, the sukuk confers

partial ownership in an asset or business. This kind of transaction

normally involves a real asset that backs the provision of funds, and

is therefore considered safer, even if not completely safe. In fact,

when the crisis of 2008 broke and the world was experiencing a credit

crunch, the small Islamic finance segment was seen as having weathered

the storm because of its very different practices. That judgment, however,

has been questioned in the wake of the Dubai World payments suspension.

Methods

such as these to earn a return on money without formally charging ''interest''

amount to circumventing the sharia rather than adhering to it. This

is easier because of variations of interpretations of the law between

a more liberal Islamic country like Malaysia and a more orthodox one

like Saudi Arabia—a difference that is not neutralised by the existence

of industry bodies like the Islamic Financial Services Board that is

expected to evolve and set standards for these products. However, the

process of identifying certain products as sharia-compliant is rendered

credible by having a select group of scholars with the necessary knowledge

of Islamic law to vet the instruments created as part of the burgeoning

field of Islamic finance. Assets cleared by this elite group can then

be bought by investors wanting to make sharia-compliant investments.

Islamic finance has a long history, but burgeoned in the 1970s when

the oil shocks increased surpluses held by governments and corporations

in the West Asian region with religiously inclined states and investors.

Moreover, realizing that investors from this region would prefer to

invest in such religiously rated bonds, the world's financial firms

decided to enter this field. And in periods when credit in normal markets

was stretched, even otherwise staid borrowers chose to enter Islamic

financial markets to raise funds. In the process Islamic finance got

integrated with modern finance. According to The Banker's 2009 survey

of the top 500 Islamic financial institutions, ''The volume of sharia-compliant

assets of the Top 500 grew by an extremely healthy 28.6%, rising to

$822bn from $639bn in 2008. At a time when asset growth in the Top 1000

World Banks slumped to 6.8% from 21.6% the previous year, Islamic institutions

were able to maintain the 28% annual compound growth achieved in the

past three years.'' Underlying this growth was a certain distribution

of the world's surpluses and an assessment of the relative safety of

instruments generated by Islamic finance.

It is true that this sector is still a small segment of current finance

and is still substantially confined to dominantly Muslim countries.

Iran, Saudi Arabia and Malaysia are the three leading countries in terms

of sharia-compliant banking assets and Bahrain, Kuwait and Malaysia

are the leaders in terms of Islamic finance institutions. But the rapid

growth in this sector has seen the entry of unusual players both in

terms of financial engagement and in terms of borrowing. Most banks

and non-bank financial institutions have Islamic banking divisions.

These players from the world of conventional finance come armed with

the ability to generate unusual (and risky) derivative assets, which

they then apply to generating sharia-compliant instruments. In the event,

even though West Asia remains the centre of Islamic banking, investors

and borrowers from that region are increasingly turning to the City

of London to exploit its ability to develop opaque products. Even the

US is now host to a large number of institutions involved in activities

linked to Islamic finance.

Once the metropolitan centres of finance also establish themselves as

centres of Islamic finance, borrowers from the rest of the world who

would normally abjure these kinds of instruments and transactions choose

to both invest and borrow in these markets. The attraction is strong

for those seeking to tap the surplus funds of oil-rich Muslim nations.

But the opportunities are not restricted to West Asia, since well-to-do

Muslims with investible surpluses are geographically widely distributed.

General Electric was the first western conglomerate to exploit this

opportunity by issuing Islamic bonds. It has been followed by Tesco

of the UK and Toyota of Japan among others. Governments too—such as

those of Thailand and South Korea—have expressed interest in mobilising

money using such instruments.

It was this asymmetry wherein conventional finance cannot service the

demand for sharia-compliant investments, but conventional borrowers

can issue sharia-compliant bonds and conventional investors can choose

to park their money in such instruments that led to the belief that

Islamic finance had a great future. Moreover, in terms of stock, Islamic

finance accounts for less than 1 per cent of all extant financial instruments.

Finally, the rapidly growing emerging markets are the regions where

a majority of the world's Muslim population lives. Their demand for

assets to invest in is likely to increase if emerging market growth

returns to pre-crisis levels. The potential for growth therefore seems

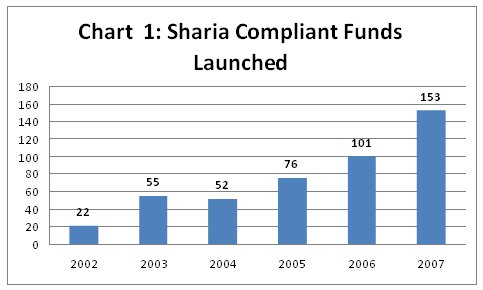

immense. And recent rates of increase in the volume of such instruments

validate these expectations.

However, here were adequate grounds to be sceptical. One factor that

constrains the growth of this sector is higher cost resulting from the

multiple transactions that typically have to be executed to make an

arrangement sharia-compliant. Instruments constituted on that basis

involve higher transaction costs and higher interest rates, making them

uncompetitive. Moreover, if transactions have to be linked to assets

to keep them within the bounds of Islamic law, the proliferation characteristic

of derivative financial instruments that feed on themselves is not possible.

In addition to this, there is the problem that sharia-compliant investors

are expected to avoid patronising institutions that have borrowed too

much, as is the case with most highly leveraged modern financial firms.

However, the sheer need for an adequate volume of assets to meet the

investment needs of those wishing to be sharia-compliant may have encouraged

dilution of character to permit expansion of the volume of these assets.

Such dilution may be facilitated by the shift of Islamic banking at

the margin away from more orthodox Muslim countries to more liberal

ones. According to a Standard & Poor's estimate quoted by the Financial

Times, about 45 per cent of all Islamic bond issues between January

and July of 2009 took place in Kuala Lumpur, way above Saudi Arabia's

22 per cent. They helped raise $9.3bn and put Malaysia on top of the

global league table for issuance.

The ''capture'' of Islamic banking by the now-discredited world of modern

finance with its abstruse products, speculative practices and unwarranted

bonuses has meant that Islamic finance merely mimics conventional finance.

Products existing in not-so-ordinary financial markets are dressed up

to be sharia-compliant. The industry has in the process courted controversy.

One example quoted by the Financial Times (December 7, 2009) was a statement

by Sheikh Taqi Usmani, a respected member of the group of scholars accepted

as certifiers of sharia-compliant instruments that ''many Islamic bonds

went too far in mimicking conventional, interest-paying bonds, which

are banned by Islam.'' So influential was this remark that it triggered

a downturn in the Islamic debt market, possibly because of fears about

redemption of investments that get identified as non-Islamic.

But it is not just the degree of adherence to Islamic tenets that is

a problem with these assets. An additional problem is that with the

industry mimicking conventional finance it has imported all of the problems

typical of modern finance. This tendency has been aggravated by the

requirement that Islamic banking transaction must be based on assets.

Players with oil to sell are unlikely to borrow on the basis of that

commodity. But accumulated capital assets are limited in many countries

where Islamic banking is popular. Thus often the assets that commonly

underlie Islamic financial instruments are real estate and equity, which

can display volatile movements in value. This increases the probability

of default because of speculative decisions. Dubai World would by no

means be the first instance of default, if that occurs. Others like

US-based East Cameron Partners, the Kuwaiti company Investment Dar,

and the Saudi Arabian Saad Group have defaulted in the past, on debts

which include those raised through issues of sukuks. In fact, three

among the largest issues of Islamic bonds in countries belonging to

the Gulf Cooperation Council are in various stages of default.

This implies that the presumption that these Islamic bonds are safer

because they have to be backed by assets is not really true. One problem

is that even when assets are involved, they may have been just accommodated

to meet sharia requirements, in ways that leave investors little recourse

to the assets. Another can be that the assets involved may prove worthless

when sought to be liquidated. This is what seems to be happening in

the case of Dubai World, and its developer arm Nakheel, where the assets

concerned are reclaimed shorelines or strips of desert which were to

be transformed into some version of Paradise on Earth to satisfy the

whims of the wealthy. When the crisis shrank the surpluses of the wealthy,

there were no takers for the part constructed real estate assets, rendering

them almost worthless. The resulting losses forced Dubai World to declare

that it was not in a position to redeem its promises to pay. That not

only hurt investors. It also questioned the credibility of the recent

and rapidly growing versions of what has been presented as Islamic finance.

©

MACROSCAN 2009