Themes > Features

01.12.2010

Surviving Uncertain Times

There's

really no question about it: the world economy is heading for a period

of great economic uncertainty, in which instability, trade and currency

conflicts and possibilities of economic stagnation all loom large. This

reflects the absence of a global economic leader willing and able to

fulfil the roles identified by Charles Kindleberger: discounting in

crisis; countercyclical lending to countries affected by private investors'

decisions; and providing a market for net exports of the rest of the

world, especially those countries requiring it to repay debt. For obvious

reasons, the US cannot currently do these, and there is no evident alternative.

That is why co-ordination is so critical right now for international

capitalism, and why its absence will definitely be felt.

Governments

of both developed and developing countries seem to be caught between

the (often self-imposed) rock of fiscal consolidation created by the

hysteria of bond market vigilantes and the financial media, and the

hard place created by the unwillingness to give up what is clearly an

outdated growth model. As a result, we are faced with the worst of all

economic outcomes in terms of socially fraught stagnation in the North

and ecologically destructive and fragile expansion in the South, with

workers everywhere getting even worse off than before.

There are three major imbalances that continue to characterise the global

economy: the imbalance between finance and the real economy; the macroeconomic

imbalances between major economies; and the ecological imbalance created

by the pattern of economic growth. While these are obviously unsustainable,

the very process of their correction will necessarily have adverse effects

on current growth trajectories.

As it happens, the US current account deficit is already under correction:

the current account deficit in 2009 was just above half its 2008 level,

and the data for this year suggest that it will stay at around that

level. For the rest of the world, it does not really matter whether

the reduction occurs through currency movements or trade protectionism

or domestic economic contraction: the point is that some other engine

of growth has to be found.

Curiously, the governments of the major economies in the global system,

including G20, do not seem to have grasped this. The rather obvious

point that all countries cannot use net export growth as the route to

expansion does not seem to have been understood; so, all governments

think they can export their way out of trouble. This will have inevitable

implications for trade and currency wars, and the likelihood of global

economic stagnation.

So, how well is the Indian economy likely to cope in the near future,

and how will the population as a whole fare in these uncertain times?

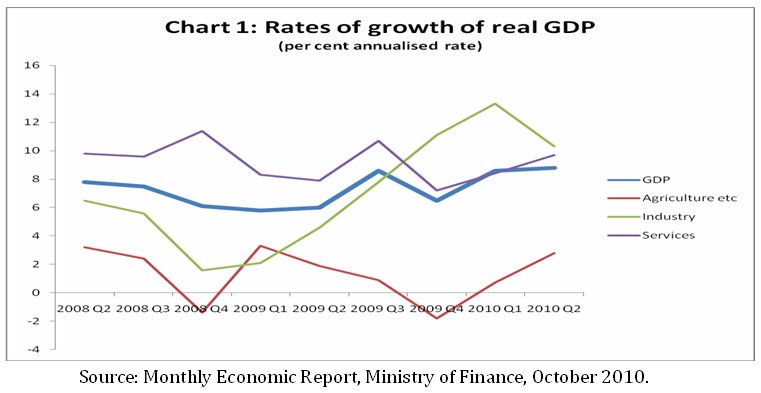

There has been much celebration in the financial media in India about

how well we have weathered the Great Recession, and certainly the output

indicators (Chart 1) are impressive in the overall global context. Despite

poor agricultural performance, rates of growth of aggregate GDP have

remained high because of continued high growth in services and significantly

accelerated growth of industry (dominantly manufacturing).

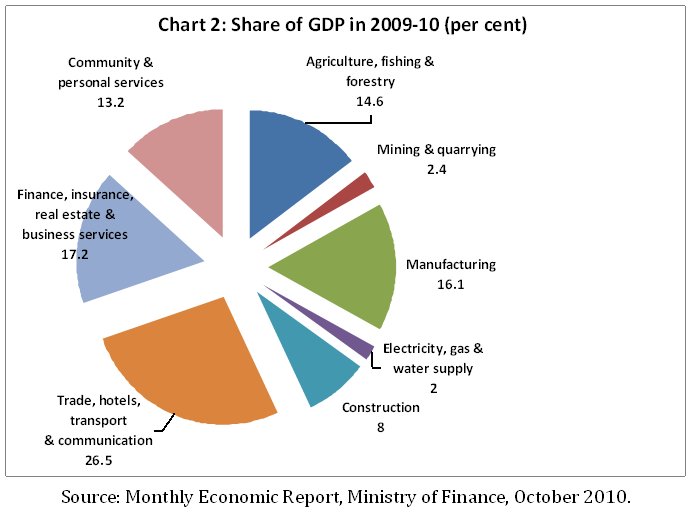

However, the recent pattern of growth has in general been so heavily skewed towards certain services that it has created an apparently unbalanced economy (Chart 2). Agriculture and other primary activities account for less than 15 per cent of GDP, even though they continue to employ well over half the workforce in what is obviously mostly low-productivity activity. Manufacturing has remained stable, and relatively small in output and even smaller in employment. However, the newer services that now dominate the GDP do not employ too many people either, so that most other workers are engaged in low remuneration services. Meanwhile, the FIRE sector (finance, insurance, real estate, and business services) has been growing rapidly and now accounts for an even higher share of GDP than manufacturing – a sure sign of a bubble economy.

So

this means that we are back to the same unsustainable pattern of growth

that generated the images of ''India shining'': booms in retail credit

sparked by financial deregulation and enabled by capital inflows. These

have been combined, especially in the wake of the global crisis, with

fiscal concessions to spur consumption among the richest sections of

the population. This has generated a substantial rise in profit shares

in the economy and the proliferation of financial activities, and combined

with rising asset values to enable a continuation of the credit-financed

consumption splurge among the rich and the middle classes along with

debt-financed housing investment.

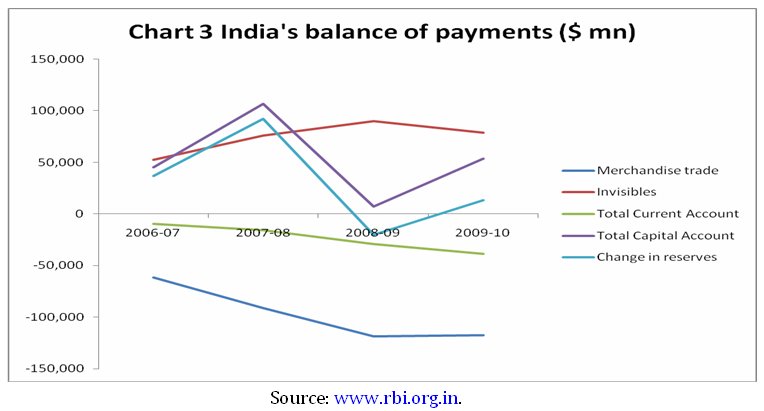

The problem is that this is associated with a balance of payments trajectory

that is fundamentally unsustainable. As Chart 3 shows, it is only the

invisibles account (led by remittances from India workers abroad and

software and related exports) that has kept the balance of payments

from appearing to be even more stark. The trade account shows ever growing

deficits, which are increasingly driven by non-oil imports. Meanwhile,

the large inflows of capital are really being stored up in the form

of foreign exchange reserves, for fear of causing excessive exchange

rate appreciation.

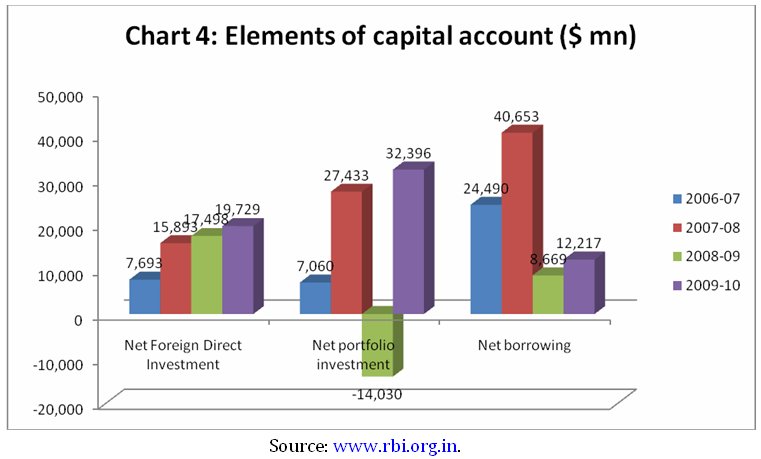

In

fact, after a brief period of reduction, India's place as a currently

favoured destination for internationally mobile capital was reinforced

in the past year. Chart 4 shows how different elements of the captial

account have behaved in recent years. The most rapid post-crisis recovery

has been in portfolio capital, which fell during the crisis year but

surged back to high levels the subsequent year. In fact, the most recent

data (not covered in this chart) indicates a troublesome surge in such

hot money inflows, of more than $70 billion in just a few months – troublesome

because it can lead to an unwanted currency appreciation and because

it can just as easily flow out again.

This

is a problem plaguing several emerging economies, and underlines the

need for capital controls to prevent unwanted inflows of speculative

capital. So much so that even the IMF has started advocating such controls

for developing countries that are being swamped by the ''carry trade''

based on interest rate differentials across economies.

Unfortunately,

our own government seems much less consious of the dangers such inflows

pose, especially for an economy that is clearly in the midst of another

bubble-driven expansion. Instead, Ministers are talking about the economy

being able to absorb at least another $100 billion of capital inflows

– unmindful of the reality that the economy has not even absorbed the

smaller amounts that are currently pouring in, and instead is simply

accumulating reserves.

In

any case, such absorption has to be sustainable, which is why much more

attention is required to improving the trade account. This is going

to be much more difficult in the current global economy, but clearly

the need is for both diversification of trade and more attention to

sustainable expansion of the domestic market.

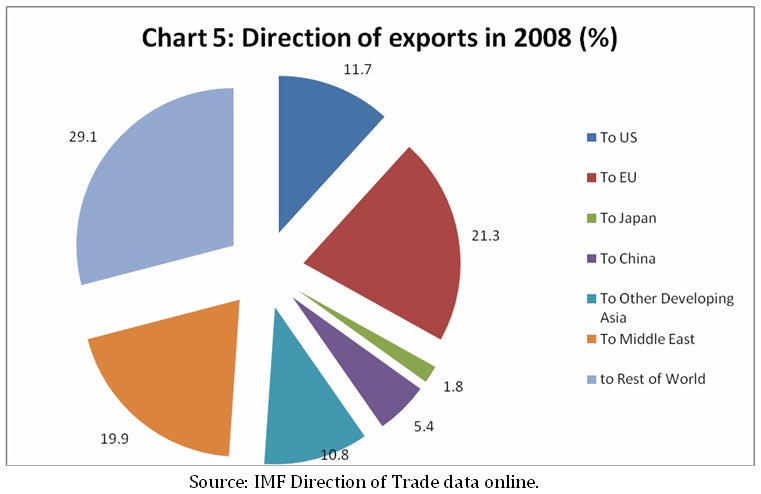

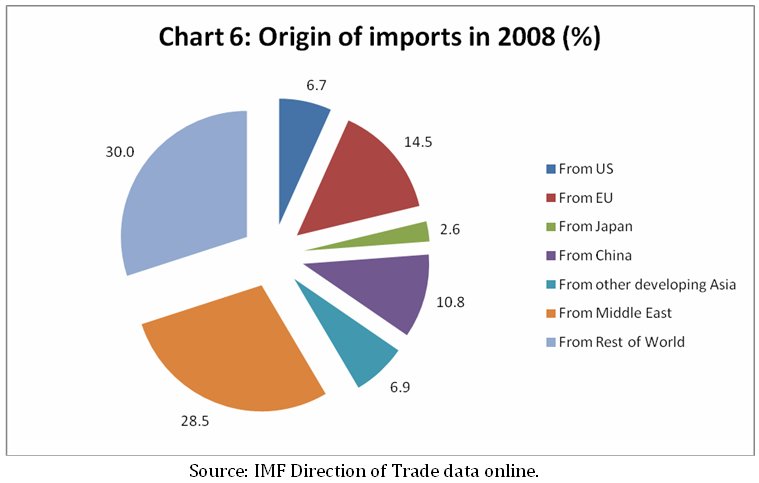

The good news is that on the external trade front there does seem to

have been a significant process of diversification in the past decade,

as Charts 5 and 6 indicate. China is among our largest trading partners

now, though that dominantly consists of India exporting raw materials

and intermediates and importing finished goods from China. The Middle

East has also emerged as a major market, and other areas are playing

increasing roles as well.

However, without sustained expansion of the domestic market, the condition of the bulk of the Indian population will not improve. This really requires increasing the disposable incomes of wage earners and the self-employed, not just a credit-based expansion of demand that is bound to end in tears. But for this, there has to be more official focus on generating both employment and better remuneration. This is actually quite doable, since it can be led by increased public provision of essential goods and services (all of which are employment generating and have high multiplier effects). But for that, we need genuine political will.

©

MACROSCAN 2010