Three months ago, when the Finance Ministry released

its annual assessment of India's external debt position,

the scenario appeared comforting. On the one hand,

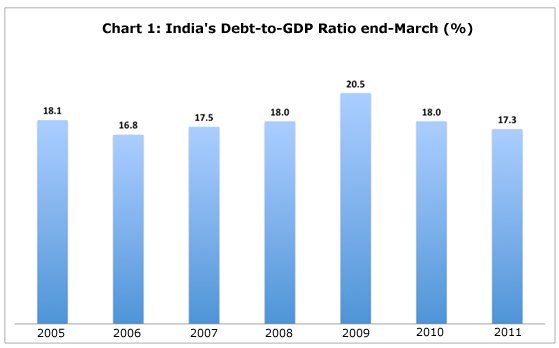

the external debt to GDP ratio, at 17.3 per cent at

the end of March 2011 (Chart 1), was well within limits

considered safe. It was lower than in many other countries,

much below where it had been during the 1991 crisis

and below its level in the previous two years. Combine

this with the fact that India has accumulated considerable

foreign exchange reserves to cover any bunching of

repayments and external debt does not appear to be

among the country's problem areas.

Chart

1 >> Click

to Enlarge

However,

a closer examination of recent trends suggests that

there may be some cause for concern on the external

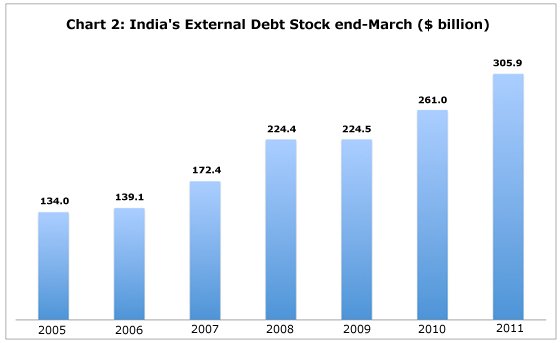

debt front. To start with, in recent years the absolute

volume of external debt has been rising quite sharply,

except for stagnation in crisis-year 2009. The stock

of debt at the end of March rose by $33 billion and

$52 billion in 2007 and 2008 and by $37 billion and

$45 billion in 2010 and 2011 respectively (Chart 2).

Clearly, India's appetite for debt has been increasing.

Chart

2 >>

Click

to Enlarge

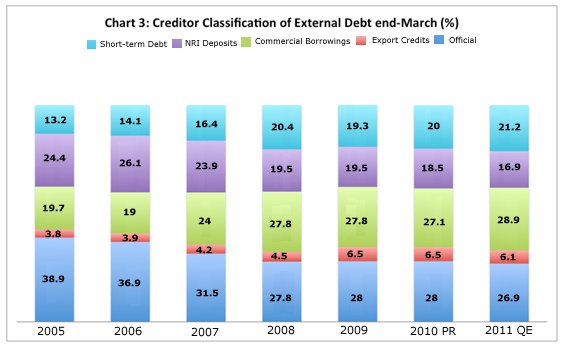

Secondly, as has been known for some time now, India

is being graduated out of official (bilateral and

multilateral) debt, so that the share of private sources

in total debt has been rising significantly. Third,

within these private sources, the share of deposits

from Non-resident Indians seeking to benefit from

differentials in interest rates between the Indian

and global markets has been falling, while that of

external borrowing by domestic entities has increased

from around 20 per cent in 2005 to almost 30 per cent

in 2011 (Chart 3).

Chart

3 >>

Click

to Enlarge

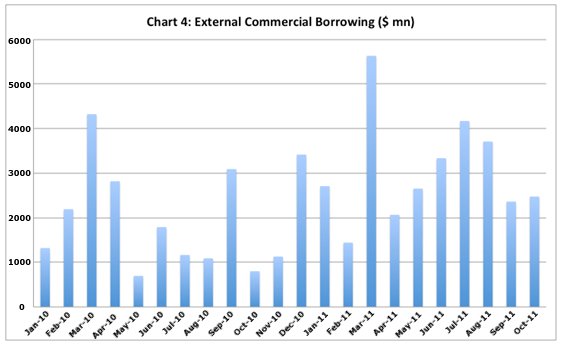

This increasing role for commercial borrowing has

essentially been because of an increase in borrowing

by India firms from international markets. The Reserve

Bank of India releases monthly figures on external

borrowing by Indian corporates through the ‘automatic'

and ‘approval' routes. The most recent figure is for

October 2011. Those figures show that despite month-to-month

fluctuations, external borrowing by these entities

has risen quite sharply from $8.6 billion between

April and October 2010 to $16.4 billion between November

2010 and May 2011, and to $18.7 billion between April

and October 2011 (Chart 4).

Chart

4 >>

Click

to Enlarge

Finally, there has been an increase in short-term

debt in total external borrowing from 13 per cent

to 21 per cent of the total. This may partly reflect

the unwillingness of lenders to increase only their

long-term exposures in a country with a rising appetite

for debt. It may also be because Indian borrowers

are also using the short-term channel to reduce financing

costs, in the belief that they can, if necessary,

roll-over that debt when due.

Thus, the growth in external debt has been substantially

because the Indian corporate sector has stepped up

its commercial borrowing from the international market.

This trend seems to have accelerated in recent times.

Underlying the month-to-month variations in the volume

of borrowing because of the presence or absence of

large individual borrowers, there is evidence of a

continuous rise. To add to this, Indian borrowers

have not shied away from short-term debt either.

Three factors explain this tendency. One is the increased

reliance of the corporate sector on debt (as opposed

to equity) to finance expenditures, and more so on

foreign debt because on average it tends to be much

cheaper. A second obvious cause is the sharp rise

in domestic interest rates. The Reserve Bank of India

has announced around a dozen increases in reference

rates since March last year, raising the cost of credit

provided to the banking system by more than 3 percentage

points. Since this is the rate at which banks can

borrow from the RBI, they in turn are charging higher

rates on loans to their clients. In the event, there

has been a widening of interest rates payable on borrowing

from the domestic and external markets, with the latter

being the cheaper source. When this happens, the normal

tendency would be for firms to borrow abroad to meet

even their domestic expenditures and finance their

expansion plans targeted at the domestic market.

Finally, this tendency has been encouraged by the

willingness of the government to permit such access.

In principle there is a ceiling on aggregate external

commercial borrowing (ECB) set by the government at

each point in time. But not only is that ceiling not

imposed strictly, but the government periodically

revises the ceiling to accommodate increases in private

borrowing. The most recent increase was a $5 billion

hike in the ceiling for both government and corporate

ECB to $15 billion and $45 billion respectively.

This lax attitude has been strengthened by the rise

in domestic interest rates. With evidence that GDP

growth and industrial growth are faltering, the government

and the RBI have been criticised for hurting growth

in an unsuccessful attempt to control inflation by

hiking rates. One way to mute that criticism is to

allow the bigger and more vocal firms to access cheap

resources from the international market by permitting

increased volumes of ECB. Moreover, any increased

inflow of foreign capital, even in the form of debt,

helps to shore up the rupee (which has depreciated

because of the global flight to safety to the dollar

and the recent tendency for foreign investors to exit

from India in the context of increasing trade and

current account deficits in India's balance of payments).

This effect on the rupee must also be motivating the

RBI to facilitate the increase in debt.

There are, however, two much-discussed dangers associated

with this tendency. First, there arises a mismatch

between the currency in which debt service commitments

on external loans must be met and the currency in

which revenues are garnered from the domestic market-oriented

activities that are financed by such loans. Hence,

a part of the foreign exchange earned or acquired

in other activities would have to be diverted to these

borrowers in the future so that they can meet their

debt service commitments. This could put some strain

on the balance of payments.

The second problem is that the borrowers themselves

are taking on substantial exchange rate risks. While

they may be obtaining finance at interest rates lower

than currently charged in the domestic market, their

debt service commitments in rupee terms can rise sharply

if there is a depreciation of the domestic currency.

This could more than neutralise the benefit of an

interest rate differential.

Besides these factors that call for exercise of caution,

another danger is a rise in in rates in international

markets. Those interest rates are low now because

central banks in the developed countries have pumped

large volumes of cheap liquidity into the market in

response to the crisis. But there is no guarantee

that the era of access to cheap liquidity for emerging

markets will continue, as illustrated by the difficulties

being faced by the peripheral countries in the Eurozone.

If international rates rise, efforts to refinance

maturing debt would require expensive borrowing. When

all of this is put together, the rise in external

borrowing, though still within limits, increases the

vulnerability of the corporate sector and the nation.

The government, therefore, would be well-advised to

continue with its policy of limiting external borrowing.

However, under pressure from the corporate sector,

it seems to be inclined towards loosening rules with

respect to external borrowing, to dampen corporate

criticism of the high interest rate regime. In response,

corporates are being offered an escape to cheap credit

through means that increase external vulnerability.

There are conspiracy theories doing the rounds. Rumour

has it that there is a standoff between the Ministry

of Finance and the Reserve Bank of India over interest

rate policy. Given the government's own failure, the

central bank has been forced to take on the burden

of combating inflation, leading to the sharp rise

in interest rates. But since the Finance Ministry

does not seem to like that, it is reportedly using

the ECB lever to counter the impact of the RBI's intervention

on the corporate sector. Whatever the drivers, the

process is increasing external vulnerability.

*

This article was originally published in the Business

Line on 12 December, 2011, and is available at

http://www.thehindubusinessline.com/opinion/columns/c-p-chandrasekhar/

article2709520.ece?homepage=true