Prospects for the World Economy in 2012*

There

is a palpable sense of gloom and impending doom in most discussions

of the world economy today. Even before, several economists had argued

that the excessive optimism about ''V shaped recovery'' that was being

used to describe the economic revival in 2010 was premature and misplaced,

especially as none of the fundamental contradictions of global capitalism

that led to the previous crisis had been adequately addressed. But they

were once again written off as Cassandras by the financial media, which

desperately sought sources of ''good news'' and future engines of growth

particularly among the emerging markets.

Now even the most stalwart establishment voices are expressing growing

concern and pessimism. Oliver Blanchard, Chief Economist at the IMF,

has issued what must be an unprecedentedly sombre and even dismal statement

at the close of the year, noting that recovery is at a standstill in

the advanced economies and recognising that 2012 may face even worse

economic conditions than 2008.

Blanchard refer euphemistically to ''multiple equilibria - self-fulfilling

outcomes of pessimism or optimism, with major macroeconomic implications''

and effectively suggests that unless private expectations are managed

better by decisive government policies, negative expectations will become

self-fulfilling. But it is harder for governments to ''manage expectations'',

because private investors themselves are schizophrenic about government

deficits and economic growth. Financial markets effectively appear to

demand fiscal consolidation by putting very high spreads on the bonds

of governments with high ratios of public debt to GDP or fiscal deficit

to GDP. And then investors in these markets are very surprised (and

react adversely) when attempts at fiscal austerity reduce economic activity

and growth prospects.

This has already created a self-reinforcing cycle of contraction in

the eurozone, and as long as European leaders (and incidentally the

IMF) continue to press for fiscal austerity, this will continue. Meanwhile

the peculiar political configurations in the US make it unlikely that

any real fiscal stimulus will emerge to ensure a more broad-based and

stable economic recovery. The belief currently expressed by many economic

commentators, that a ''big bazooka'' in the form of even looser monetary

policy of the European Central Bank and the US Federal Reserve, will

be sufficient to lift economic activity, is unwarranted.

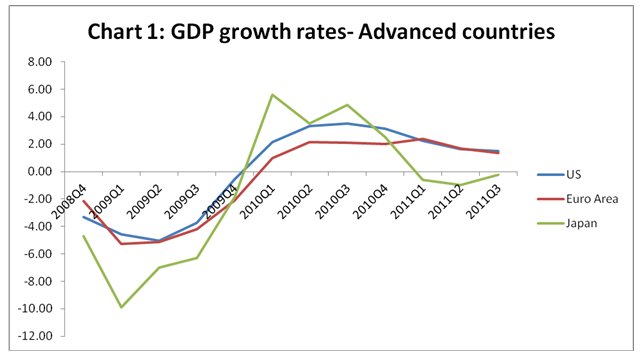

Chart 1 shows quarterly growth data for real GDP since the trough of

the crisis in late 2008. It is evident that Blanchard is completely

correct in noting that the recovery in the major advanced economic regions

is sputtering if not dying. (Data in all charts is based on IMF's Global

Economic Indicators database.) Output growth in Japan has already turned

negative once again in the most recent quarters, while it is sluggish

in the US and likely to become much worse in the euro area given the

inability to resolve the internal problems of the eurozone.

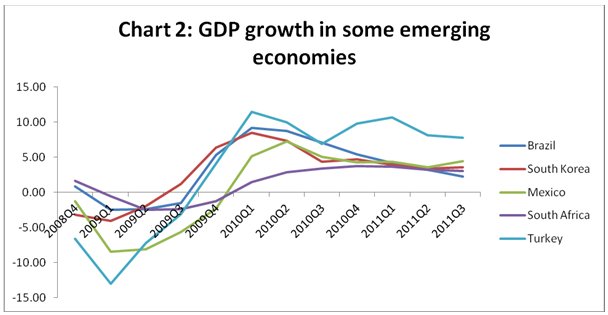

In the past global recession, many developing countries sufffered quite sharp declines in output but then the recovery was also faster and more buoyant. Chart 2 shows a sample of emerging market economies (and does not inlcude China and India about which enough discussion already exists). Real GDP recovered more sharply in the economies that had expereinced the biggest slumps, but despite this, since the middle of 2010 there has been a deceleration in almost all of the economies described here.

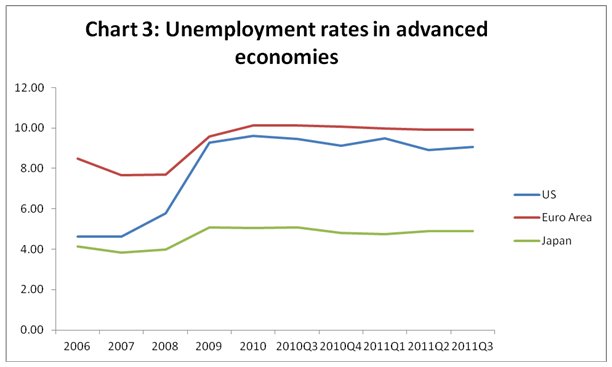

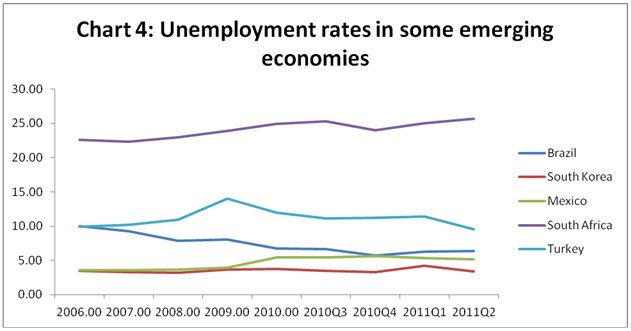

This sluggish recovery or beginning of renewed recession is of major concern not just in itself, but because even the period of recovery was already not associated with much improvement in labour market conditions. Chart 3 shows that in the three major advanced economic regions, open unemployment rates increased during the Great rcession, and since then have remained at these high levels despite subsequent increases in incomes and economic activity. Chart 4 shows that (other than for Turkey and Brazil) a similar process was also under way for the emerging economies considered here.

A September 2011 report from the ILO to the G20 found that in the first

quarter of 2011, only a handful of countries (notably, Argentina, Brazil,

Turkey and Indonesia) had absolute employment levels that were above

the levels of the first quarter of 2008, before the eruption of the

global crisis. In some countries both output and employment were still

below their earlier levels (including the developed world: European

Union, the US and Japan) while in others like South Africa, output had

recovered but employment was still lower than in early 2008. So the

weakening prospects for the world economy come at a time when labour

market conditions are already very fragile across the world.

This is extremely bad news for the developing world. Already, it is

evident that it is misplaced and even foolhardy to hope that economic

expansion in China, Brazil, Russia and some other countries will be

enough to compensate for the slowdown in the advanced economies. In

sheer quantitative terms, total incomes and import demand in these countries

simply cannot counterbalance the falling net demand from US and Europe.

But there are further reasons why developing countries - including those

that are currently being expected to save the world economy - cannot

expect an easy ride in the coming year themselves.

First, most developing regions are directly affected by the slowdown

in import demand from Europe, and to a lesser extent the US. For example,

manufacturing exports from developing Asia, particularly China, are

already affected by the slowdown in Europe and the process is likely

to intensify in the coming months. Second, the reduction in China's

exports affects its own demand, as the complex export production platform

it is the centre of in Asia reduces demand for raw materials and intermediates.

Third, many developing countries have also been affected adversely by

the sudden and rapid outflow of mobile finance capital, as banks and

other financial institutions book their profits in emerging markets

in order to cover their losses. This has also been associated with rapid

depreciation of several emerging market currencies, which causes their

import bill for oil and other essential goods to increase, but not necessarily

affecting their exporting potential in the current climate.

Fourth, there are reasons to be more concerned than many analysts appear

to be, about the immediate prospects for the Chinese economy. As the

housing bubble in China is pricked and real estate prices fall, this

will have negative multiplier effects on all related activities in construction

and so on. The debt deflation associated with falling asset prices may

also affect consumption and employment. So there is a serious internal

threat to growth, unless the Chinese government takes active measures

to revive consumption, without relying on expansion of household debt.

In many other emerging markets, the previous boom was associated with

credit-driven bubbles, and as these are burst, the prospects for economic

expansion will similarly be affected.

So there are good reasons for Blanchard of the IMF and others to be

gloomy about global economic prospects. However, unless they and others

who have real influence on economic policy making across the world argue

for a real change in both economic paradigm and current strategy, things

are unlikely to look up in the coming year.

*

Note: This article was originally

published on 26 December, 2011, in the Business Line, and is available

at:

http://www.thehindubusinessline.com/opinion/columns/c-p-chandrasekhar/

article2749931.ece?homepage=true