The

belief is obviously that reducing such "rigidities"

and curbing the power of organised labour will increase

private investment, increase economic activity and

improve productivity. All these in turn will improve

external competitiveness, which is considered to be

so important these days.

The chief problem with this argument is that it completely

ignores the major forces affecting investment, economic

activity and therefore employment. It is now accepted

across the world that aggregate investment does not

respond to changes in the wage rate, but to broader

macroeconomic conditions such as the level of demand,

the amount of public investment, the expectation of

external markets, and so on.

Labour costs are never viewed in isolation, but only

in relation to labour productivity, which in turn

is affected not only by the level of well-being, skill

and education of the workers themselves, but also

by infrastructure conditions, the technology used

in production, and so on. In such a context, greater

"flexibility" in labour markets might simply

mean the perpetuation of low wage-low productivity

practices by employers, rather than more economic

growth.

While there is a formidable array of rights accepted

by the Indian Constitution for workers, and protective

legislation as well, the problem is that they are

rarely achieved or enforced. Typically they can only

be even minimally enforced in the organised sector.

It is currently being argued by neo-liberal economists

and others, that these laws, which restrict employers'

rights to dismiss workers at will and stipulate some

degree of permanency of employment, act as a major

drag on the profitability of the organised sector

and on its ability to compete with more flexible labour

relations elsewhere. In this perception, a shift towards

a more universal contract-based system of labour relations,

with no assumptions of permanency of employment, is

required to ensure economic progress based on private

enterprise within the current context.

But it can be argued in response to this, that labour

laws are far less significant as factors in affecting

private investment, and therefore employment, than

more standard macroeconomic variables and profitability

indicators. Thus, the condition and cost of physical

infrastructure, the efficiency of workers as determined

by social infrastructure, and the policies which determine

access to credit for fixed and working capital as

well as other forms of access to capital, all play

more important roles in determining overall investment

and its allocation across sectors. Expectations of

demand and the extent of the market determine the

volume of investment.

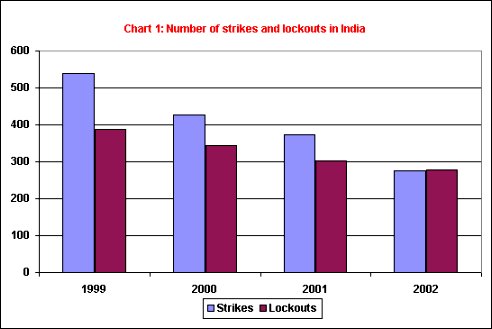

Indeed, it is also clear that in the recent past in

India, strikes have been far less relevant in disrupting

production in the Indian economy, than lockouts by

employers. Chart 1 shows the actual number of strikes

and lockouts in India over the period 1999-2002. While

both have been coming down over this period, the decrease

in the number of strikes has been more dramatic, and

in 2002, the number of lockouts was actually higher.

Chart

1 >> Click

to Enlarge

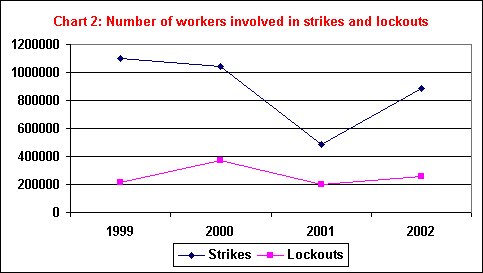

Chart 2 provides information on the number of workers

involved in strikes and lockouts - here, the evidence

is that strikes have involved a greater number of

workers than lockouts. However, obviously strikes

have been of shorter duration and therefore less disruptive

of production and economic activity, as shown by the

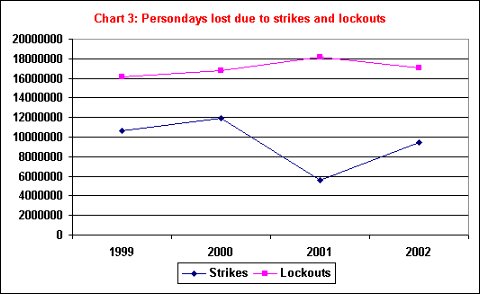

actual working days lost, in Chart 3. The persondays

lost to lockouts has been consistently higher than

the loss due to strikes, and was nearly double in

2002.

Chart

2 >> Click

to Enlarge

Chart

3 >> Click

to Enlarge

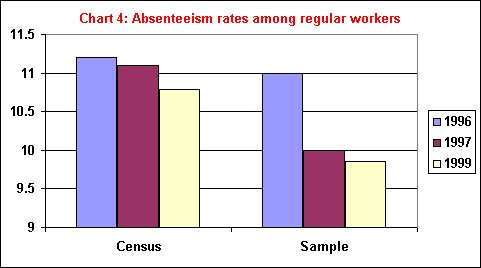

It is also likely that workers' discipline has improved

in general, as absenteeism rates among regular workers

seem to have come down quite drastically in the recent

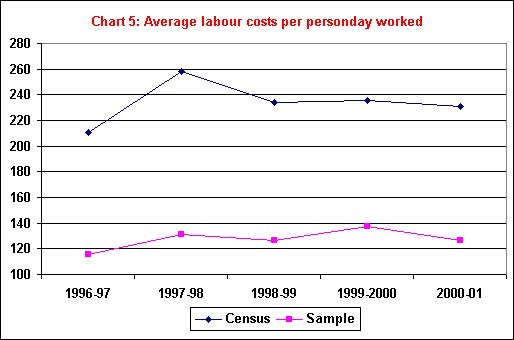

past, as indicated in Chart 4. Similarly, labour costs

per personday worked (Chart 5) have been broadly flat,

despite large increases in labour productivity, so

that obviously workers have not garnered any advantage

from technological progress, the gain from which have

accrued to employers instead.

Chart

4 >> Click

to Enlarge

Chart

5 >> Click

to Enlarge

It is in this context that the right to strike must

be considered in India. Obviously, strikes are ultimate

weapons, which are only resorted to by workers when

all other means of struggle and negotiation have been

exhausted. In recent Indian experience, the working

class as whole has been relatively responsible and

only used strikes in extreme cases when negotiations

have failed completely or when employers have appeared

to be completely insensitive to genuine demands of

labour.

Denial of this right would lead to a massive deterioration

of the bargaining power of workers, which has already

been weakened by various macroeconomic processes such

a global integration and the withdrawal of the state

from important areas of regulation and provision.

In any society, the socio-economic rights of all citizens,

including workers, have never really been freely gifted

by the state or employers; their recognition and implementation

have always been the result of prolonged struggle

on the part of workers and other groups.

Changing the conditions of such struggle amounts to

changing the possibility of ensuring these basic rights,

which are even recognised in the Constitution of India.

Therefore, the right to strike for workers remains

an important instrument for ensuring the basic economic

rights of all citizens.