Themes > Features

4.02.2005

The FII Fest in India's Stock Markets

2004

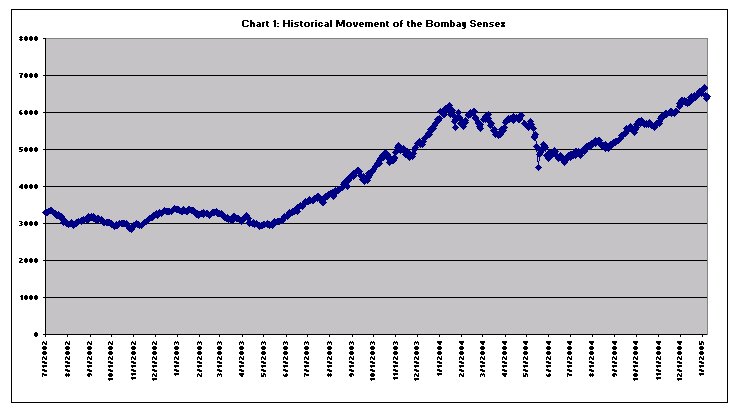

was one more unusual year in India's stock markets. It began with

the Sensex still at a high and above the 6000 mark. It witnessed a

decline to a low in mid-May of around 4500, delivered ultimately with

the market's single day loss of close to 565 points. It then registered

a recovery that turned into a bull run, which took the Sense to 6679

on the first trading day in the new year. And then it witnessed an

abrupt end to the bull run, signalled by a 316-point intra-day decline

in the Sensex on January 5. (Chart 1).

This volatility has been visible in the medium and long term as well.

From a low of 2924 on April 5, 2003, the Sensex had risen to 6194

on January 14, 2004, only to fall to 4505 on May 17, before rising

to close at a peak of 6679 on January 3, 2005. These wild fluctuations

have meant that for those who bought into the market at the right

time and exited at the appropriate moment, the average return earned

through capital gains were higher in 2003 than 2004, despite the extended

bull run in the latter year.

There are two messages

that this experience sends out. The first is that, if market expectations

can turn so whimsically, the signals or rumours on which they are based

must lack any substance since any ''fundamentals'' on which they could

be anchored have not shifted so violently. The second is that there

must be some unusually strong force that is determining movements in

the market which alone can explain the wild swings it is witnessing.

The combination of these two factors is indeed a disconcerting phenomenon,

since if some force has the ability to lead the market and the others

can be taken along without much resistance, the market is in essence

being subjected to manipulation, even if not always consciously. Not

surprisingly, recent market developments have once more focused attention

on the volatility that has come to characterise India's stock markets.

Movements in the Sensex during the two years have clearly been driven

by the behaviour of foreign institutional investors (FIIs), who were

responsible for net equity purchases of as much as $6.6 and $8.5 billion

respectively in 2003 and 2004. These figures compare with a peak level

of net purchases of $3.1 billion as far back as 1996 and net investments

by FIIs of just $753 million in 2002. In sum, the sudden FII interest

in Indian markets in the last two years account for the two bouts of

medium-term buoyancy that the Sensex recently displayed.

At one level this influence of the FIIs is puzzling. The cumulative

stock of FII investment, totalling $ 30.3 billion at the end of 2004,

amounted to just 8 per cent of the $383.6 billion total market capitalisation

on the Bombay Stock Exchange. However, FII transactions were significant

at the margin. Purchases by FIIs of $31.17 billion between April and

December 2004 amounted to around 38.4 per cent of the cumulative turnover

of $83.13 billion in the market during that period, whereas sales by

FIIs amounted to 29.8 per cent of turnover. Not surprisingly there has

been a substantial increase in the share of foreign stockholding in

leading Indian companies. According to one estimate, by end-2003, foreigners

(not necessarily just FIIs) had cornered close to 30 per cent of the

equity in India's top 50 companies — the Nifty 50. In contrast, foreigners

collectively owned just 18 per cent in these companies at the end of

2001 and 22 per cent in December 2002.

A recent analysis by Parthaprathim Pal estimated that at the end of

June 2004, FIIs controlled on average 21.6 per cent of shares in Sensex

companies. Further, if we consider only free-floating shares, or shares

normally available for trading because they are not held by promoters,

government or strategic shareholders, the average FII holding rises

to more than 36 per cent. In a third of Sensex companies, FII holding

of free-floating shares exceeded 40 per cent of the total.

As Table 1, shows matters have not changed significantly more recently.

As of September 2004, which is the last quarter for which information

is available, FII shareholding in the 30 companies included in the Sensex

stood at an average of 19.6 per cent. What is noteworthy, however, is

that this proportion varied from a low of 2.52 per cent to a high of

as much as 54 per cent in the case of Satyam Computers and 63.17 per

cent in the case of HDFC. If FIIs as a group chose to move out of the

stock concerned, a collapse in the price of the equity is inevitable.

Table

1: FII Holding in Sensex Companies End-September 2004 |

|||

FII

Holding |

Total

Stock |

FII

Share |

|

| Associated Cement Companies Ltd. |

40900718 |

178277669 |

22.94 |

| Bajaj Auto |

16330247 |

101183510 |

16.14 |

| Bharti Tele |

221015179 |

1853366767 |

11.93 |

| BHEL |

53591202 |

244760000 |

21.90 |

| Cipla Ltd. |

52682658 |

299870233 |

17.57 |

| Dr.Reddy's Laboratories Ltd. |

12809188 |

76518949 |

16.74 |

| Grasim Industries Ltd. |

19113076 |

91671233 |

20.85 |

| Gujarat Ambuja Cements Ltd. |

41620922 |

179399951 |

23.20 |

| HDFC Bank Ltd. |

76402122 |

286232913 |

26.69 |

| Herohonda M |

46161349 |

199687500 |

23.12 |

| Hindalco IN |

17828040 |

92475275 |

19.28 |

| Hindustan Lever Ltd. |

278289559 |

2201243793 |

12.64 |

| Hindustan Petroleum Corp. Ltd. |

66559789 |

339330000 |

19.62 |

| Housing Development Finance Co |

156482326 |

247703418 |

63.17 |

| I T C Ltd. |

37548907 |

247924902 |

15.15 |

| ICICI Bank Ltd. |

359488564 |

735928149 |

48.85 |

| Infosys Technologies Ltd. - ORDI |

108676702 |

267860670 |

40.57 |

| Larsen & Toubro Ltd. |

24048087 |

129902937 |

18.51 |

| Maruti Udyog |

34644938 |

288910060 |

11.99 |

| Ong Corp Ltd. |

93054697 |

1425933992 |

6.53 |

| Ranbaxy Laboratories Ltd. |

41321691 |

185831140 |

22.24 |

| Reliance |

319138099 |

1396377536 |

22.85 |

| Reliance ENR* |

32896582 |

185572799 |

17.73 |

| Satyam Comp |

171632507 |

317593572 |

54.04 |

| State Bank of India |

60294540 |

526298878 |

11.46 |

| Tata Iron and Steel Co. Ltd. |

66306238 |

553472856 |

11.98 |

| Tata Motors |

76364625 |

358485286 |

21.30 |

| Tata Power |

26069920 |

197897864 |

13.17 |

| Wipro Ltd. |

17630021 |

698951673 |

2.52 |

| Zee Telef Lt |

154980521 |

412505012 |

37.57 |

| Total Sensex Cos |

2723883014 |

14321168537 |

19.02 |

Table 2, which provides the frequency distribution of Sensex companies according to the size class of FII shareholding proportions at the end of the first three quarters of 2004, suggests that FIIs do shift in and out of particular shares, just as they are known to shift in and out of particular markets. Between end-March and end-June FIIs were reducing their exposure in Sensex companies, wheras by end-September they had once again begun to increase their exposure. If at the end of June there were 5 companies in which the share of FIIs in total equity was less than 10 per cent, this figure had fallen to 2 by end-September, whereas the number of firms in which FII exposure was 10-20 per cent had risen from 12 to 14 and those with 20-30 per cent exposure from 8 to 9. Given the short period in which this had occurred and the small proportion of floating shares in the case of many companies, these changes are indeed significant.

Table 2: Frequency Distribution of FII Holdings in Sensex Companies |

|||

March 2004 |

June 2004 |

September 2004 |

|

| < 10 per cent |

3 |

5 |

2 |

| 10-20 per cent |

13 |

12 |

14 |

| 20-30 per cent |

9 |

8 |

9 |

| 30-40 per cent |

1 |

2 |

2 |

| > 40 per cent |

4 |

3 |

3 |

Given

the presence of foreign institutional investors in Sensex companies

and their active trading behaviour, their role in determining share

price movements must be considerable. Indian stock markets are known

to be narrow and shallow in the sense that there are few companies whose

shares are actively traded. Thus, although there are more than 4700

companies listed on the stock exchange, the BSE Sensex incorporates

just 30 companies, trading in whose shares is seen as indicative of

market activity. This shallowness would also mean that the effects of

FII activity would be exaggerated by the influence their behaviour has

on other retail investors, who, in herd-like fashion tend to follow

the FIIs when making their investment decisions.

These features of Indian stock markets induce a high degree of volatility

for four reasons. In as much as an increase in investment by FIIs triggers

a sharp price increase, it would provide additional incentives for FII

investment and in the first instance encourage further purchases, so

that there is a tendency for any correction of price increases unwarranted

by price earnings ratios to be delayed. And when the correction begins

it would have to be led by an FII pull-out and can take the form of

an extremely sharp decline in prices.

Secondly, as and when FIIs are attracted to the market by expectations

of a price increase that tend to be automatically realised, the inflow

of foreign capital can result in an appreciation of the rupee vis-à-vis

the dollar (say). This increases the return earned in foreign exchange,

when rupee assets are sold and the revenue converted into dollars. As

a result, the investments turn even more attractive triggering an investment

spiral that would imply a sharper fall when any correction begins.

Thirdly, the growing realisation by the FIIs of the power they wield

in what are shallow markets, encourages speculative investment aimed

at pushing the market up and choosing an appropriate moment to exit.

This implicit manipulation of the market if resorted to often enough

would obviously imply a substantial increase in volatility.

Finally, in volatile markets, domestic speculators too attempt to manipulate

markets in periods of unusually high prices. Thus, most recently, the

SEBI is supposed to have issued show cause notices to four as-yet-unnamed

entities, relating to their activities on around Black Monday, May 17,

2004, when the Sensex recorded a steep decline to a low of 4505.

All this said, the last two years have been remarkable because, even

though these features of the stock market imply volatility; there have

been more months when the market has been on the rise rather than on

the decline. This clearly means that FIIs have been bullish on India

for much of that time. The problem is that such bullishness is often

driven by events outside the country, whether it be the performance

of other equity markets or developments in non-equity markets elsewhere

in the world. It is to be expected that FIIs would seek out the best

returns as well as hedge their investments by maintaining a diversified

geographical and market portfolio. The difficulty is that when they

make their portfolio adjustments, which may imply small shifts in favour

of or against a country like India, the effects it has on host markets

are substantial. Those effects can then trigger a speculative spiral

for the reasons discussed above, resulting in destabilising tendencies.

Thus the end of the bull run in January was seen to be the a result

of a slowing of FII investments, partly triggered by expectations of

an interest rate rise in the US.

These aspects of the market are of significance because financial liberalisation

has meant that developments in equity markets can have major repercussions

elsewhere in the system. With banks allowed to play a greater role in

equity markets, any slump in those markets can affect the functioning

of parts of the banking system. We only need to recall that the forced

closure (through merger with Punjab National Bank) of the Nedungadi

Bank was the result of the losses it suffered because of over exposure

in the stock market,

On the other hand if FII investments constitute a large share of the

equity capital of a financial entity, as seems to the case with HDFC,

an FII pull-out, even if driven by development outside the country can

have significant implications for the financial health of what is an

important institution in the financial sector of this country.

Similarly, if any set of developments encourages an unusually high outflow

of FII capital from the market, it can impact adversely on the value

of the rupee and set of speculation in the currency that can in special

circumstances result in a currency crisis. There are now too many instances

of such effects worldwide for it be dismissed on the ground that India's

reserves are adequate to manage the situation.

Thus, the volatility being displayed by India's equity markets warrant

returning to a set of questions that have been bypassed in the course

of neoliberal reform in India. The most important of those questions

is whether India needs FII investment at all. With the current account

of the balance of payments recording a surplus in recent years, thanks

to large inflows on account of non-resident remittances and earnings

from exports of software and IT-enabled services, we don't need those

FII flows to finance foreign exchange expenditures. Neither does such

capital help finance new investment, focussed as it is on secondary

market trading of pre-existing equity. The poor showing of the markets

on the IPO front in most years during the 1990s is adequate confirmation

of this. And finally, we do not need to shore up the Sensex, since such

indices are inevitably volatile and merely help create and destroy paper

wealth and generate, in the process, inexplicable bouts of euphoria

and anguish in the financial press.

In the circumstances, the best option for the policy maker is to find

ways of reducing substantially the net flows of FII investments into

India's markets. This would help focus attention on the creation of

real wealth as well as remove barriers to the creation of such wealth,

such as the constant pressure to provide tax concessions that erode

the tax base and the persisting obsession with curtailing fiscal deficits,

both of which are driven by dependence on finance capital.

©

MACROSCAN 2005