Themes > Features

6.02.2007

Women Workers in Urban India

In

the era of globalisation, it has become commonplace to argue that trade

openness in particular generates processes that encourage the increased

employment of women, particularly in export-oriented activities. In

addition, development in general and higher per capita incomes are supposed

to lead to more employment in services and shifts from unpaid household

work to paid work, which also involve more paid jobs for women workers.

Data

from the recent large sample employment survey of the NSSO would appear

to provide confirmation of this perception. Work participation rates

of women workers have increased in 2004-05, not only in comparison with

1999-2000 when they had fallen sharply, but also in comparison to a

decade earlier. However, this process needs to be considered in more

detail to see whether it is indeed the positive process outlined above.

Since this is meant to be much more marked in urban areas, this article

is concerned with changes in employment patterns of urban women workers

in India.

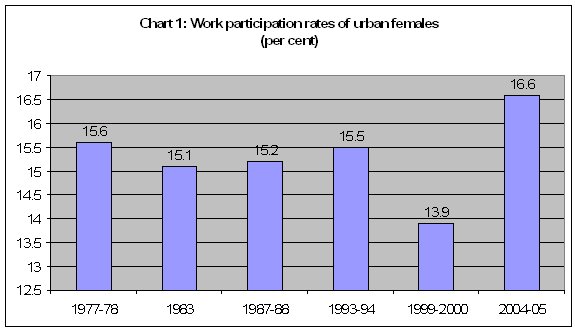

As Chart 1 shows, work participation rates have indeed increased and

in 2004-05 were at the highest rate of the past 25 years. (The year

1999-2000 now appears to be a significant outlier, and other problems

with that data suggest that the long terms trends are confirmed by the

most recent data.) Of course, these work participation rates are still

low by international standards, and reflect substantial variation across

states, with southern states showing generally higher rates.

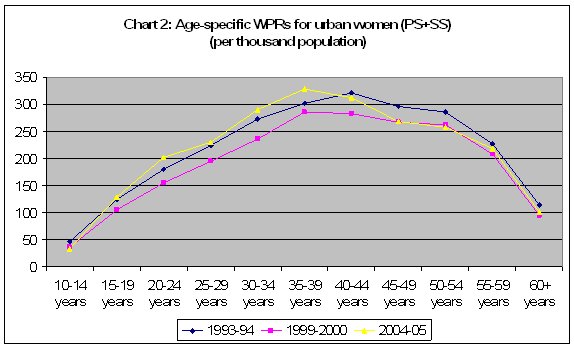

Chart 2 shows how the age specific work participation rates for urban women have changed over the past decade. There is a general tendency for women to enter into paid work at younger ages than previously - participation rates among younger urban women increased by about 2 percentage points compared to 1993-94 and 5 percentage points compared to 1999-2000. And the peak work participation rate for urban women has shifted from the age group 40-44 years in 1993-94 to 35-39 years in 2004-05.

So what type of employment do urban women workers find? Table 1 shows that there has been an overall decline in casual employment and a general increase in regular work and self-employment. The shift is especially marked in the case of principal activity, with more than 42 per cent of urban women workers now reporting themselves as having a regular job. When subsidiary activities are included, self-employment assumes greater significance, with nearly 48 per cent reporting as self-employed.

Table

1: Type of employment of usually employed urban women |

||||||

Principal

Status only |

Principal

+ Subsidiary Status |

|||||

Self-employed |

Regular |

Casual |

Self-employed |

Regular |

Casual |

|

| 1983 |

37.3 |

31.8 |

30.9 |

45.8 |

25.8 |

28.4 |

| 1987-88 |

39.3 |

34.2 |

26.5 |

47.1 |

27.5 |

25.4 |

| 1993-94 |

37.2 |

35.5 |

27.3 |

45.8 |

28.4 |

25.8 |

| 1999-2000 |

38.4 |

38.5 |

23.1 |

45.3 |

33.3 |

21.4 |

| 2004-05 |

40.4 |

42.2 |

17.4 |

47.7 |

35.6 |

16.7 |

This

is certainly a phenomenon to be welcomed, especially if it does indeed

indicate a shift to more productive and better remunerated activities

than are to be found with casual contracts. However, this needs to be

confirmed with evidence on the specific activities that are engaged

in and the trends in wages.

Table 2 provides the evidence on the broad sectoral classification of

work of urban women. Predictably, agriculture shows a substantial decline

over time. However, elsewhere there are surprises. The share of manufacturing

has increased slightly, but at around 28 per cent it is not much higher

than the proportion achieved in 1987-88, that is well before any export-led

manufacturing boom was in evidence. So the overall proportion of women

in manufacturing employment in urban India does not support the notion

of a big increase in female employment consequent upon greater export

orientation of production.

Table

2: Main sectors of employment of urban women workers (Principal plus subsidiary status) |

|||||

Per

cent of usually employed urban women |

|||||

| 1983 |

1987-88 |

1993-94 |

1999-2000 |

2004-05 |

|

| Agriculture | 31 |

29.4 |

24.7 |

17.7 |

18.1 |

| Manufacturing | 26.7 |

27 |

24.1 |

24 |

28.2 |

| Construction | 3.1 |

3.7 |

4.1 |

4.8 |

3.8 |

| Trade, hotels & restaurants | 9.5 |

9.8 |

10 |

16.9 |

12.2 |

| Transport & communications | 1.5 |

0.9 |

1.3 |

1.8 |

1.4 |

| Other services | 26.6 |

27.8 |

35 |

34.2 |

35.9 |

Even

trade, hotels and restaurants, which are activities traditionally considered

to attract a lot of women workers, do not show much increase, and the

share of these has even declined compared to 1999-2000. The clear increase,

even if not very dramatic, is for other services, which is a catch-all

for a wide range of both public and private services, as well as both

high value added high-remuneration jobs and very low productivity low

paying survival activities.

It is worth considering the patterns in manufacturing employment in

more detail, particularly because the work of women can be easily misclassified

in the available data. In particular, the usual status definition which

includes both principal and subsidiary status activities can be a source

of confusion. It is possible that women are classified as ''usually

working'' when in fact it may reflect underemployment or engagement

in a subsidiary activity only. Indeed, there can be substantial variation

in the type of employment contract depending upon whether the activity

is a ''principal'' one or a ''subsidiary'' one.

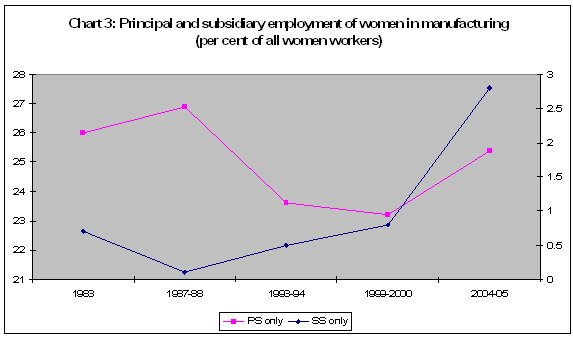

Chart 3 makes this very evident in the case of manufacturing employment.

In terms of principal status, the share of women workers in manufacturing

has fluctuated sharply between 23 and 27 per cent, and there is no evidence

of a clear trend. However, the share of women working in manufacturing

in a subsidiary capacity (that is, not as the perceived principal activity

of the women concerned) has been increasing continuously since 1987-88,

and now accounts for as much as nearly 3 per cent of all urban women

workers. This in turn is now as much as 11 per cent of all women employed

in manufacturing - surely not a small proportion.

What

could explain this very substantial difference once subsidiary activities

are included? One important factor may be the increase in putting out

home-based or other work as part of a subcontracting system for export

and domestic manufacturing. Such work does not get incorporated in the

employment statistics which are based on employers' records, and this

may explain the paradox that even while women's share of employment

in manufacturing has not increased much, the dependence of the sector

- and especially of export-oriented manufacturing - on the productive

contribution of women may well have increased.

This suggests that the direct and formally recognised involvement of

women may have stagnated even in the period of the relative higher growth

of exports over the last decade. However, home-based subcontracting

activities, or work in very small units that do not even constitute

manufactories, often on piece rate basis and usually very poorly paid

and without any known non-wage benefits, may to some extent have substituted

for the more standard form of regular employment on a regular wage or

salary basis.

Table 3 provides some data on the actual numbers of women employed in

various activities in urban India, based on applying the NSSO work participation

rates to the Census estimates and projections of urban population. The

results are quite startling, especially in the context of the much-trumpeted

high output growth rates which are widely felt to have predominantly

affected urban India in positive ways.

Thus, it turns out that relatively few sectors now account for two-thirds

of all women workers, whether in principal or subsidiary status. Some

of them are indeed the dynamic export-oriented activities. Thus, the

number of women employed in textiles has nearly doubled and those in

apparel and garments have increased by more than two and a half times.

There has also been significant increase in employment in the leather

goods sector.

In the service sectors, there has been very little increase in female

employment in public administration, reflecting the overall constraints

on such employment, although employment in education (mainly with private

employers) has shown a large increase. However, the biggest single increase

after apparel - and the category of work that is now the single largest

employer for urban India women - has been among those employed in private

households. In other words, women working as domestic servants now number

more than 3 million, and account for more than 12 per cent of all women

workers in urban India.

Table

3: Main sectors of employment of urban women workers |

|||

1999-2000 |

2004-05 |

per

cent change |

|

| Food products & beverages |

400,441 |

418,593 |

4.5 |

| Tobacco products |

891,891 |

911,055 |

2.1 |

| Textiles |

1,037,506 |

1,920,602 |

85.1 |

| Apparel |

436,845 |

1,600,502 |

266.4 |

| Leather & leather goods |

72,807 |

196,985 |

170.6 |

| Chemicals & chemical products |

345,835 |

467,839 |

35.3 |

| Construction |

873,690 |

935,678 |

7.1 |

| Retail trade |

2,493,656 |

2,117,587 |

-15.1 |

| Hotels & restaurants |

400,441 |

615,578 |

53.7 |

| Finance |

273,028 |

418,593 |

53.3 |

| Pub admin, defence & social security |

709,873 |

763,316 |

7.5 |

| Education |

2,056,811 |

2,856,280 |

38.9 |

| Employed in private households |

946,497 |

3,053,265 |

222.6 |

| Total | 10,939,321

|

16,275,871 |

|

| per cent of all workers | 60

|

66 |

|

| All urban women workers | 18,201,866

|

24,623,103 |

|

It

is indeed disturbing to see that the greatest labour market dynamism

has been evident in the realm of domestic service. This is well known

to be poorly paid and often under harsh conditions - and certainly,

it cannot be seen as a positive sign of a vibrant dynamic economy undergoing

positive structural transformation.

The newer activities that are much cited - such as IT and finance -

continue to absorb only a tiny proportion of urban women workers, which

is why they have not been included in this table. Thus, women workers

in all IT related activities - that is, computer hardware and software

as well as IT-enabled services - account for only 0.3 per cent of the

urban women workers in this large sample, amounting to an estimated

total of 74,000 workers at most.

Similarly, women workers in all financial activities - that is formal

financial intermediation through banks and other institutions, life

insurance and pension activities and other auxiliary financial activities

- added up to only 1.4 per cent of the women workers in urban India.

So there is clearly a long way to go before the newer sectors - or even

traditional but more dynamic exporting sectors such as textiles and

garments - can make a dent in transforming labour conditions for urban

Indian women.

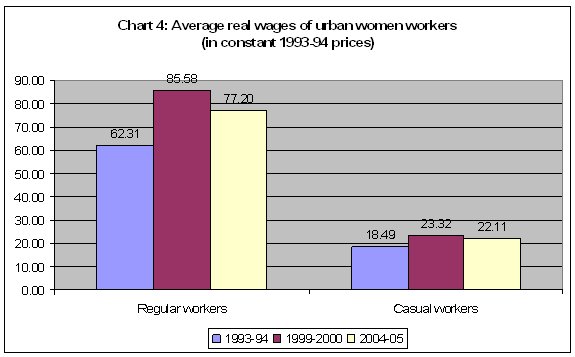

This is probably why the evidence on real wage trends of urban women

is so disappointing. Chart 4 indicates that average real wages have

fallen between 1999-2000 and 2004-05 for both regular and casual women

workers, and have hardly increased much even in relation to more than

a decade earlier. For an economy that boasts of one of the highest GDP

growth rates in the world over this period, this is certainly an indictment.

©

MACROSCAN 2007