Themes > Features

15.02.2010

The Crisis and Employment in Asia

Ever

since the global financial and economic crisis broke, the International

Labour Organisation (ILO) has been regularly tracking its impact on

the level and quality of employment. In January 2009, the ILO (International

Labour Office 2009) indicated that, under alternate scenarios, global

unemployment could increase by between 18 million or 51 million people

worldwide from 2007 to 2009. By June 2009 the range for 2009 had shifted

upwards, to an increase of between 29 million and 59 million unemployed

over the period from 2007 to 2009.

The most recent estimates put out by the ILO suggest that this range

was broadly indicative, though the outcome appears to be closer to its

lower bound. In its January 2010 update, the ILO estimates global unemployment

at 212 million in 2009, or around 34 million above its 2007 level, with

most of the increase having occurred during 2009. In sum, the impact

of the fiscal stimuli delivered by many governments does not seem to

be as yet adequate to stall, let alone reverse the employment decline

resulting from the crisis. This increase in unemployment was unevenly

distributed, with Developed Economies and the European Union, Central

and South-Eastern Europe and CIS countries, and Latin America and the

Caribbean accounting for more than two-thirds of the increase in the

number of unemployed during 2009. In other words, South-East Asia and

the Pacific, East Asia and South Asia were much less affected.

It needs to be noted, however, that in most countries unemployment figures

do not tell the whole story. With social protection inadequate or lacking

altogether, those in the working age groups need to take on some form

of employment or starve. Hence, recorded unemployment rates tend to

be low. Thus, what is more telling is to look at a combination of the

trends in aggregate employment and more importantly in the quality of

that employment. According to the ILO, in 2009, employment growth became

negative in two regions (Developed Economies and the European Union

and Central and South-Eastern Europe and CIS countries) while employment

growth in Latin America and the Caribbean dropped to near zero. In all

regions except South-East Asia and the Pacific and the Middle East,

employment growth declined below the average annual growth in the first

half of the decade.

This is surprising, since it is to be expected that countries that are

more dependent on foreign trade and investment flows, such as those

in South-East Asia, would have been more affected by the crisis. The

region experienced the sharpest reductions in economic growth because

of the crisis. Economic growth in the region as a whole is expected

to fall to 0.5 per cent in 2009, down from 4.4 per cent in 2008 and

from an average annual rate of more than 6 per cent prior to the crisis.

The countries that have experienced the sharpest declines in growth

in 2009 are Cambodia (where growth fell to -2.7 per cent from 6.7 per

cent in 2008 and more than 10 per cent in the years leading up to the

crisis), Malaysia (-3.6 per cent growth in 2009), Thailand (-3.5 per

cent growth in 2009), Singapore (-3.3 per cent) and Fiji (-2.5 per cent).

According to the ILO, the presence of a major economy like Indonesia,

which has a large domestic market and is less dependent on trade has

buffered the region and unemployment in the ILO scenarios is projected

to increase by a moderate 1.2 million (with an upper bound of 2 million

and a lower bound of 0.5 per cent).

Overall, the presence of countries where growth is largely based on

the domestic market is seen as positive from the point of view of the

intensity of the downturn and its effects on employment. In South Asia,

the fact that growth in the larger economies like India and Pakistan

is based more on the domestic market than exports has blunted the impact

of the crisis on growth and employment.

That having been said there are four features of labour market trends

in the Asia-Pacific region that need to be noted. First, there are many

small disadvantaged countries, including the small landlocked and island

economies in the region that have no domestic market to speak of and

therefore are perforce (and not just by strategy), heavily dependent

on exports. Second, three decades of liberalisation have meant that

all regions and countries in the Asia-Pacific have increased their dependence

on exports, even if to differing degrees. Third, in almost all countries

there are at least a few sectors (whether they be primary products,

manufacturing or informational technology services) in each country

where export dependence is high. And, fourth there are routes other

than an export slowdown – domestic demand decline, reduced credit access,

etc. – through which the global downturn transmits itself to developing

countries, affecting employment even in sectors and industries dependent

on domestic markets.

However,

underlying the better performance of this region in terms of aggregate

employment are certain disconcerting trends. This comes through from

an examination of countries in South-East Asia and the Pacific for which

more recent data is available from labour force surveys. Given the fact

that unemployment is the exception for individuals in countries without

adequate or any social protection, the impact of the reduction in growth

is felt more in terms of deterioration in the quality of employment

rather than a decline in its volume. The ILO defines workers in vulnerable

employment as consisting of own-account workers and contributing family

workers, who are less likely to have formal work arrangements, and are

therefore more likely to lack elements associated with decent employment

such as adequate social security and recourse to effective social dialogue

mechanisms. As a result, vulnerable employment is often characterized

by inadequate earnings, low productivity and difficult conditions of

work that undermine workers' fundamental rights.

In some countries in South-East Asia, the impact of crisis has been

an increase in vulnerable employment rather than in recorded unemployment.

With job losses in the export sector the proportion of workers in vulnerable

employment in export dependent countries has tended to increase. According

to the ILO: ''Both the proportion and the number of workers in vulnerable

employment in South-East Asia and the Pacific have risen since 2008,

with the middle scenario providing a projected increase of almost 5

million. This trend is to be expected, as many workers who have lost

their job in export-oriented manufacturing cannot afford to join the

ranks of the unemployed and instead will take up employment in the informal

sector, perhaps working in agricultural activities or in informal services,

such as street vending.''

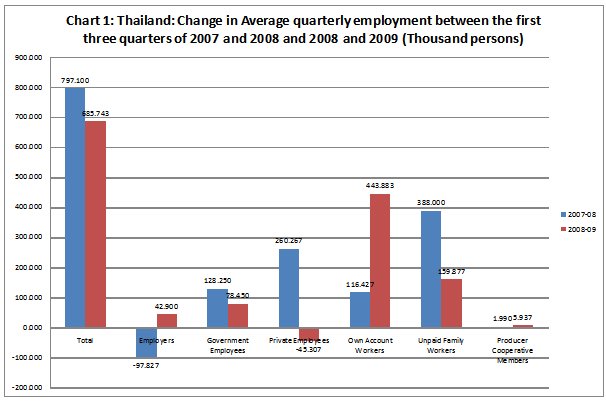

Consider, for example, a country like Thailand, for which employment

figures under different status categories are available from the National

Statistical Office till as recently as September 2009. The figures show

that if we take average quarterly figures for the first three quarters

of 2007, 2008 and 2009, the increase in overall employment fell from

around 797,000 between 2007 and 2008 to 686,000 between 2008 and 2009.

But this was accompanied by significant changes in the pattern of employment.

The number of private employees, which grew by 260,000 between 2007

and 2008, declined by 45,000 between 2008 and 2009 because of the impact

of the crisis on the country's export industries. Over the same periods

the increase in the number of own-account workers rose from 116,000

to 444,000 and those in vulnerable employment as per the ILO's definition

rose from 504,000 to 604,000. Unable to obtain employment in the export

industries that had hitherto sustained them, workers were seeking any

form of employment in order to survive.

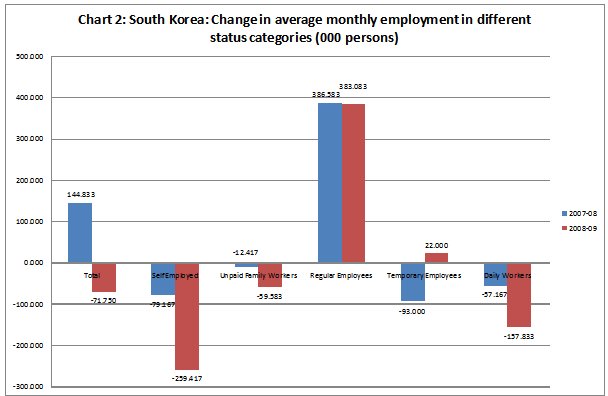

However, the experience differs across countries. In South Korea, average

monthly employment, which rose by 144,833 between 2007 and 2008, fell

by 71,750 between 2008 and 2009. What is remarkable was the sharp rise

in the number of jobs lost in the self-employed (from 79,000 to 259,000),

unpaid family worker (12,400 to 60,000) and daily worker (57,000 to

158,000) categories. That is, there was a huge decline in vulnerable

employment. On the other hand, the absolute increase in the monthly

average number of regular employees remained more or less constant in

the 380,000 range. One explanation for this very different experience

could be that the government's efforts at a stimulus kept regular jobs

rising, but the impact of the crisis damaged sectors relying on self-employed

or irregularly employed workers for their survival.

Finally, there are specific groups that have been affected particularly

adversely. Besides marginalised or disadvantaged sections, the impact

of the crisis was significant in the case of women and youth. Women

were affected not merely because of the all-prevalent gender discrimination,

but also because in many countries there has been some degree of feminisation

of export employment, especially in the case of low value added, labour

intensive processing. And with unemployment and underemployment on the

rise, new entrants into the labour market among the youth are bound

to find it difficult to find themselves decent work.

These trends in Asia are of significance because at the time when the

crisis was just beginning to unfold, optimists pointed to Asia as the

shock absorber that would buffer the global downturn. A decoupled Asia,

it was argued, would through its own growth and the demands that it

would make on the world's output ensure that the financial crisis that

was largely a phenomenon restricted to the developed countries would

not have as damaging an effect on global growth as the pessimists, then

in a minority, were predicting. That prognosis has turned out to be

only partially, and in some cases marginally, correct.

What is more the recovery has been accompanied by a return of inflation

to commodity markets, with increases in food and oil prices. This is

seen as making the current recovery driven by large-scale public spending

a source of danger inasmuch as it can once again trigger commodity price

buoyancy. And even as the world hesitantly looks forward to recovery

the fear that commodity price inflation would threaten the process of

adjustment is on the increase.

This fear has created a situation where there is uncertainty about the

continued use of the most obvious tool for combating a recession, viz.

substantially increased government spending to stimulate demand in the

domestic market. Since the adoption of programmes of economic liberalisation

(which included customs duty reductions, indirect tax rationalisation

and direct tax concessions), countries have been faced with a reduction

in their sources of revenue and in the volume of taxes they garner from

traditional sources of revenue. Hence, enhanced expenditures are often

financed with larger deficits, which go contrary to the tenets of fiscal

reform. On the grounds that such deficit-financed spending would trigger

inflation, especially in the case of food items, it has been argued

that governments, especially governments in developing countries should

desist from relying excessively on deficit-financed government stimuli

to combat recessions and rising unemployment. This could stall the incipient

recovery in output and employment in these countries.

©

MACROSCAN 2010