Themes > Features

23.02.2010

Controlling Food Prices

As

usual when the Union Budget is presented, all eyes will be on the Finance

Minister and his speech will be thoroughly scanned for all the implications

on the economy. But this time, there is one particular reason why ordinary

citizens will be specially focussed on the Budget: the hope that the

Government is finally going to act decisively to contain food price

inflation.

It

is not surprising that questions of food security and the right to food

have become such urgent political and social issues in India today.

Rapid aggregate income growth over the past two decades has not addressed

the basic issue of ensuring the food security of the population. Instead,

nutrition indicators have stagnated and per capita calorie consumption

has actually declined, suggesting that the problem of hunger may have

got worse rather than better. So despite apparent material progress

in the last decade, India is one of the worst countries in the world

in terms of hunger among the population, and the number of hungry people

in India is reported by the UN to have increased between the early 1990s

and the mid-2000s.

These very depressing indicators were calculated even before the recent

rise in food prices in India, which is likely to have made matters much

worse. Indeed, the rise in food prices in the past two years has been

higher than any period since the mid-1970s, when such inflation sparked

widespread social unrest and political instability. What is especially

remarkable is that food prices have been rising even when the general

price index (for wholesale prices) has been almost flat; thus, when

the overall inflation rate was only around 1-2 per cent in the past

year, food prices increased by nearly 20 per cent!

Table 1 indicates the price increase in cities averaged across the major

regions, for rice, atta and sugar, which are among the most essential

food items in any household. It is evident that the price increase has

been so rapid as to be alarming especially over the past two years,

with rice prices increasing by nearly half in Northern cities and more

than half in Southern cities. Atta prices have, on average, increased

by around one-fifth from their level of two years ago. The most shocking

increase has been in sugar prices, which have more than doubled across

the country. Other food items, ranging from pulses and dal to milk and

vegetables, have also shown dramatic increase especially in the past

year.

Table

1: Table 1: Retail prices in major cities/towns, by zone. |

|||||||

Average

retail price on 27.01.10 (in Rupees) |

Increase

over 1 year (per cent) |

Increase

over two years (per cent) |

|||||

|

Rice

|

|||||||

North

Zone |

19.92 |

11.94 |

48.45

|

||||

|

West Zone |

19.33

|

9.78 |

29.37 |

||||

|

East Zone |

16.19 |

10.31 |

16.30

|

||||

|

South Zone |

22.25 |

32.84

|

58.93

|

||||

|

Atta

|

|||||||

North

Zone |

17.00 |

24.90 |

24.90 |

||||

|

West Zone |

17.17

|

15.73

|

21.85 |

||||

|

East Zone |

17.50 |

19.32

|

22.09

|

||||

|

South Zone |

20.38 |

5.16

|

13.19

|

||||

|

Sugar

|

|||||||

North

Zone |

36.17 |

64.08 |

156.05

|

||||

|

West Zone |

34.61

|

66.58

|

122.50 |

||||

|

East Zone |

37.88 |

74.64

|

118.77

|

||||

|

South Zone |

32.19 |

61.44

|

109.35

|

||||

| Source: Ministry of Food and Civil Supplies, Food Price Monitoring System, 12 February 2010. | |||||||

There are many reasons why food prices have risen at such a rapid rate,

and all of them point to major failures of state policy. Domestic food

production has been adversely affected by neoliberal economic policies

that have opened up trade and exposed farmers to volatile international

prices, even as internal support systems have been dismantled and input

prices have been rising continuously. Inadequate agricultural research,

poor extension services, overuse of ground water, and incentives for

unsuitable cropping patterns have caused degeneration of soil quality

and reduced the productivity of land and other inputs. Women farmers,

who constitute a large (and growing) proportion of those tilling the

land, have been deprived of many of the rights of cultivators, ranging

from land titles to access to institutional credit, knowledge and inputs,

and this too has affected the productivity and viability of cultivation.

But

in addition to production, poor distribution, growing concentration

in the market and inadequate public involvement have all been crucial

in allowing food prices to rise in this appalling manner. Successive

governments at the Centre have been reducing the scope of the public

food distribution system, and even now, in the face of the massive increase

in prices, the Central government is delaying the allocation of food

grain for the Above Poverty Line population to the states. This has

prevented the public system from becoming a viable alternative for consumers

and preventing private speculation and hoarding. In addition, allowing

corporate (both domestic and foreign companies) to enter the market

for grains and other food items has led to some increase in concentration

of distribution. This has not been adequately studied, but it has many

adverse implications, including the fact that farmers will benefit less

from period of high prices even as consumers suffer, because the benefit

will be garnered by middlemen.

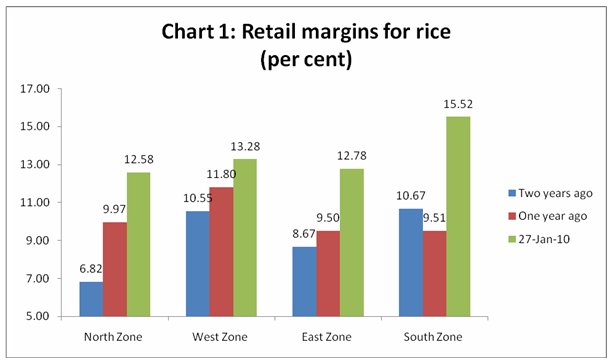

Thus it has been found that the gap between farm gate and wholesale

prices is widening. A similar story emerges in the gap between wholesale

and retail prices, as evident in the charts. In rice, the gap between

average wholesale and retail prices widened considerably - even doubled

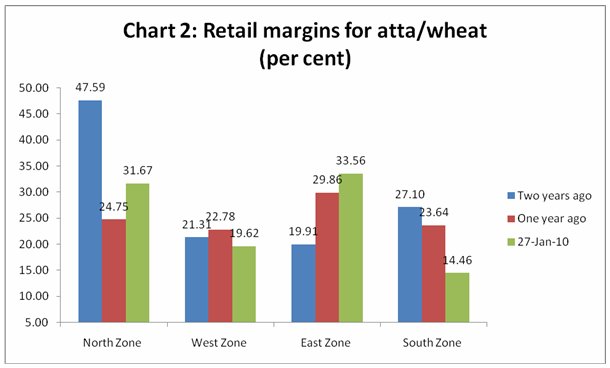

- across the four major zones of the country, as shown in Chart 1. In

wheat (Chart 2), the pattern is more uneven but the retail margins are

very large indeed, as expressed by the difference between the wholesale

price of wheat and the retail price of atta (which is the most basic

first stage of processing).

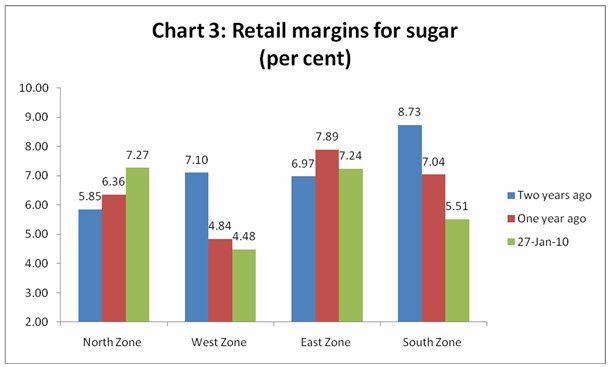

Sugar is slightly more complicated, as marketing margins appear to show

different trends in different regions and also tend to be significantly

lower than the other major crops. The dramatic increase in sugar prices

is more a reflection of massive policy errors over the past two years,

in terms of supply and domestic price management, and exports and imports.

So

what exactly is happening? It appears that there are forces that are

allowing marketing margins - at both wholesale and retail levels - to

increase. This means that the direct producers, the farmers, do not

get the benefit of the rising prices which consumers in both rural and

urabn areas are forced to pay. The factors behind these increasing retail

margins needs to be studied in much more detail. The role of expectations,

especially in the context of a poor monsoon that was bound to (and did)

affect the kharif harvest adversely, should not be underplayed. But

that refers only to the most recent period of rising prices, whereas

this process has been marked for at least two years now.

In

addition to this, there is also initial evidence that there has been

a process of concentration of crop distribution, as more and more corporate

entities get involved in this activity. Such companies are both national

and multinational. On the basis of international experience, their involvement

in food distribution initially tends to bring down marketing margins

and then leads to their increase as concentration grows. This may have

been the case in certain Indian markets, but this is an area that clearly

merits further examination.

Many people have argued, convincingly, that increased and more stable

food production is the key to food security in the country. This is

certainly true, and it calls for concerted public action for agriculture,

on the basis of many recommendations that have already been made by

the Farmers' Commission and others. But another very important element

cannot be ignored: food distribution. Here too, the recent trends make

it evident that an efficiently functioning and widespread public system

for distributing essential food items is important to prevent retail

margins from rising.

So one major element of the Finance Minister's speech that will certainly

be noticed is the outlay he proposes for the Food Corporation of India.

The UPA government has already pledged to enact a Food Security Bill,

but that needs to be universal in coverage (rather than confined to

Below Poverty Line population) and provide enough volumes to meet minimum

requirements. A universal system of public food distribution provides

economies of scale; it reduces the transaction costs and administrative

hassles involved in ascertaining the target group and making sure it

reaches them; it allows for better public provision because even the

better off groups with more political voice have a stake in making sure

it works well; and it generates greater stability in government plans

for ensuring food production and procurement.

But even before such a law is passed, it is clear that emergency measures

are required to strengthen public food distribution, in addition to

medium-term policies to improve domestic food supply. A properly funded,

efficiently functioning and accountable system of public delivery of

food items through a network of fair price shops and co-operatives is

the best and most cost-effective way of limiting increases in food prices

and ensuring that every citizen has access to enough food.

In a context in which the inflation is concentrated on food prices,

measures like raising the interest rate are counterproductive because

they affect all producers without striking at the heart of the problem.

Instead, if he is serious about curtailing food inflation, the Finance

Minister must provide substantially more funds to enable a proper and

effective public food distribution system.

©

MACROSCAN 2010