Themes > Features

03.02.2011

Food Prices and Distribution Margins in India

The

dramatic increase in food inflation over the past two years has been

associated with several surprises. One major surprise has been how the

top economic policy makers in the country have responded to it. The

initial response was one of apparent disbelief, followed very quickly

by the frequently repeated but thus far unsubstantiated conviction that

prices would come down very soon.

Then

this massive increase in the price of essential commodities was welcomed,

even by those who should know better, as being a sign of greater material

prosperity in the country and the success of ''pro-poor'' schemes of

the government, reflected in increased demand for food. Could it be

that the economists who are running the country apparently believed

that food demand should not increase much even in periods of significant

aggregate income growth, and among a population that has the some of

the worst nutrition indicators in the world? Is that why they did not

see any need to work towards increased supply of food and have been

so surprised by even a slight increase in demand?

As it happens, in fact demand for food has been growing much more slowly

than could be anticipated by both income and population growth. Much

of that has to do with the distribution of that growth, which has disproportionately

denied benefits to the poor who would naturally consume more food. But

even so, the fact that it is really the conditions of supply – reflecting

the continuing policy neglect of agriculture as well as the nature of

distribution and the pressures on the market from speculative activity

– that have driven food prices up.

This recognition may be why the official arguments have changed somewhat

recently. Most recently the officially stated position has been to blame

inadequate existing distribution chains – focusing on their inefficiency,

rather than any speculative pressures that could also affect supply.

This has become the most popular interpretation of the ongoing food

crisis in the corridors of power and their stenographers in the financial

press. This has consequently led to the demand that modern corporate

retail chains (ideally with FDI) be brought in to manage food distribution.

As a result, there are now those who have argued that the only solution

to the problem of high food prices is to bring in FDI in retail! It

is argued that this will reduce wastage in storage and costs of transport

of food items, cut out intermediaries in distribution and provide food

more effectively to consumers at lower prices.

Of course this argument is rather foolish, at several levels. First

of all, if the traditional supply chains in food items are so faulty

and deficient, why did they not create such massive food price spikes

earlier? Why was food inflation relatively low in the period until 2006,

despite equally rapid GDP growth and the same system of distribution

that is being faulted?

Secondly, if the problem is inadequate infrastructure, including cold

storage facilities and quicker distribution networks from farm to market,

what stopped the government from more proactive intervention to ensure

better cold storage and other facilities through various incentives

and promotion of more farmers' co-operatives? To announce such measures

only now, as a weak response to a period of raging food inflation is

futile, because obviously such measures operate only with a significant

time lag. This is all the more so because such proposals are explicitly

mentioned in the Farmers' Commission Report, which has been lying with

the government for half a decade now. The idea that cold storage and

other facilities can only be developed by large corporates once they

get directly involved in retail food distribution is ridiculous at best.

Thirdly, this entire argument completely ignores the critical role that

can be played by a public distribution system in moderating such food

price spikes and dampening inflationary expectations and tendencies

of hoarding. Instead of accepting the failure of the government to use

this system effectively so far, the tendency is to throw up hands and

declare that only the large private sector can save us, even though

international evidence indicates that corporate monopoly in food trade

typically increases distribution margins rather than reducing them.

Unfortunately, though, we are forced to take such arguments seriously

because they are being repeated ad nauseum by the media and pushed into

government policies by corporate lobbies. So let us consider what the

recent evidence on distribution margins indicates.

In fact, there is significant reason to believe that the margins between

wholesale and retail prices of many important food items have increased

in the recent period. (See MacroScan, Businessline, 23 February 2010)

The point is that this has been happening in a period of increased corporate

involvement in food distribution and food retail. The share of corporate

retail in food distribution in the country as a whole is estimated to

have tripled in the past four years, and has grown even faster in major

metros and other large cities. And this is also the period when retail

food prices have shown the greatest increase!

The other point that emerges from a comparison of retails margins across

major towns and cities is that such margins are lowest in the states

(like Tamil Nadu and Kerala) where there is an extensive, well-developed

and reasonably efficient system of public distribution that provides

a range of food items on a near universal basis to the population. In

regions where such a public distribution system is weak or non-existent

(such as Utter Pradesh and Bihar) the margins tend to be much higher

and growing faster, even though corporate food retailing in such regions

has been expanding.

So to look at corporate retail as the solution to the current food price

increase is more than irresponsible. There is no question that the current

system of food procurement from farmers is inadequate, faulty and often

quite anti-farmer. There is much that needs to be reformed in the way

that market yards are organised and in the options available to farmers

to get their produce to market. There is a range of necessary and possible

interventions for this, most of which have been stated many times to

the government by various Commissions of its own. Yet thus far the UPA

government has done little about any of these, even in terms of working

with state governments to improve the situation, and instead seems to

think that simply allowing more corporate (and FDI) activity in retail

will allow it to wash its own hands of the matter.

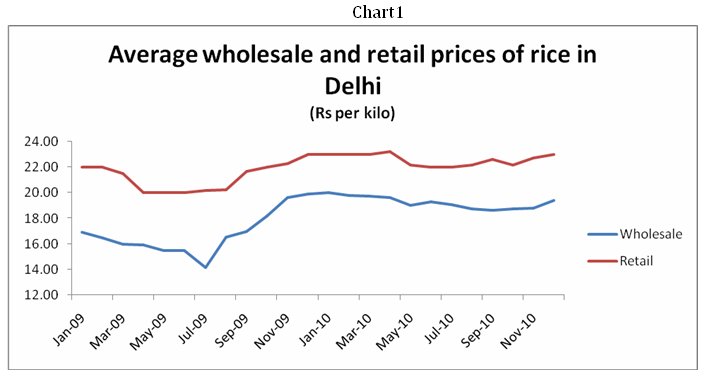

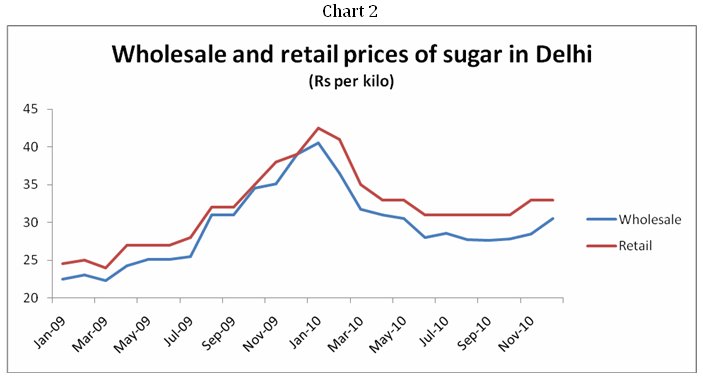

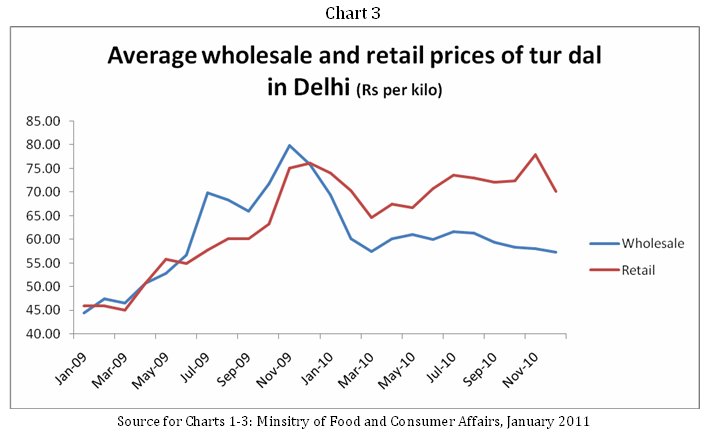

In this context, consider how retail margins have been behaving in the

very recent past, in just one location, the city of Delhi. Charts 1,

2 and 3 describe the price behaviour of three significant but relatively

less perishable food items: rice, sugar and tur dal.

It

is evident that the retail prices have generally been tracking the wholesale

prices in terms of direction of movement, but still there are some noteworthy

variations. On average, retail margins have increased for all these

commodities, and quite sharply for tur dal. This may be the result of

a number of features, and obviously requires more investigation. But

even so it is worth noting that Delhi is a city that has witnssed a

signfiicant increase in corporate food retail. And the role of inflationary

expectations in being able to influence retail price behaviour is obviously

much greater for larger players.

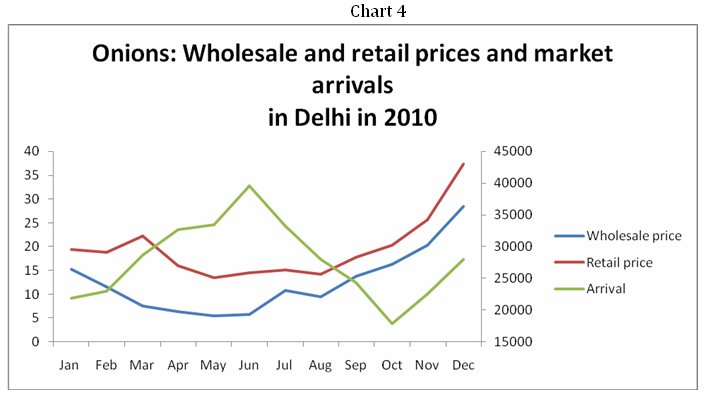

The food prices that have been most talked about of course are those

of onions. Onion prices are widely perceived to have great political

significance, especially in North India. Because onions like other vegetables

are highly perishable, supply conditions should play a major role in

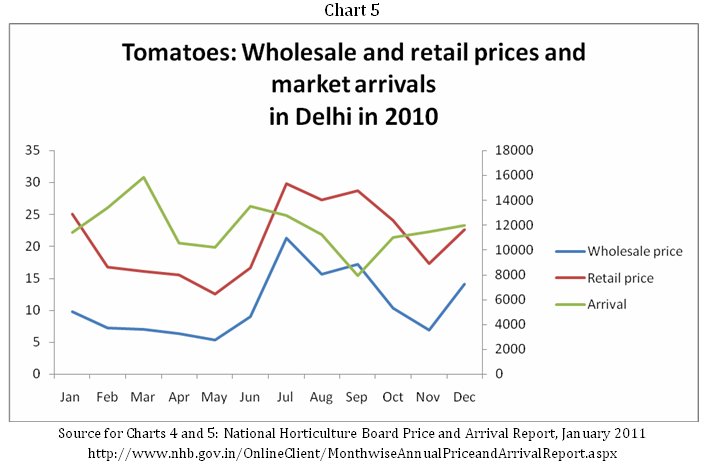

their price. Charts 4 and 5 describe the wholesale and retail prices,

and the total market arrivals of onions and tomatoes in the city of

Delhi.

The evidence is somewhat surprising. For much of the period of falling

market arrivals over the past year, onion prices were rather stable

and the retail margin actually shrank. Prices started rising sharply

only in October – and this is the period after which supply was actually

increasing quite sharply! In November and December, market arrivals

increased but prices continued to shoot up. Surely inflationary expectations

and hoarding must have played roles, along with speculative pressure,

and this was not sufficiently counteracted by public intervention through

its own food distribution network.

The case of tomato prices is similarly interesting. It is evident that

neither wholesale nor retail prices had much relation to market arrivals,

even for this extremely perishable commodity. But what the period of

higher prices has been associated with is a significant increase in

retail margins in October and November.

Dealing systematically with the problem of high food prices in a context

of a largely hungry population should normally be a priority issue for

any government. There are certainly crucial medium term policies that

reverse the longer run neglect of agriculture, that must be implemented.

The issue of rapidly rising cultivation costs that are making farming

unviable once again, needs to be addressed in a holistic way. The concerns

of storage, distribution and post-harvest technology also need to dealt

with. But in the short run, the problem cannot be avoided by talking

of astrologers and the inability of mere humans to predict the future.

Instead, creating a viable and effective public distribution system

that will counteract tendencies to price spikes in essential commodities

is an immediate requirement.

©

MACROSCAN 2011