It

began with the Reserve Bank of India's third quarter

2011-12 Review of Macroeconomic and Monetary Developments

released on January 23, 2012. Its assessment of the

situation in India's external sector noted that: ''Risk

aversion in the global financial markets has slackened

the pace of capital flows to India… If the pace of

FDI inflows does not pick up once again and FII equity

inflows revert to the decelerating trend, CAD (current

account deficit) may have to be largely financed through

debt creating flows in the coming quarters.'' It also

underlined the fact that signs of a recent revival

of FII inflows were largely on account of investment

in debt instruments. A few days later, RBI Governor

D. Subbarao, referring to the rise in debt flows,

publicly emphasised that India has ''a preference for

non-debt flows over debt flows'', and ''within non-debt

flows, more of FDI''.

Chart

1 >>

(Click to Enlarge)

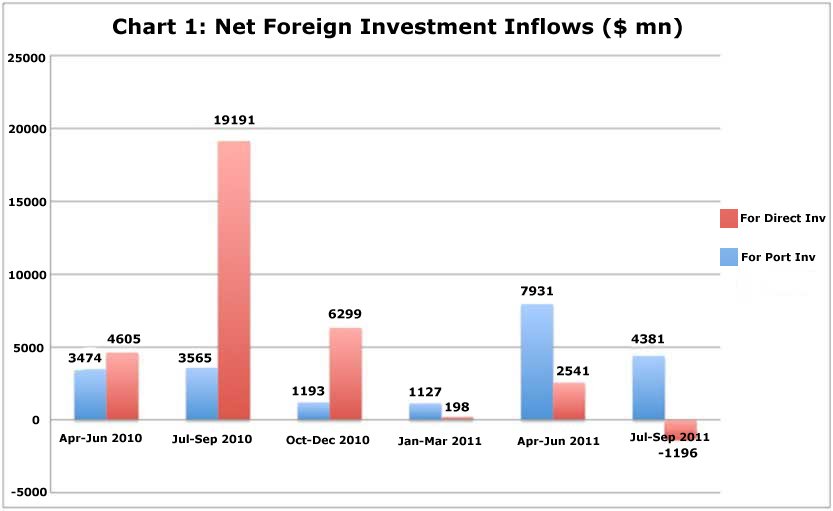

Along with the expression of such fears the government

has been liberalising foreign investment rules to

attract equity inflows in lieu of debt. The most recent

such policy allows individual investors to invest

in equity. The justification provided for these fears

and policies is the evidence that investments in Indian

equity have decelerated during the first half of fiscal

year 2011-12 when compared to the recent past (Chart

1). In particular, there has been a collapse of foreign

portfolio investment flows, leading to an overall

fall in external investment in equity.

The RBI has released some preliminary figures for

the third quarter of 2011-12 (Table 1). These figures

also point to a decline in monthly average inflows

of foreign equity investments during September to

November in the case of direct investment and September

to December 2011 in the case of portfolio investments.

But the decline is by no means dramatic.

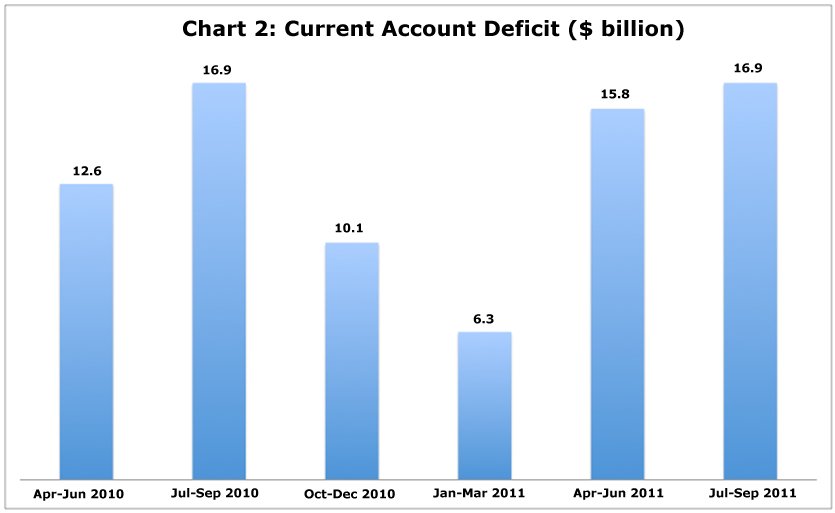

These changes have been occurring at a time when the

external current account deficit, which had fallen

in the second half of fiscal 2010-11, has risen significantly

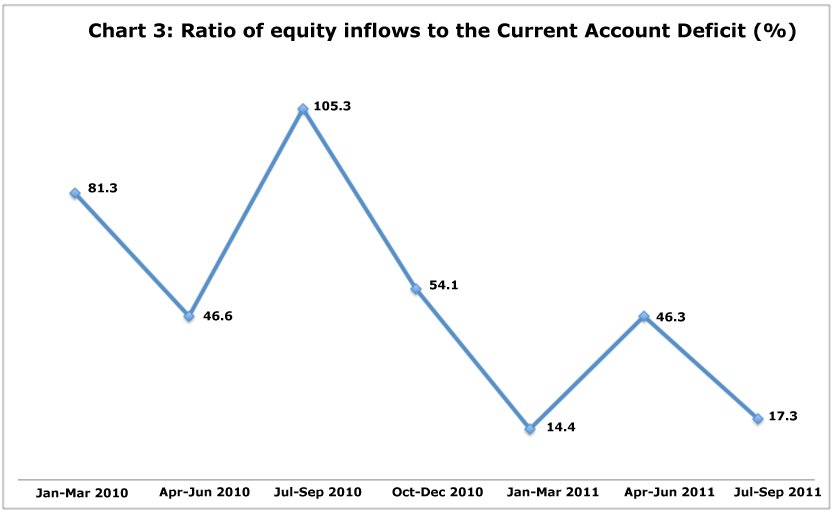

(Chart 2). As a result, a rising share of a rising

deficit is being financed with non-equity flows. The

ratio of direct and equity investment flows to the

current account deficit in India appears to have shifted

downwards over a relatively short period of time (Chart

3). The conclusion arrived at is that India has had

to increase its reliance on debt creating flows to

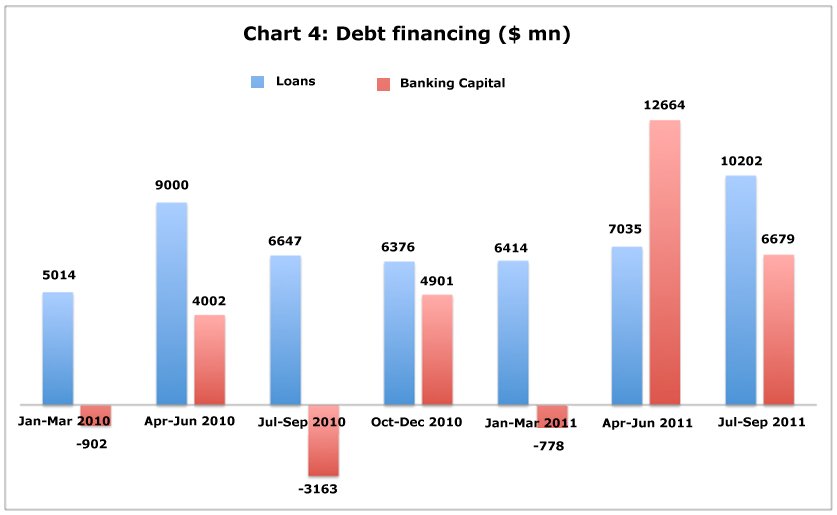

finance its current account deficit. Supporting that

is the evidence that inflows in the form of loans

and banking capital have together risen quite sharply

during the first two quarters of this fiscal year

(Chart 4).

Table

1: Capital Flows during 2011-12 ($ bn) |

|

2011-12 |

2011-12

|

|

(Apr.-Aug.) |

(Sep.-Dec.)

|

|

(Monthly

Average)

|

FDI

to India* |

4.9 |

3.2 |

FDI

by India |

1 |

0.8 |

FIIs

(net) |

0.4 |

0.1 |

ADRs/GDRs

|

0.1 |

0.1

|

ECB

Inflows (net) |

1.3 |

0.6 |

NRI

Deposits (net) |

0.5 |

1.2

|

* : April-November.

|

Table 1 >>

(Click to Enlarge)

Though fully collated figures for the period since

September 2011 are yet to be released, there are reports

that these tendencies have only intensified more recently.

According to one report (Indian Express, January 30,

2012), during calendar year 2011 as a whole, foreign

debt inflows amounted to $8.65 billion, out of which

as much as $4.18 billion came in the month of December.

On the other hand, calendar 2011 is said to have recorded

a net outflow of equity investments to the tune of

$357 million. Moreover, foreign debt inflows in January

are placed at $3.21 billion against a much smaller

$1.7 billion of equity inflows.

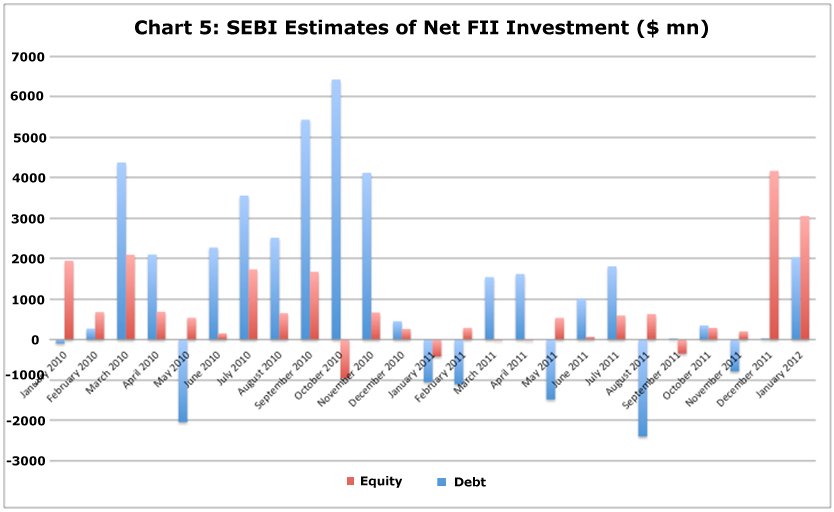

Finally, SEBI figures on net FII investment suggest

that while FII investments in equity have been low

or negative for much of the past 14 months, FII purchases

of debt instruments have spiked during December 2011

and January 2012.

Chart

2 >>

(Click to Enlarge)

What does this combination of figures say about the

capita inflows into the country and their role in

financing the current account deficit? To start with,

they do point to the fact that, over the last year,

inflows of equity investment have been less buoyant

than they were prior to the financial crisis and during

the post crisis recovery. Secondly, they indicate

that one consequence of this has been an enhanced

role for foreign debt in financing the current account

deficit.

Chart

3 >>

(Click to Enlarge)

However, this does not mean that India is having any

difficulty financing its current account deficit,

nor that increased reliance on debt is driven purely

by the need to finance the current account deficit.

Rather large Indian firms are choosing to borrow abroad

to benefit from the substantially lower interest rates

in international markets as compared with India. Moreover,

the government had in December deregulated interest

rates on Non-Resident (External) rupee (NRE) deposits

and Ordinary Non-Resident (NRO) Accounts, triggering

a chase for non-resident deposits among Indian banks.

According to reports, there has since been a surge

in NRI deposits, encouraged by the opportunity to

earn profits through arbitrage. This makes the volume

of debt inflow much greater than needed to finance

the current account gap. As a result, foreign exchange

reserves have risen and remained at relatively high

levels.

Chart

4 >>

(Click to Enlarge)

Despite these factors the government and the RBI appear

to be using the shift away from equity to debt inflows

to liberalise the terms for foreign equity investment

inflows. Flagging this tendency was the announcement

on New Year's day 2012 that a new group of foreign

investors identified as Qualified Foreign Investors

(QFIs) are to be permitted to invest directly in India's

equity markets. The definition of who ‘qualifies'

is rather broad: it covers any individual, group or

association resident in a foreign country that complies

with the Financial Action Task Force's (FATF) standards

and is a signatory to the multilateral Memorandum

of Understanding of the International Organisation

of Securities Commissions (IOSCO), dealing with regulation

of securities markets.

Measures such as these are partly explained by the

UPA government's desire to establish that it has not

slowed down on reform and to counter the view that

a form of ''policy paralysis'' afflicts it. But they

are also driven by the need to reverse the slow down

in inflows of foreign portfolio investment. The decline

in FII inflows has been attributed to developments

abroad, which required foreign institutional investors

to book profits in India and repatriate their funds

to meet commitments or cover losses at home. The presumption

appears to be that individual investors would not

be affected by such compulsions. The government's

press release announcing the new QFI policy declares

that the object of the measure is to ''to widen the

class of investors, attract more foreign funds, and

reduce market volatility''. In the last Budget these

investors had been allowed to invest in Indian Mutual

Fund Schemes. The recent announcement takes this a

step further and treats them on par with FIIs. The

government's view that QFIs would make up for any

loss of FII inflows and that their investment would

be characterised by greater stability has to be tested.

But the factors motivating its decision are clear.

Chart

5 >>

(Click to Enlarge)

One danger is that the new measure allows direct access

to equity markets to entities not regulated in their

home country. When India first began permitting foreign

investment in the equity market, the FII category

was created to ensure that only entities that were

regulated in their home countries would be permitted

to register and trade in India. The logic was clear.

Since it is impossible for Indian regulators to fully

rein in these global players and impose conditions

on their financing, trading and accounting practices,

controlling unbridled speculation required them to

be regulated at the point of origin.

But this kind of derivative regulatory control can

apply, if at all, only to institutional investors.

Individual investors cannot be subject to such rules

even in their home country and allowing them to enter

amounts to giving up the requirement that only foreign

entities subject to some discipline and prudential

regulation should be allowed to trade in Indian markets.

This is of relevance because individual investors

are unlikely to enter India and invest in equity to

hold it with the intention of earning dividend incomes.

The exchange rate and other risks would be deterrents

to such long-term commitments. If such investors do

come it would be with the intent of reaping capital

gains through short-term trades. Thus, to the extent

that the measure is successful it would mark a transition

towards allowing speculative players greater presence

in Indian markets. Defending that on the grounds that

it would help reduce dependence on debt is indeed

questionable.

*This

article was published in the Business Line on January

9, 2012.