Can Asia Decouple?*

When

the Global Financial Crisis struck in 2008, there were many analysts

who argued that some developing countries – especially in developing

Asia and in particular China – could not only avoid the adverse effects

of the crisis but also emerge as an alternative growth pole for the

world economy. The extent to which economic ''fundamentals'' quickly

unravelled across the developing world came as a surprise to them, as

falling exports and dramatically reversing capital flows caused economic

distress in many countries and affected even the strongest of them.

Even in countries like China that were earlier seen as relatively immune,

only very proactive countercyclical measures, including fiscal stimulus

packages and very substantial monetary and credit easing, allowed the

growth momentum to be restored.

Nevertheless, it is certainly true that in many parts of the developing

world, and especially Asia, the recovery was faster and sharper than

was experienced in the North. In China and India, average incomes did

not fall but continued to grow, albeit at a slower rate. By 2010 it

was being argued that in these large countries and elsewhere, the growth

engine was increasingly decoupled from the sputtering and hesitant recovery

that was evident in the northern countries.

Now that prospects for the world economy are once again looking gloomy,

the relatively quick recovery in several developing countries is being

seen as a potential alternative source of expansion. As the US gets

enmeshed in politically determined fiscal constraints and the eurozone

crisis plays out to create chronic economic weakness and potential disaster

in Europe, it is clear that expecting any positive stimulus from these

two large regions is misplaced. Instead, eyes are turning towards the

BRICs, or to the region of developing Asia, to provide another growth

pole in what will otherwise be a sagging and even dismal global economic

story.

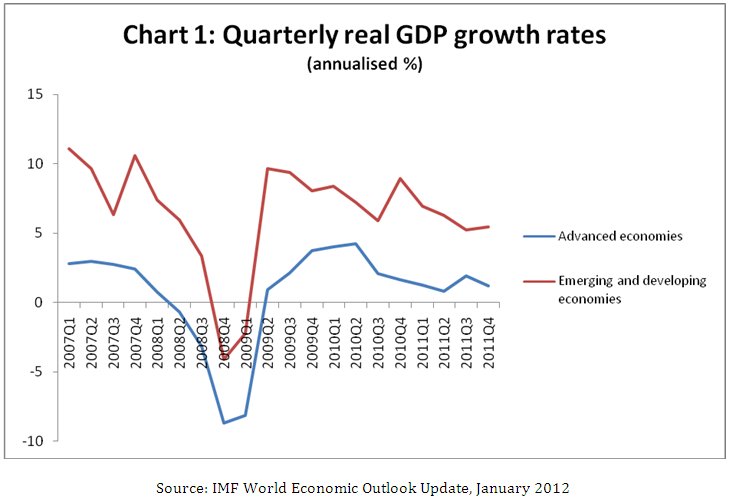

To what extent are such hopes justified? Consider the recent trends

in growth and investment, as shown in Charts 1 and 2. As is evident

from Chart 1, while overall GDP growth rates in emerging and developing

economies remained higher than in the advanced countries, they also

turned negative in the last quarter of 2008 and the first quarter of

2009. What is more striking is the synchronicity of even quarterly changes,

between the advanced and developing economies.

It is true that the divergence between the two groups of economies has

grown slightly in the last few quarters, but the difference is still

less than it was in 2007, during the global boom. More significantly,

the direction of movement appears to be similar for both categories

of countries, suggesting that the forces impelling change are still

largely determined by what is going on in Northern economies.

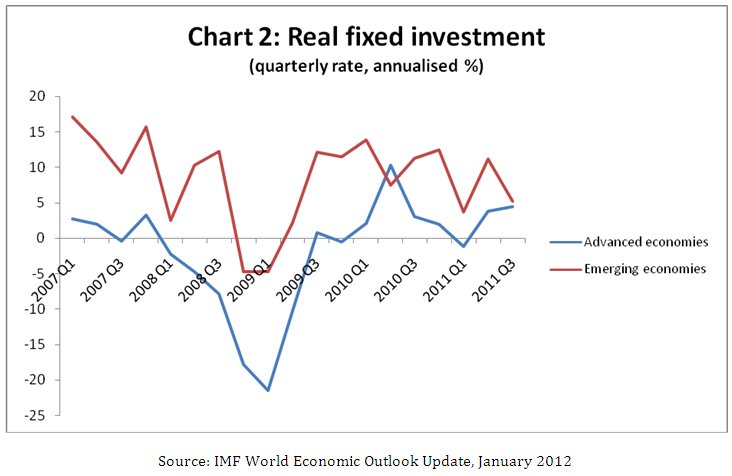

In the period just before and after the Great Recession, a similar story

seemed to be the case for fixed investment rates. However, since the

middle of 2009 the picture of fixed investment seems to have been more

mixed. Even so, the dampening effect on investor expectations, emanating

from the gloom in developed markets, is evident.

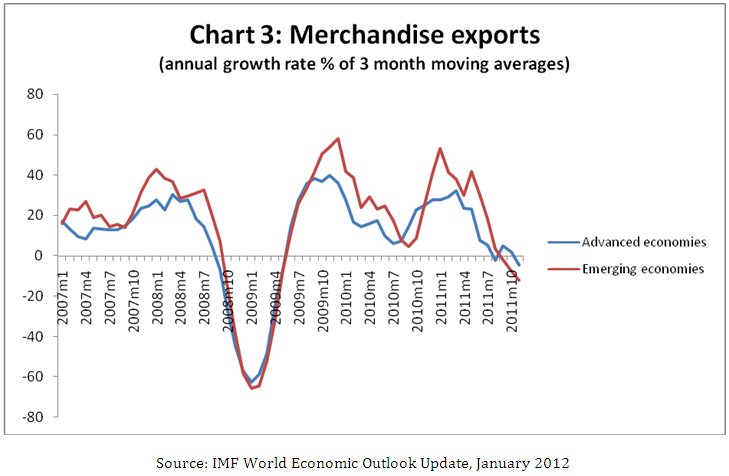

Presumably one reason for the gloom is the impact that the slowdown

in the US and Europe has on exports of developing countries. Here the

story – described in Chart 3 - is unambiguous and depressing. Export

growth rates from both advanced and developing countries tend to move

in tandem, and if anything, merchandise exports of developing countries

(in value terms in this chart) have been even more volatile and fallen

even more sharply, including in the very recent past.

Incidentally,

the picture would look even bleaker if services exports were to be included,

since service exports have experienced substantial deceleration in the

recent past. This includes not just those services that are affected

by the slowdown in trade (such as transport and related services) but

also a range of other more employment-intensive activities such as tourism

and IT-enabled services. Clearly, there is little sign of decoupling

in trade.

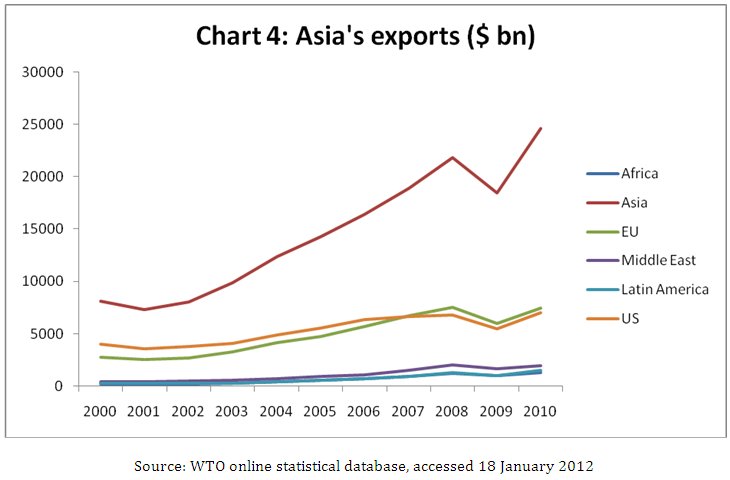

But suppose we consider specifically Asia, which is still widely considered

the most dynamic region. There has been much talk of how greater integration

within developing Asia has already generated new patterns of trade,

investment and economic activity, and that therefore increased Asian

integration will provide more stimulus to growth in the region even

if other areas stagnate.

There is no doubt that intra-Asian trade has increased significantly

in the recent past. As Chart 4 indicates, since the turn of the century,

Asian exports within the region have not only been larger but have significantly

outpaced exports to other major trading partners or regions. Even though

there was a break in the upward trajectory in the crisis year of 2009,

the subsequent revival of intra-regional trade suggests that there is

still a lot of inherent dynamism.

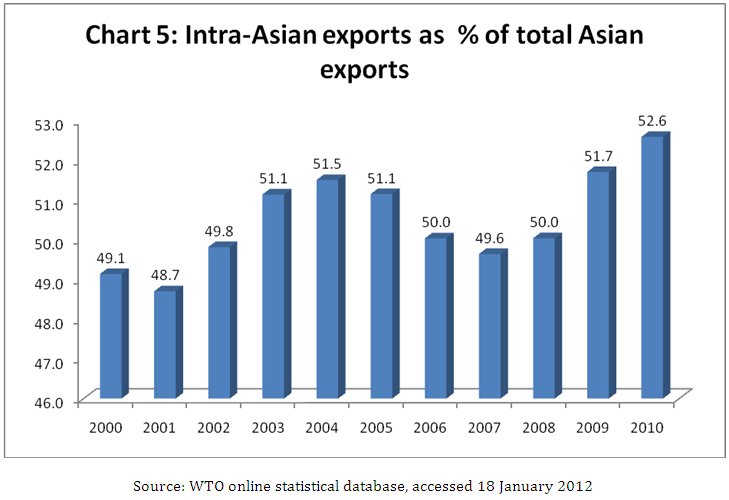

But still, it should be borne in mind that even though intra-regional

trade has increased, it is still only around half of all of Asia's exports.

Chart 5 shows that while there have been changes in the share of intra-regional

trade, with increases in the recent past, in this period it has been

volatile around a fairly narrow band, fluctuating between 49 and 52

per cent of total exports.

This means that global currents are still very significant in determining

trade patterns, particularly exports. And since so many countries in

the region are highly trade-dependent and have generally chosen export-oriented

growth as the model, the slowdown in exports will necessarily also affect

levels of economic activity, employment and future investment.

More than the quantitative indicators, it is also the pattern of integration

and the quality of the activity that is important in this. Much of the

rapid increase in intra-regional trade in developing Asia has been because

of the emergence of a multi-location multi-country export production

platform, largely organised around China as the final processor. This

is why more than four-fifths of such trade consists of intermediate

goods used in further production, rather than final demand.

Such trade is obviously closely linked to the behaviour of the ultimate

export markets, which still remain dominantly in the North, despite

recent changes in the direction of trade. Thus, for example, China (which

is the fulcrum of much of this kind of export-oriented activity) still

looks to the US and the European Union for just under 40 per cent of

its total exports. Reduced demand from these areas will translate into

reduced demand for raw materials and intermediates required for processing

into goods for these markets. There is already some scattered evidence

that this process has begun.

This suggests that expectations of Asia being able to blithely withstand

the latest round of economic crisis are not just over-optimistic but

probably wrong. It also means that Asian governments have to be prepared

for this with proactive measures to cope, and that business as usual

simply will not work in the evolving global scenario.

*This

article was originally published in the Business Line on 20 February,

2012 and is available at

http://www.thehindubusinessline.com/opinion/columns/c-p-chandrasekhar

/article2913493.ece?homepage=true