Themes > Features

20.01.2004

Bank Reform and the Rural Sector

In the

period before the nationalisation of banks, key sectors

of the economy including agriculture remained thoroughly

neglected in terms of availability of institutional

credit. Whereas the industrial sector at that

time accounted for about 15 per cent of national output,

it appropriated two-thirds of commercial bank credit,

whereas the agricultural sector contributing about half

of national output was almost completely neglected by

the commercial banks.

One of the most important objectives of government policy

since the nationalisation of 14 commercial banks in

1969, was to extend and expand credit not only to those

sectors which were of crucial importance in terms of

their contribution to national income and employment,

but also to those sectors which had been severely neglected

in terms of access to institutional credit. The

sectors that were initially identified for this purpose

were agriculture, small industry and self-employment.

These sectors were to be accorded priority status in

credit allocation by the banks.

As a consequence, policies such as interest rate controls

and pre-emption of resources through directed credit

programmes aimed at agriculture and the small scale

sector increased in magnitude during this period. There

was also a concerted effort at substantially expanding

the reach of the banking system, especially to the rural

areas. The success of policy in terms of branch expansion,

mobilisation of household savings, diversification of

lending targets and direction of credit to the priority

sector was substantial.

Yet, by the late 1980s, the banking sector in India

was faced with criticism of a completely different kind.

The focus of that criticism was the low profitability,

low capital base, high non-performing assets and the

ostensible "inefficiency" of and lack of transparency

in the banking system. Such criticism constituted the

point of departure of the Committee on the Financial

System (CFS) under the chairmanship of M. Narasimham

established in 1991 to pave the way for the liberalisation

of banking practices.

Among other things, this Committee recommended a reconsideration

of the policy of directed investments and directed credit

programmes, as well as the interest rate structure pertaining

to these. Thus it suggested that priority sector

credit as hitherto defined should be phased out. It

also recommended that the concept of priority sector

itself be re-defined to target only the truly needy,

viz. the small farmer and the tiny sector in industry

and that the credit to this redefined priority sector

should be only 10 per cent of total bank credit.

On interest rates, the Committee suggested that the

complex system of administered interest rates be dismantled

in a phased manner and that there should be greater

reliance on the market mechanism so that interest rates

could be allowed to perform, in a greater measure, their

allocative function.

As the erosion of profitability was not only due to

factors operating on the income side, but also on the

side of expenditure of banks, the committee wished that

without prejudice to the availability of banking facilities

especially in the rural areas there should be a reconsideration

of the future of unremunerative branches. In the

Committee's view, judgement relating to future expansion

of branches should primarily be left to banks themselves

and accordingly branch licensing by the Reserve Bank

should be abolished.

When recommending financial liberalisation as a solution

to the "problem" of low profitability, there

was the immediate problem of dealing with the existing

large element of non-performing assets in banks' portfolio.

Subjecting banks that had hitherto functioned under

a completely different discipline to market-based competition

and the threat of closure would have amounted to discrimination

vis-à-vis new entrants with adequate resources.

The Narasimham Committee coined a new definition of

NPAs that was in conformity with international practice.

From 1991-92, banks had to classify their advances into

four groups such as (i) standard assets; (ii) sub-standard

assets; (iii) doubtful assets and (iv) loss assets,

and indicated that the advances classified under the

last three groups were to be considered as NPAs.

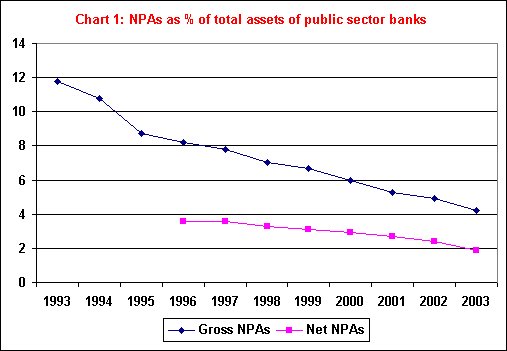

Chart 1 shows the NPAs of public sector banks between

1993 and 2001 , as a proportion of total assets. It

shows that the proportion of total NPAs to total advances

declined from 23.2 per cent in March, 1993 to 12.4 per

cent in March, 2001.

The sharp decline in NPAs of public sector banks during

1996-97 was really due to a definitional change.

RBI introduced a new concept of "net NPAs"

in 1996-97 in place of gross NPAs followed by it earlier.

This was derived by deducting various items, including

"total provisions held", exclusion of which

conceals the gross damage caused by the NPAs on the

banks.

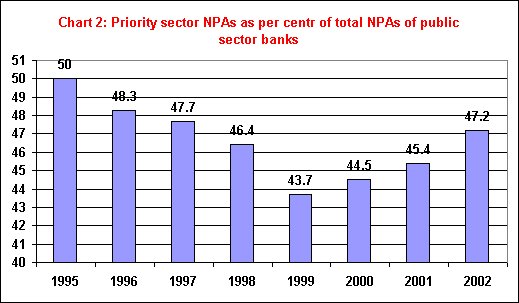

Chart 2 indicates that the share of the priority sector

in total NPAs for public sector banks decreased until

2000, even though the proportion of total NPAs accounted

for by the priority sector was inflated by the new method

of calculating net NPAs. Subsequent increases have been

due to the broader scope of priority sector lending,

as explained below.

Also, NPAs resulting from small advances (i.e. where

outstanding bank loans amounts to Rs. 25,000 or less)

have been declining and that too quite sharply in relative

terms. The recovery performance of direct agricultural

advances had been improving, especially in the first

half of the 1990s. According to the RBI, the recovery

performance of direct agricultural advances had increased

from 54.1 per cent in 1992 to 59.6 per cent in 1995.

The policies initiated by the RBI, which implicitly

treat agricultural advances as prone to result in NPAs

should be viewed against this backdrop. An informal

working group set up by the RBI in 1992-93 to consider

any required relaxation in the implementation of new

prudential norms had recommended that in the case of

advances granted for agricultural purposes, banks should

adopt the agricultural season as the basis for treatment

of NPAs. Accordingly, it was decided that any agricultural

advance should be treated as NPA only when interest/instalment

is not paid continuously for 2 half-years, synchronising

with the harvest.

This decision was reversed in April 1997 when the RBI

advised the banks to reduce the interest overdue period

of two half-years in the case of agricultural advances,

to two quarters i.e. from 12 months to six months, from

1997-98 onwards. This was bound to accelerate

the process of agricultural loans getting increasingly

classified as NPAs and negate the effect of the continuous

increase in the recovery performance of agricultural

loans.

Priority

Sector Lending

However, the argument

of high NPAs was used to encourage banks to cut back

on lending to the priority sector. Among the directed

credit programmes followed by the banks, priority sector

lending has been perhaps one of the most effective.

In 1969, banks provided only 14.6 per cent of their

total credit to the priority sectors, with the percentage

of credit disbursed to agriculture being only 5.4 per

cent. In 1991, 40.9 per cent of net

bank credit was advanced to priority sectors, and total

credit to agriculture, even though remaining below the

prescribed level of 18 per cent, was 16.4 per cent by

1991.

Unfortunately, since 1991, there has been a reversal

of the trends in the ratio of directed credit to total

bank credit and the proportion thereof going to the

agricultural sector, even though there has been no known

formal decision by government on this score. At

the same time, serious attempts have been made in recent

years to dilute the norms of whatever remains of priority

sector bank lending.

As mentioned earlier, the Committee on the Financial

System (CFS) recommended phasing out of the bulk of

priority sector targeting by the banks. The changes

recommended by the committee in the field of priority

sector lending were as follows:

The directed credit programmes should cover a redefined

priority sector consisting of small and marginal farmers,

the tiny sector of industry, small business and transport

operators, village and cottage industries, rural artisans

and other weaker sections.

Credit targets for this redefined priority sector should

be fixed at 10 per cent of aggregate bank credit.

Stipulations of concessional interest to the redefined

priority sector should be reviewed with a view to its

eventual elimination, in about three years.

A review should be undertaken at the end of three years

to see whether the directed credit programmes need to

be continued.

While the recommendations of the Narasimham Committee

on priority sector lending were not completely accepted,

various policy measures, aimed at diluting the norms

of priority sector lending were adopted, so as to ensure

its gradual phase-out in the future.

While the authorities have allowed the target for priority

sector lending to remain untouched, they have widened

its coverage. At the same time, shortfalls relative

to targets have been overlooked. In agriculture,

both direct and indirect advances to agriculture were

clubbed together for meeting the agricultural sub-target

of 18 per cent in 1993, subject to the stipulation however

that "indirect" lending to agriculture must

not exceed one-fourth of that lending sub-target or

4.5 per cent of net bank credit.

It was also decided to include indirect agricultural

advances exceeding 4.5 per cent of net bank credit into

the overall target of 40 per cent. The definition

of priority sector itself was also widened to include

financing and distribution of inputs for agriculture

and allied sectors (dairy, poultry, livestock rearing)

with the ceiling raised to Rs. 5 lakh initially and

Rs. 15 lakh subsequently. The scope of direct agricultural

advances under priority sector lending was widened so

as to include all short-term advances to traditional

plantations including tea, coffee, rubber, and spices,

irrespective of the size of the holdings.

Apart from this, there were also totally new areas under

the umbrella of priority sector for the purpose of bank

lending. This meant that banks defaulting in meeting

the priority sector sub-target of 18 per cent of net

credit to agriculture, would make good the deficiency

by contributing to various other institutions such as

the Rural Infrastructure Development Fund of NABARD.

They could also make investments in special bonds issued

by institutions like State Financial Corporations and

treat such investments as priority sector advances.

The changes thus made in the policy guidelines on the

subject of priority sector lending were obviously meant

to enable the banks to move away from the responsibility

of directly lending to the priority sectors of the economy.

It is in the light of this that the trends in priority

sector lending during the post liberalisation period

of 1991-2001 should be understood.

Priority sector lending as a proportion of net bank

credit, after reaching the target of 40 per cent in

1991, had been continuously falling short of target

till 1996. It has subsequently been in excess of the

target for the reasons specified above, and stood at

43 per cent in 2001, which was mainly due to the

inclusion of funds provided to

Regional Rural Banks by their sponsoring

banks, that were eligible to be treated as priority

sector advances. Advances to agriculture

also declined from 16.4 per cent in 1991 to 15.3 per

cent in 2002, well below the target of 18 per cent of

net bank credit. In the year ending March 2003, direct

agricultural advances amounted to only 10.8 per cent

of net public sector bank credit.

The

fall in the ratio of priority sector lending to deposits

from 26.6 per cent in 1991 to 22.8 per cent in 2001

was partly due to the decline in the overall credit

deposit ratio of banks and partly due to the decline

in the ratio of priority sector advances to total bank

credit.

Private banks in general and foreign banks in particular

have been lax in meeting regulatory norms. The sector

most affected was agriculture, in whose case private

bank lending amounted to just 10.8 per cent of net credit,

which was far short of the stipulated 18 per cent in

the year ending March 2003. Direct agricultural advances

were only 6.3 per cent of net private sector bank credit.

Within the private sector, the foreign banks were the

major defaulters. According to the annual report of

RBI, the advances of foreign banks to the priority sector

were only 34 per cent of net credit in the year ending

March 2003. Here again, agriculture was the prime area

of neglect. Foreign banks' performance on credit to

the small scale industries and export sectors was much

better, with lending to these sectors accounting for

9 and 19 per cent, respectively, of the net bank credit

against the sub-sectoral targets of 10 per cent and

12 per cent.

Clearly, even to the extent that priority-sector lending

targets had been met, the choice was in favour of the

more cost effective and profitable sectors. Overall,

nearly 60 per cent of the priority sector lending by

foreign banks was directed towards export credit.

The difficulty is that, faced with the demands made

on them by the advocates of liberalisation and the effects

of competition from the private sector banks, banks

in the public sector are also being forced to change.

They are trying to trim operating expenses, by reducing

the wage bill by reducing employment through retrenchment

under the VRS scheme and computerisation. They are also

seeking to reduce costs by limiting branch expansion

and reducing the number of bank branches.

The latter, which affects the rural areas first, reduces

access to credit in rural areas that were well-served

by the post-nationalisation branch expansion drive,

and worsens the tendency towards reduced provision of

credit to the agricultural sector.

In consequence of all this, the formal credit squeeze

upon Indian agriculture is now acute. This has led to

severe problems of accessing working capital for cultivators,

and has also meant the revival of private money lending

in rural areas. Such retrogression has extremely disturbing

implications for the future of Indian agriculture.

© MACROSCAN

2004