The Contentious World of Agricultural Trade

Agriculture,

including activities allied to it, has a rather divergent role in economies

across the world. To start with, there is a great diversity in the share

of agriculture as a percentage of GDP, with the figure varying from

52 percent in Laos, for example, to just 6 percent in Korea. Similar

differences exist with regard to the share of agricultural employment

in total employment. Generally, the lower the GDP, the higher is the

significance of agriculture in the economy. This also means that engaging

in world agricultural trade despite its distortions would have the largest

impact on the poorest countries in the world.

However, the role of trade should not be exaggerated. Though the global

market for agricultural commodities is estimated at $600 billion, the

share of that market serviced through cross-border trade is small. As

Einarsson has argued, there is a basic difference here between staples

and commercial plantation crops.[1] Much of the world’s population obtains

staples from domestic production in their countries of domicile. Of

the staple foods, it is only in wheat that global trade is consistently

above 10 percent of total world production. And only in a few of the

typical plantation crops does global trade represent more than 50 per

cent of world production (Table 1).

Table

1: Approx. share of world production of selected agricultural products traded across borders |

|||||

Coffee |

80%

|

||||

Tea |

40%

|

||||

Cotton |

30%

|

||||

Soybeans |

30%

|

||||

Sugar |

30%

|

||||

Bananas |

20%

|

||||

Wheat |

17%

|

||||

Feed

grains |

11%

|

||||

| Rice | 6% |

||||

Overall,

agricultural trade takes place largely between developed countries,

which account for about 70 percent of both world exports and imports.

Yet, there are three reasons why the level and pattern of global agricultural

trade has important implications for developing countries. To start

with, exports of plantation crops and tropical products of various kinds

are crucial sources of foreign exchange earnings for many developing

countries. This is the group that Tim Groser, the Chairman of the WTO’s

Committee on Agriculture describes as the developing countries with

''offensive'' or ''export'' interests. They ''either already have substantial

economic interests, relative to their economies, in world agriculture

markets and can build on this''; or, ''they can see a future for themselves,

once the massive trade distortions are either eliminated or substantially

reduced.''

The second reason why trade is important for some developing countries

is that they either depend on imports of staples to meet domestic consumption

or their currently prevalent food security is threatened by agricultural

trade liberalisation, inasmuch as cheap imports can result in a sharp

decline in domestic production of staples or the promise of quick profits

may encourage rich farmers and agribusiness interests to ensure or encourage

production of more profitable commercial crops.

Globally, not only is a small share of production of food staples traded,

but exports of food staples are dominated by a very small group of countries

which have been described as "natural exporters", such as

Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, New Zealand, Uruguay, and the

USA. These are countries where favourable geographical conditions, sparse

populations and a very specific experience with colonisation, have encouraged

a large-scale and extensive agriculture that delivers substantial surpluses

of these staples. Production costs here are far lower than elsewhere

making them ''natural exporters''. The only exception to these conditions

among global exporters of staples is Europe, where, as widely recognised,

state support to farmers has been responsible for ensuring the availability

of exportable surpluses.

What is noteworthy is that only a few developing countries that figure

among the group of natural exporters are significant exporters of grains

or animal products. They are Thailand (rice and poultry), Vietnam (rice),

Argentina (wheat, feed grains, soybeans, beef and milk powder), Brazil

(soybeans, beef and poultry) and Uruguay (beef). The net result of this

phenomenon is a peculiar distribution of exporters and importers of

food products between the developed and the developing countries. Over

80 percent of globally traded rice and wheat is imported by developing

countries, as is a sizeable portion of feed grain and soybean exports.

Few developing countries import animal products. The one exception is

powdered milk, a low-value surplus product, of which 85 percent of world

trade goes to the South. And all the high-value animal products such

as beef, pork, poultry and cheese are traded either between developed

countries or from South to North.

Thus in the realm of trade in staples developing countries can be divided

into three rather distinct groups: (i) a small group of exporters, consisting

of "natural exporters" that can compete with developed countries

on the global markets for wheat, feedstuffs and animal products and

a few with higher population densities and more traditional agricultural

structures that are also consistent net exporters, such as Thailand

and Vietnam; (ii) a large majority of developing countries which belong

to a group that thus far has been more or less self-sufficient in food-though

many of these countries may more often buy food from global markets

rather than sell food in those markets, they are not chronically dependent

on food imports and most often are in a position to finance those imports

with foreign exchange revenues from the export of other agricultural

products, typically tropical plantation crops; and (iii) a significant

number of net importers that are chronically dependent on the world

market for basic food supply-many of which are also among the world’s

poorest countries (LDCs).

It is indeed true that over time developing countries have been adjusting

their export profiles depending on trends in global trade. In response

to declines in the prices of tropical products, the middle-income developing

countries have reduced the share of tropical beverages and raw materials-coffee,

tea, cocoa, sugar, cotton and tobacco-in their agricultural exports.

That share has fallen from 55 per cent in the 1960s to 30 per cent by

1999-2001. They have turned to the export of more high value food products-vegetables,

fish, meat, nuts and spices. These now account for more than 50 per

cent of their agricultural exports. However, the financial and technological

requirement for switching over to higher value food crops are clearly

beyond the resources of farmers in the LDCs. Hence, the LDCs as a whole

saw their reliance on raw materials and tropical beverages increase-from

59 per cent in the 1960s to 72 per cent by 1999-2001. In the event,

the pattern of trade dependence of the kind delineated above has only

got accentuated.

These features of agricultural trade imply that changes in agricultural

trade rules relating to staples can affect developing countries in three

different ways. They can increase dependence on imports of staples of

developing countries, since countries that currently do not import but

access adequate supplies through domestic production backed by protection

and support measures would find domestic production displaced by imports.

They could affect the access of the few developing country exporters

to global markets, by allowing for so-called non-trade distorting support

for developed country farmers in the EU and US, which restricts imports

into those regions. They could raise the prices at which those already

dependent on imports of staples can access those commodities. Thus there

is reason to believe that only the few developing countries that are

competitive exporters of staples would wholeheartedly support liberalisation

of trade in staples.

The other group of supporters of a more liberal trade regime would be

the exporters of tropical and non-food products in the export of which

they have an ''offensive'' interest. These countries could believe that

better market access and reduced domestic support in the developed countries

could helps increase the volume of their exports as well as push up

prices.

However, most developing countries would be wary about agricultural

trade liberalisation because of the threat to livelihoods and food security

that the process could imply.

The Asian Experience

All these features of agricultural trade are illustrated by the trade

involved of countries in the Asia-Pacific region. Asian countries are

by no means dominant participants in the world trade in agricultural

products (Table 2). Only one Asian country (China) features among the

top ten global exporters of agricultural products, at rank 9. In fact,

Brazil and China are the only two developing countries among the top

ten. If we consider the set of countries which each account for 1 percent

of world exports of agricultural products, they include the following

from the Asia-Pacific: China, Australia, Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia,

New Zealand and India. Vietnam, Japan, Hong Kong, Rep. of Korea, Chinese

Taipei and Singapore have world market shares between 0.5 percent and

less than 1 percent.

Table

2: Leading Agricultural Exporters in the Asia-Pacific |

||||||

Country |

$

mn |

Mkt

Share |

||||

China |

22158 |

3.3 |

||||

Australia |

16337 |

2.4 |

||||

Thailand |

15081 |

2.2 |

||||

Malaysia |

11061 |

1.6 |

||||

Indonesia |

9942 |

1.5 |

||||

New

Zealand |

9603 |

1.4 |

||||

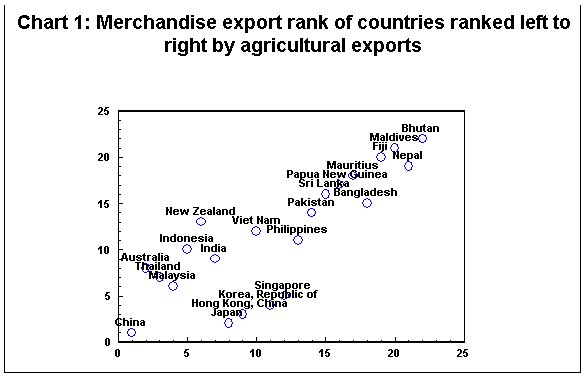

The implication of this should be clear: Asia-Pacific countries are by no means significant influences on global trade and therefore their strength in global negotiations is by no means substantial. But the reverse is also true: few Asia-Pacific countries are dependent on agricultural exports for their export revenues. Chart 1 plots countries according to their ranks as merchandise exporters and agricultural exporters. If a country falls along the diagonal (45 degree line) its rank as a merchandise exporter tallies with its rank as an agricultural exporter. Interestingly, this is not true of countries that hold the high ranks in either category, excepting for China. In the case of countries such as Japan, Korea, Hong Kong and Singapore, they rank high as merchandise exporters but not as agricultural exporters. That is, the truly successful Asian exporters have not earned that success based on agricultural exports, excepting for countries like China. On the other hand, important agricultural exporters such as Australia, Thailand, Indonesia and New Zealand are by no means among the top merchandise exporters in Asia.

This could result in a substantial degree of difference in the approach

that countries in the Asia-Pacific region adopt with regard to the trade

negotiations-while exporters like Australia, New Zealand, Thailand and

Vietnam would want substantial liberalisation of agricultural trade

involving all three pillars-market access, domestic support and export

competition-many others may be more interested in limiting agricultural

trade liberalisation in order to protect domestic livelihoods and ensure

food security.

These features of the Asia situation are reflective of differences among

developing countries as a group in the global negotiations, since the

structures of agricultural production and trade at the global level

are the same. Thus if there is still some degree of solidarity in the

developing country camp, it comes from three sources: first, the desire

of the developed countries to protect their agriculture, while demanding

greater agricultural and non-agricultural market access in the developing

countries; second, the belief among developing countries that there

must be adequate safeguard measures especially for ''sensitive'' products

in order to protect livelihoods and ensure food security; and, third,

the conviction that there must be a degree of differential treatment

for developing countries, especially the poorest amongst them.

On the question of developed country protectionism, the evidence is

indeed overwhelming. The OECD report on Agricultural Policies in OECD

Countries: Monitoring and Evaluation released in June 2005 states: ''There

has been little change in the level of producer support since the late

1990s for the OECD as a whole. It has fallen from 37 percent of farm

receipts in 1986-88 to 30 percent in 2002-04, but this level of support

was first reached seven years ago in 1995-97.'' That, we must recall

was almost at the beginning of the implementation of the Uruguay Round.

This constancy in support has been ensured in large part by ''box shifting''

or by the substitution of support measures that are considered trade

distorting, by those that are supposedly not. In 2004, the value of

support to producers in the OECD as a whole is estimated at USD 279

billion or EUR 226 billion. As measured by the percentage PSE, support

accounted for 30 percent of farm receipts, the same level as in 2003.

Including support for general services to agriculture such as research,

infrastructure, inspection, and marketing and promotion, total support

to the agricultural sector was equivalent to 1.2 percent of OECD GDP

in 2004.

This protectionism in the North has helped ensure a degree of solidarity

in the developing country camp. Not surprisingly, G-33 Ministers who

met in Jakarta on 11 and 12 June 2005 to assess the progress of the

agriculture negotiations declared that: ''the problem of food and livelihood

security as well as rural development constitute a concrete expression

of developing countries’ right to development and therefore require

a comprehensive solution in all three pillars of the agriculture negotiations.''

They also ''reiterated that the concepts of Special Products (SP) and

Special Safeguard Mechanism (SSM) as provided for in the July 2004 framework

are fundamental to any meaningful operationalization of Special and

Differential Treatment, and crucial for addressing food and livelihood

security as well as rural development needs of developing countries.

They emphasized that SP and SSM are key policy instruments for securing

the survival of the vast number of small farmers and the rural poor.

Therefore modalities on this matter shall be finalized by the Hong Kong

Ministerial.''

It appears that Tim Groser, the Chairman of the WTO’s Committee on Agriculture,

is sensitive to these demands of the developing countries. He states

in his status report on the agricultural negotiations released on 27

June 2005: ''Many developing countries, and particularly LDCs, have

deeply vulnerable people dependent on agriculture. Integrating these

parts of their agriculture sectors into any emerging reform framework

is deeply sensitive. Such sensitivities have to be accommodated as the

reform process takes shape.''

However, in what is called the ''first approximation'' or the structure

of agreement that has to be arrived at on all three pillars by July

31, 2005 as a basis for the ''political phase'' of discussions from

September to December, he feels that all features of the instruments

designed specifically to take account of the realities of much developing

country agriculture, such as SSM, cannot be addressed.

Past experience suggests that this may not be just a postponement, but

a tactic to delay discussions on issues on which the developed countries

will not give in and then demand that developing countries should be

reasonable and not derail agreement at the Ministerial on account of

such issues. If so, the limited solidarity within the developing country

camp must be used to stall progress along lines that reproduces the

inequities inherent in the Uruguay framework.

[1] Refer Einarsson,

P., 2001 ''The Disagreement on Agriculture''. Seedling 18.