Themes > Features

26.07.2006

Fallacies and Silences in the Approach to the Eleventh Plan

C.P. Chandrasekhar and

Jayati Ghosh

It

has already been pointed out in a previous column that in its Approach

to the Eleventh Five-Year Plan, the Planning Commission has adopted an

uncritical ''trickle-down'' approach to economic growth, by making the

basic objective the achievement of a certain target annual GDP growth

figure - either 7.8 or 9 per cent per annum - and effectively assuming

that all social goals will be achieved by this.

This is almost criminal, since the same Approach Paper has tucked away in it the first official acknowledgement that until now the country has been told a fairy tale about poverty reduction during the 1990s. Until recently, the growth-first argument has made much of the contested official claim that poverty declined from 36 per cent in 1993-94 to 26 per cent in 1999-2000 or by 10 per cent over a 6 year period. It is now revealed that the comparable figure for 2004-05 is 28 per cent, which implies only 8 per cent reduction over a 11 year period. This implies that despite all the hype on growth, it is now official that the rate of poverty reduction after 1990 has been at only half the rate between 1977 to 1990.

So in fact it matters great deal whether the pattern of growth that in planned for is actually ''inclusive'' or not, and the Planning Commission should really have focused all its attention on ensuring that this most crucial of goals is achieved. However, the combination of silences and misplaced emphases on particular areas creates an overall approach which falls very far short of even envisaging truly inclusive growth. In particular, the Approach Paper fails to address or wrongly deals with five critical areas that are not only essential for inclusive growth but also the most burning policy issues of the present time. These areas are control over and loss of land; employment generation; agriculture and food security; health; and education.

The land question

For a while now, issues relating to land control and assets distribution had gone out of fashion in policy discussion. However, they were always critical in affecting ground realities, and now the issues involved are so pressing that they simply cannot be wished away and must be addressed directly by the state at different levels. It is not simply that the pattern of landownership and control has been concentrated and subject to a significant degree of gender discrimination. It is also that recent patterns of development have created much more dispossession and dislocation, especially among the peasantry and forest dwellers, and this has created not only much more material distress but also widespread social tension.

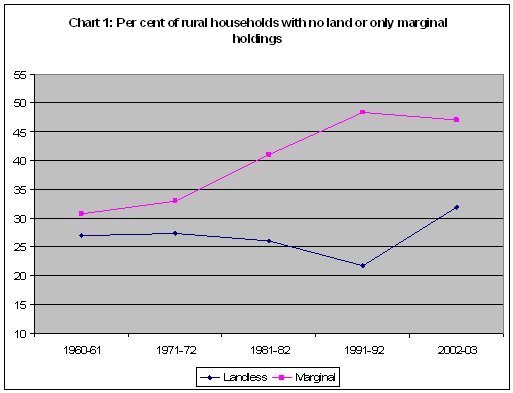

The NSS data on landholdings, as expressed in the data collected in the 59th Round of the survey and shown in Chart 1, indicate a significant increase in landlessness among rural households. According to these data, the proportion of landless rural households had been broadly stable for three decades from the early 1970s at around 28 per cent, and had come down to 22 per cent in 1991-92. But the data relating to 2002-03 indicate a very sharp increase to nearly one-third of rural households. A similar (and even more accentuated) increase had been evident from the NSS employment survey, which suggested that well above one-third of rural households had no land in 1999-2000.

This growing landlessness is not fortuitous: it is the result of a process that has been marked in the countryside over the last decade, of reduced economic viability of cultivation, that has particularly squeezed small producers. This is discussed in more detail below, but the moot point in this context is that financial stress, including the inability to repay loans taken for cultivation and for other purposes, has forced many farmers to sell their lands and join the landless population. This process is likely to have been especially strong among farmers with marginal holdings, which may explain why their proportion has fallen slightly in the most recent period.

In addition, the economic growth process has involved increasing displacement of people from their land, with inadequate or no compensation and rehabilitation measures. Such displacement has resulted not only from large irrigation projects but also for urban expansion, increases in transport networks such as roads and railways, and the like. Tribal populations have been disproportionately affected by this. The inadequacy of current rehabilitation practices, and the possibilities for social discord, have been recognised in the Approach Paper. But more needs to be done than simply ''frame a transparent set of policy rules'', and the Planning Commission should really have used this opportunity to reconsider the strategy of growth so as to ensure that displacement and dispossession are themselves minimised as far as possible. Instead, the Approach actually calls for dilution or removal of urban land ceiling acts by the state governments, thus reinforcing land monopolies of a few large players.

Despite these pressing and increasingly urgent concerns, discussion of land reforms - which are once again a topical issue - finds no place in the document. Nor is there any concern about the problem of recognising the land rights of women, and ensuring that women be given pattas in the event of any redistribution or rehabilitation.

Employment generation

Despite all evidence to the contrary - most obviously from the direct experience of the past and current Plan periods - the Planning Commission adopts a trickle-down approach whereby it is assumed that output growth will automatically generate more employment, and that too in sufficient quantities to meet the growing labour force. Yet it is obvious to all that the major failure of the growth process, and the most important impediment to ''inclusive'' growth, is the lack of adequate employment generation.

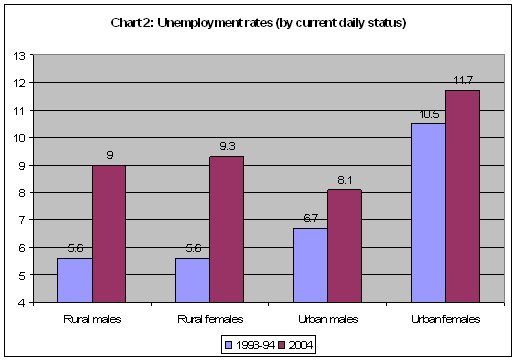

Recent NSS data, described in Chart 2, show a very sharp increase in open unemployment rates for men and women in both rural and urban areas, despite this being the period of highest recorded rates of aggregate output growth. In a country where there is no unemployment benefit and no social protection for those without jobs, and where most of the poor have no option but to find some work simply to survive, such an increase in open unemployment is remarkable and historically unprecedented. It points to a huge absence of productive income opportunities across both urban and rural areas. And it shows very clearly that ''trickle down'' cannot be relied upon to generate jobs.

Yet the discussion on employment generation is probably the weakest section of the Approach Paper, whereas it should have received the central focus. It is not listed at the start as among the most important challenges, and casual attitude permeates the rest of the document. There is no serious consideration of how to ensure that the growth process will actually create more jobs. Even worse, policies that will actually operate to reduce employment are strewn throughout the paper.

There is apparently a belief that labour market flexibility, which is a euphemism for reduced protection to workers in the organised sector, will automatically ensure more employment creation, even though more than 90 per cent of Indian workers currently have no protection at all, and there is little international or domestic experience to justify this hackneyed argument. Even while the Planning Commission effectively wants to remove protection from workers in the unorganised sector, there appears to be a general lack of concern with the fate of unprotected workers generally. Thus, it is surprising that the Approach makes no mention at all of an extremely important new initiative of providing social security to informal sector workers, that has been proposed by the National Commission on the Unorganised Sector in its recently released report.

The agrarian crisis and food security

The persistent crisis in agriculture is well known; indeed, the UPA government recognised it and insisted that greater policy focus on agriculture would form one of the basic elements of its economic strategy. More recently, the continuing and even increasing incidence of farmersí suicides in some particularly affected regions has prompted the announcements of specific relief ''packages'' which may have more cosmetic than real effects.

Nevertheless, the causes of the current agrarian distress are now widely recognised. The combination of continuously higher input prices and volatile output prices, along with reduced access to institutional credit and inadequate public attention to the problems of dryland farming, have created problems for all farmers, but obviously the smaller and financially weaker sections of the peasantry have been the worst affected. Even the measure that are necessary to deal with this are now known to state and central governments. In fact, the National Commission on Farmers headed by M. S. Swaminathan has made a series of important recommendations, both general and specific and long term as well as short term, to address this current crisis.

In this context, the very least that could be expected of the Planning Commission was that this context and the specific measures already available for discussion would be taken on board in the Approach Paper. Unfortunately, this does not seem to be the case. In fact, the discussion suggests that the important reports of the Farmersí Commission have not even been read carefully! The problems of agriculture are dealt with simplistically, based on the assumption that encouraging corporate farming and diversification into horticulture will be enough to make agriculture viable and buoyant again. The basic problems facing most farmers in the country, especially small peasants, are not addressed at all: rising prices of inputs and very volatile output prices; problems of access to assured water supply and difficulties of raising cash crops on dryland areas; the inadequate support to related activities such as livestock rearing; poor extension services which do not provide the latest or relevant information to farmers; the exclusion of the vast majority of petty cultivators such as tenant and women farmers, from the ambit of institutional credit; the inadequate protection provided by crop insurance schemes, and so on.

In addition to this, the real and growing problem of food insecurity has not received any attention at all. The dominant public perception is of major and disturbing changes in the food economy of India, given the recent need to import food grains, pulses and sugar for the first time in thirty years, as part of the measures to stem the steep rise in prices of essential commodities, as well as the evidence of growing hunger and even starvation reports from certain areas. The public distribution system has been run down and does not provide adequate access to the poor: it urgently needs expansion to be made universal. The expansion of the ICDS scheme and its nutrition component similarly is something that has even been mandated by the Supreme Court, although thus far the central government has not fulfilled its legal obligations in this matter. So the current context is one in which food security - both on the ground and at the macro level - should surely have been a priority among our planners. Surely, the Planning Commissioní s silence on this matter is deafening.

Health and education

These were declared to be the central concerns of the UPA government, and are associated with flagship programmes such as the National Rural Health Mission and progressive legislation such as the Right to Education Bill. yet even in these crucial social sectors, the mindset displayed in the Approach Paper is still very much that which was displayed by the earlier government, of raising user fees and reducing so-called ''subsidies'' in areas which must by publicly funded.

With respect to health provision, the Approach Paper talks of raising user charges, which is bound to exclude most of the poor in what is already a hugely underfunded public provision. In addition, there is an extraordinary suggestion to provide remuneration to public health workers by the service! Surely it is obvious that providing decent public services requires adequate numbers of decently paid personnel, without which the services are likely to be substandard. In a matter as crucial as health, linking pay to ''productivity'' or ''delivery'' however defined will not only militate against such workers, it will also create incentives of the most undesirable kind with unwanted social consequences.

Similarly, there is an argument for higher fees in higher education, despite the well known problems of social exclusion that can result from this and the presence of significant externalities that make higher education also clearly a merit good. Another problematic proposal relates developing a voucher system, which has been proposed not only for secondary and higher education but even for primary education. According to such a scheme, children would be provided with vouchers with which they could pay fees in private schools as well as public schools, thereby ''enlarging choice''. This idea, which comes from a failed US experience, completely ignores the stark realities of the government school system at present, which is desperately underfunded. Official estimates suggest that around one-fifth of schools do not have a building at all, and another one-fourth have only one room. More than 15 per cent of elementary schools function with only one teacher and another 20 per cent one fifth with only two teachers for five classes. In this appalling context, surely the priority in expenditure must be to provide more infrastructure, teachers etc. in public schooling, without which no quality improvements there are possible, and not to indirectly subsidise private schools.

There are numerous other problems with different suggestions made in the Approach. In general they stem from an underlying perception that creating a profitable environment for private sector functioning will be enough to fulfil most social goals, and no particular planning strategy is required for this. Coming from the organisation charged with handling public expenditure for development, this is a disturbing perspective.

This is almost criminal, since the same Approach Paper has tucked away in it the first official acknowledgement that until now the country has been told a fairy tale about poverty reduction during the 1990s. Until recently, the growth-first argument has made much of the contested official claim that poverty declined from 36 per cent in 1993-94 to 26 per cent in 1999-2000 or by 10 per cent over a 6 year period. It is now revealed that the comparable figure for 2004-05 is 28 per cent, which implies only 8 per cent reduction over a 11 year period. This implies that despite all the hype on growth, it is now official that the rate of poverty reduction after 1990 has been at only half the rate between 1977 to 1990.

So in fact it matters great deal whether the pattern of growth that in planned for is actually ''inclusive'' or not, and the Planning Commission should really have focused all its attention on ensuring that this most crucial of goals is achieved. However, the combination of silences and misplaced emphases on particular areas creates an overall approach which falls very far short of even envisaging truly inclusive growth. In particular, the Approach Paper fails to address or wrongly deals with five critical areas that are not only essential for inclusive growth but also the most burning policy issues of the present time. These areas are control over and loss of land; employment generation; agriculture and food security; health; and education.

The land question

For a while now, issues relating to land control and assets distribution had gone out of fashion in policy discussion. However, they were always critical in affecting ground realities, and now the issues involved are so pressing that they simply cannot be wished away and must be addressed directly by the state at different levels. It is not simply that the pattern of landownership and control has been concentrated and subject to a significant degree of gender discrimination. It is also that recent patterns of development have created much more dispossession and dislocation, especially among the peasantry and forest dwellers, and this has created not only much more material distress but also widespread social tension.

The NSS data on landholdings, as expressed in the data collected in the 59th Round of the survey and shown in Chart 1, indicate a significant increase in landlessness among rural households. According to these data, the proportion of landless rural households had been broadly stable for three decades from the early 1970s at around 28 per cent, and had come down to 22 per cent in 1991-92. But the data relating to 2002-03 indicate a very sharp increase to nearly one-third of rural households. A similar (and even more accentuated) increase had been evident from the NSS employment survey, which suggested that well above one-third of rural households had no land in 1999-2000.

This growing landlessness is not fortuitous: it is the result of a process that has been marked in the countryside over the last decade, of reduced economic viability of cultivation, that has particularly squeezed small producers. This is discussed in more detail below, but the moot point in this context is that financial stress, including the inability to repay loans taken for cultivation and for other purposes, has forced many farmers to sell their lands and join the landless population. This process is likely to have been especially strong among farmers with marginal holdings, which may explain why their proportion has fallen slightly in the most recent period.

In addition, the economic growth process has involved increasing displacement of people from their land, with inadequate or no compensation and rehabilitation measures. Such displacement has resulted not only from large irrigation projects but also for urban expansion, increases in transport networks such as roads and railways, and the like. Tribal populations have been disproportionately affected by this. The inadequacy of current rehabilitation practices, and the possibilities for social discord, have been recognised in the Approach Paper. But more needs to be done than simply ''frame a transparent set of policy rules'', and the Planning Commission should really have used this opportunity to reconsider the strategy of growth so as to ensure that displacement and dispossession are themselves minimised as far as possible. Instead, the Approach actually calls for dilution or removal of urban land ceiling acts by the state governments, thus reinforcing land monopolies of a few large players.

Despite these pressing and increasingly urgent concerns, discussion of land reforms - which are once again a topical issue - finds no place in the document. Nor is there any concern about the problem of recognising the land rights of women, and ensuring that women be given pattas in the event of any redistribution or rehabilitation.

Employment generation

Despite all evidence to the contrary - most obviously from the direct experience of the past and current Plan periods - the Planning Commission adopts a trickle-down approach whereby it is assumed that output growth will automatically generate more employment, and that too in sufficient quantities to meet the growing labour force. Yet it is obvious to all that the major failure of the growth process, and the most important impediment to ''inclusive'' growth, is the lack of adequate employment generation.

Recent NSS data, described in Chart 2, show a very sharp increase in open unemployment rates for men and women in both rural and urban areas, despite this being the period of highest recorded rates of aggregate output growth. In a country where there is no unemployment benefit and no social protection for those without jobs, and where most of the poor have no option but to find some work simply to survive, such an increase in open unemployment is remarkable and historically unprecedented. It points to a huge absence of productive income opportunities across both urban and rural areas. And it shows very clearly that ''trickle down'' cannot be relied upon to generate jobs.

Yet the discussion on employment generation is probably the weakest section of the Approach Paper, whereas it should have received the central focus. It is not listed at the start as among the most important challenges, and casual attitude permeates the rest of the document. There is no serious consideration of how to ensure that the growth process will actually create more jobs. Even worse, policies that will actually operate to reduce employment are strewn throughout the paper.

There is apparently a belief that labour market flexibility, which is a euphemism for reduced protection to workers in the organised sector, will automatically ensure more employment creation, even though more than 90 per cent of Indian workers currently have no protection at all, and there is little international or domestic experience to justify this hackneyed argument. Even while the Planning Commission effectively wants to remove protection from workers in the unorganised sector, there appears to be a general lack of concern with the fate of unprotected workers generally. Thus, it is surprising that the Approach makes no mention at all of an extremely important new initiative of providing social security to informal sector workers, that has been proposed by the National Commission on the Unorganised Sector in its recently released report.

The agrarian crisis and food security

The persistent crisis in agriculture is well known; indeed, the UPA government recognised it and insisted that greater policy focus on agriculture would form one of the basic elements of its economic strategy. More recently, the continuing and even increasing incidence of farmersí suicides in some particularly affected regions has prompted the announcements of specific relief ''packages'' which may have more cosmetic than real effects.

Nevertheless, the causes of the current agrarian distress are now widely recognised. The combination of continuously higher input prices and volatile output prices, along with reduced access to institutional credit and inadequate public attention to the problems of dryland farming, have created problems for all farmers, but obviously the smaller and financially weaker sections of the peasantry have been the worst affected. Even the measure that are necessary to deal with this are now known to state and central governments. In fact, the National Commission on Farmers headed by M. S. Swaminathan has made a series of important recommendations, both general and specific and long term as well as short term, to address this current crisis.

In this context, the very least that could be expected of the Planning Commission was that this context and the specific measures already available for discussion would be taken on board in the Approach Paper. Unfortunately, this does not seem to be the case. In fact, the discussion suggests that the important reports of the Farmersí Commission have not even been read carefully! The problems of agriculture are dealt with simplistically, based on the assumption that encouraging corporate farming and diversification into horticulture will be enough to make agriculture viable and buoyant again. The basic problems facing most farmers in the country, especially small peasants, are not addressed at all: rising prices of inputs and very volatile output prices; problems of access to assured water supply and difficulties of raising cash crops on dryland areas; the inadequate support to related activities such as livestock rearing; poor extension services which do not provide the latest or relevant information to farmers; the exclusion of the vast majority of petty cultivators such as tenant and women farmers, from the ambit of institutional credit; the inadequate protection provided by crop insurance schemes, and so on.

In addition to this, the real and growing problem of food insecurity has not received any attention at all. The dominant public perception is of major and disturbing changes in the food economy of India, given the recent need to import food grains, pulses and sugar for the first time in thirty years, as part of the measures to stem the steep rise in prices of essential commodities, as well as the evidence of growing hunger and even starvation reports from certain areas. The public distribution system has been run down and does not provide adequate access to the poor: it urgently needs expansion to be made universal. The expansion of the ICDS scheme and its nutrition component similarly is something that has even been mandated by the Supreme Court, although thus far the central government has not fulfilled its legal obligations in this matter. So the current context is one in which food security - both on the ground and at the macro level - should surely have been a priority among our planners. Surely, the Planning Commissioní s silence on this matter is deafening.

Health and education

These were declared to be the central concerns of the UPA government, and are associated with flagship programmes such as the National Rural Health Mission and progressive legislation such as the Right to Education Bill. yet even in these crucial social sectors, the mindset displayed in the Approach Paper is still very much that which was displayed by the earlier government, of raising user fees and reducing so-called ''subsidies'' in areas which must by publicly funded.

With respect to health provision, the Approach Paper talks of raising user charges, which is bound to exclude most of the poor in what is already a hugely underfunded public provision. In addition, there is an extraordinary suggestion to provide remuneration to public health workers by the service! Surely it is obvious that providing decent public services requires adequate numbers of decently paid personnel, without which the services are likely to be substandard. In a matter as crucial as health, linking pay to ''productivity'' or ''delivery'' however defined will not only militate against such workers, it will also create incentives of the most undesirable kind with unwanted social consequences.

Similarly, there is an argument for higher fees in higher education, despite the well known problems of social exclusion that can result from this and the presence of significant externalities that make higher education also clearly a merit good. Another problematic proposal relates developing a voucher system, which has been proposed not only for secondary and higher education but even for primary education. According to such a scheme, children would be provided with vouchers with which they could pay fees in private schools as well as public schools, thereby ''enlarging choice''. This idea, which comes from a failed US experience, completely ignores the stark realities of the government school system at present, which is desperately underfunded. Official estimates suggest that around one-fifth of schools do not have a building at all, and another one-fourth have only one room. More than 15 per cent of elementary schools function with only one teacher and another 20 per cent one fifth with only two teachers for five classes. In this appalling context, surely the priority in expenditure must be to provide more infrastructure, teachers etc. in public schooling, without which no quality improvements there are possible, and not to indirectly subsidise private schools.

There are numerous other problems with different suggestions made in the Approach. In general they stem from an underlying perception that creating a profitable environment for private sector functioning will be enough to fulfil most social goals, and no particular planning strategy is required for this. Coming from the organisation charged with handling public expenditure for development, this is a disturbing perspective.

© MACROSCAN 2006