Themes > Features

14.07..2008

IT Firms and Financial Markets: A Changed Relationship

India's

stock market has lost its lustre for those counting their wealth in terms

of the value of the paper assets they hold. Between the end of October

2007 and early June this year, the Sensex has fallen from the 20000 level

to around 15500, or by close to 23 per cent. That decline implies a substantial

loss of paper wealth that hurts most those who bought into the market

at its peak. But not all financial investors need be losers of this magnitude.

What is noteworthy is that if we look at the Bombay Stock Exchange’s Information

Technology Index, the decline in its value between October 29, 2007, when

it recorded its previous high of 4712.5, and 3 June 2008, when it touched

4542.8, was less than 4 per cent.

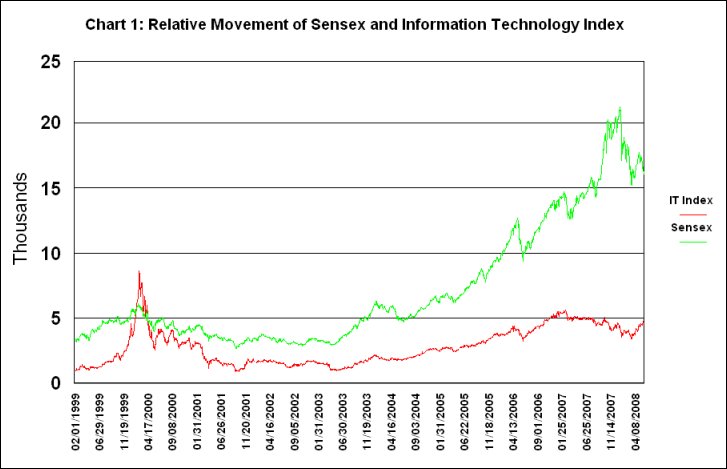

This difference is remarkable indeed, but is partly a result of the fact that the IT sector has only marginally reflected the unprecedented boom that was witnessed in India’s stock markets since 2004. As Chart 1 makes amply clear, when the Sensex was rising rapidly and soaring above the levels it had reached before 2004, the IT index recorded much lower rates of increase and stood way below the peak level of 8613.5 it touched on 21 February 2000. The highest level it touched in the period since 2004 was 5611.3 on 19 February 2007. A consequence of this has been the widening distance between the graphs reflecting movements in the Sensex and the Information Technology Index.

Thus, the experience during 2004 to 2008 was the opposite of that witnessed during the stock boom at the turn of the millennium, when the stocks of IT companies induced a degree of buoyancy into the market, with the rise in the Information Technology Index proving to be much higher than that of the Sensex. During those years, IT companies came to dominate the market. This comes through from the following quote from a report in this paper in its issue dated 2 January, 2000:

One mistaken conclusion that was derived from this trend was that the rapid growth and the immense promise of the IT sector had made it one where share values have come to reflect the true worth of companies. This in turn was seen as paving the way for the "ownership economy" where what an individual owned rather than what she earned was the right indicator of success. By way of evidence, reference was repeatedly made to the early adoption by the information technology industry, led by Infosys, of employee stock options (ESOPs). One journalist writing on Infosys at the end of 1999 (India Today, 8 November, 1999) waxed eloquent thus: "Of the 4,782 employees, lovingly addressed as "Infoscions", 1,667 now hold ESOPs. Of them, 1,376 have stock valued at over Rs 10 lakh each. Among them, the total number of the jeans-clad "crorepatis" is a staggering 412. And 97 of them have left the Rs. 1 crore milestone far behind, having become dollar millionaires (Rs 4.3 crore-plus) by age 30-35. No other company in India, not even Infosys' software rivals Wipro Ltd and Satyam Computers, has shared its wealth with such a large number of employees."

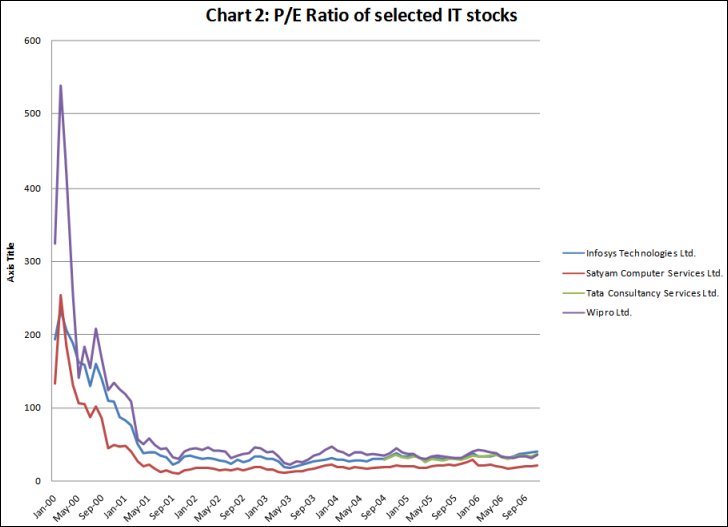

There were a number of features of the IT industry's romance with the stockmarket that was missed in this type of analysis. The first was that stock prices were at levels not warranted by fundamentals. As Chart 2 shows, at the peak of the boom price earnings ratios of the most successful IT companies were clearly at levels that indicated that these stocks were overpriced, possibly because they had been chosen by speculators who were in essence manipulating markets. Not surprisingly that boom did not last. What is more since then price earnings ratios have been, even when high, within ranges that do not reflect "irrational exuberance".

There were other such stories, even if they were less dramatic than this example of a move from a position of relatively puny wealth by international standards into the ranks of the world's wealthiest. This easy movement to the apex of the wealth pyramid added one more cause for celebrating India’s IT success. What was disconcerting was that market capitalisation, or the value of a company computed on the basis of the price at which individual shares of the company trade in the market, was increasingly replacing real asset values as the principal indicator of company size and worth. The top 50 or 500 are now determined by many analysts not on the basis of asset value but market valuation. This is part of a larger disease which assesses the size (and ostensibly, therefore, maturity) of India's stock market based on total market capitalisation.

The consequence was a picture of dramatic change. In 1990, before the reforms began, total market capitalisation in the Bombay Stock Exchange (BSE) was less than Rs. 100,000 crore - a level that the market capitalisation of Wipro alone crossed in early 2000. Aggregate market capitalisation in the BSE reflected an average increase of 100 per cent a year during the 1990s. This was not only taken as suggesting a dramatic rise to maturity of the stock market, but as reflecting economic buoyancy, even though it conveyed a completely different picture than that provided by GDP growth, which averaged around 6 per cent compound a year.

The problem with this market hardly needs emphasizing. To start with, market values of individual shares are not a reflection of the true worth of the companies involved, but the state of demand for those shares relative to their supply. Demand, at the margin, was clearly being driven by foreign institutional investors in search of diverse portfolios, who then numbered more than 500 in the country. During the first 18 trading sessions in February 2000, the FIIs invested more than Rs. 2660 crore, which was more than half the annual average investment that occurred during the years since 1993, when FII investment in India's stock markets was first allowed. The inflow during those days was in fact higher than the inflow during the last six months of 1999. Clearly, there had then been a sudden surge of interest in India.

With hindsight, three factors appear to explain this trend. First, a speculative boom in IT stocks in general and internet stocks in particular in American markets. Second, the fact that among emerging markets India was a country with a growing IT presence, in US markets, strengthened by strategic alliances with leading US firms. Finally, the fact that those Indian firms that had gone in for a NASDAQ listing in American markets were at that time performing quite well, encouraging other Indian firms in the IT and entertainment sectors to contemplate a similar strategy.

These factors had ensured that the speculative fever in IT and related stocks in American markets had spilt over into the Indian market. For example, the bull run in Wipro shares came in the wake of two major strategic alliances it had forged with Microsoft, the software giant, and Symbian, the combination of leading players that were targeting the emerging market for wireless devices that link to the internet.

While demand for Indian equity in selected sectors was spurred by these factors, the supply of such shares was (and is) limited for two reasons: first, internationally acceptable players were still small in number, even if increasing over time; and, second, the number of shares from such enterprises that was available in the market was limited. As mentioned earlier, only 25 per cent of Wipro shares were with the "public" as opposed to the promoter, and most of those holding such shares were unlikely to be ready to part with them in the course of a boom. The net result is that the demand-supply balance at the margin is heavily weighted in favour of sellers, resulting in astronomical price increases in short periods of time. This is true of other companies as well. Needless to say, if many promoters chose to exploit the situation by off-loading a significant chunk of their holding, the demand-supply balance for shares of individual companies could change substantially, resulting in a fall in prices that is as dramatic as the previous rise.

Despite this dependence of share prices on the limited supply resulting from a high holding by the promoter and their associates, the market capitalisation index applies the price at the margin to value the stock of the company. This results in a dramatic surge in the "market value" of the company along with the price. Not surprisingly, a few firms and sectors accounted for the early-2000 surge in market capitalisation. By mid-February, Wipro alone accounted for 15 per cent of market capitalisation in the BSE and the combined market value of around 150 software companies accounted for 32 per cent. It must be remembered that at the beginning of the 1990s, these companies hardly featured in the BSE.

In short, India's new found wealth was like a pyramid of cards built by a bunch of flighty investors. Small money by world standards was rushing into a few sectors, honing in on a few companies which had a small number of shares on trade. This pushed up prices at the margin to create an illusion of wealth, because the commodity producing sectors, especially agriculture, were languishing. But at the top, things appeared as if they could not have been better.

However, that speculative fever gave way to a sharp fall in stock prices when investors (foreign and domestic) realized that there was nothing which warranted a share to trade at 750 times the annualised per share earnings of a company, as it did in the case of Wipro. Compared to its February 2000 peak of close to Rs. 9000 per share, the Wipro stock closed at Rs. 2282 on October 20, 2000, which was the day after it made its debut at the New York Stock Exchange.

The focus on and dominance of a few shares was explained by another feature of the IT industry. This was the overall concentration of exports and sales in a few domestic firms in the industry. In periods when IT stock prices rose, it is the stock of these companies that soared, converting their promoters into billionaires even for a short period of time. However, the performance of the few other firms that were listed in the stock market was lacklustre. This difference in stock price performance between the leaders and followers has persisted to this day.

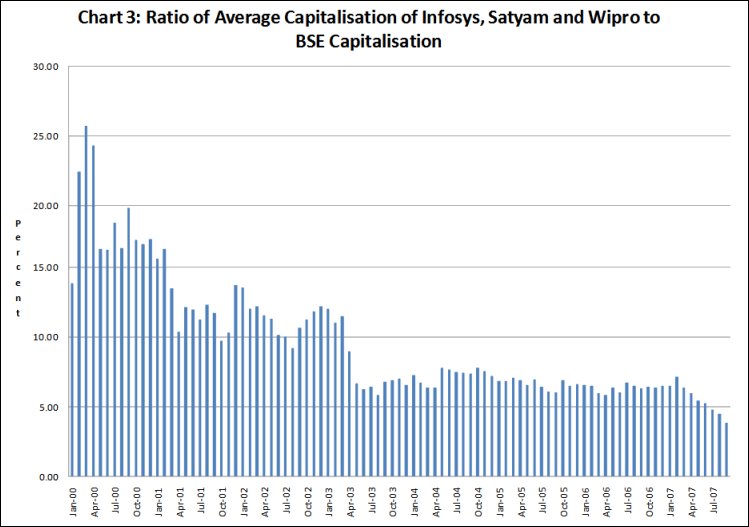

What has changed however is the average relative performance of the sector. Investors having burnt their fingers during India’s version of the dot-com boom and bust at the turn of the millennium have since held back investments in this area. As a result, the maximum level that the IT index touched during the post 2003 period (on 19 February 2007) was 65 per cent below its 2000 peak. The net result is that the IT sector has been losing its importance in the market as a whole. The ratio of the market capitalization of three leading firms for which data is available for a long period to the BSE’s aggregate market capitalization has fallen from more than 25 per cent in March 2000 to less than 4 per cent by October 2007 (Chart 3).

This growing divergence between the market in general and the IT firms within it indicate that after the experience of 1999-2000, investors moved on to other shares, so that the boom since 2004 has been focused on other industries and sectors. But the investors are the same or similar, as evident from the fact that FIIs have played a major role in the post-2003 boom as well. This raises a question that looks for an answer: now that the post-2003 boom in stock markets is reversing itself, where would these investors turn? Commodities and commodity futures may be one answer. If so, those calling for increased regulation of these markets may have a case, because the effects of speculation there adversely affects those who have gained little, if anything, from India’s post 1990 growth.

This difference is remarkable indeed, but is partly a result of the fact that the IT sector has only marginally reflected the unprecedented boom that was witnessed in India’s stock markets since 2004. As Chart 1 makes amply clear, when the Sensex was rising rapidly and soaring above the levels it had reached before 2004, the IT index recorded much lower rates of increase and stood way below the peak level of 8613.5 it touched on 21 February 2000. The highest level it touched in the period since 2004 was 5611.3 on 19 February 2007. A consequence of this has been the widening distance between the graphs reflecting movements in the Sensex and the Information Technology Index.

Thus, the experience during 2004 to 2008 was the opposite of that witnessed during the stock boom at the turn of the millennium, when the stocks of IT companies induced a degree of buoyancy into the market, with the rise in the Information Technology Index proving to be much higher than that of the Sensex. During those years, IT companies came to dominate the market. This comes through from the following quote from a report in this paper in its issue dated 2 January, 2000:

One mistaken conclusion that was derived from this trend was that the rapid growth and the immense promise of the IT sector had made it one where share values have come to reflect the true worth of companies. This in turn was seen as paving the way for the "ownership economy" where what an individual owned rather than what she earned was the right indicator of success. By way of evidence, reference was repeatedly made to the early adoption by the information technology industry, led by Infosys, of employee stock options (ESOPs). One journalist writing on Infosys at the end of 1999 (India Today, 8 November, 1999) waxed eloquent thus: "Of the 4,782 employees, lovingly addressed as "Infoscions", 1,667 now hold ESOPs. Of them, 1,376 have stock valued at over Rs 10 lakh each. Among them, the total number of the jeans-clad "crorepatis" is a staggering 412. And 97 of them have left the Rs. 1 crore milestone far behind, having become dollar millionaires (Rs 4.3 crore-plus) by age 30-35. No other company in India, not even Infosys' software rivals Wipro Ltd and Satyam Computers, has shared its wealth with such a large number of employees."

There were a number of features of the IT industry's romance with the stockmarket that was missed in this type of analysis. The first was that stock prices were at levels not warranted by fundamentals. As Chart 2 shows, at the peak of the boom price earnings ratios of the most successful IT companies were clearly at levels that indicated that these stocks were overpriced, possibly because they had been chosen by speculators who were in essence manipulating markets. Not surprisingly that boom did not last. What is more since then price earnings ratios have been, even when high, within ranges that do not reflect "irrational exuberance".

There were other such stories, even if they were less dramatic than this example of a move from a position of relatively puny wealth by international standards into the ranks of the world's wealthiest. This easy movement to the apex of the wealth pyramid added one more cause for celebrating India’s IT success. What was disconcerting was that market capitalisation, or the value of a company computed on the basis of the price at which individual shares of the company trade in the market, was increasingly replacing real asset values as the principal indicator of company size and worth. The top 50 or 500 are now determined by many analysts not on the basis of asset value but market valuation. This is part of a larger disease which assesses the size (and ostensibly, therefore, maturity) of India's stock market based on total market capitalisation.

The consequence was a picture of dramatic change. In 1990, before the reforms began, total market capitalisation in the Bombay Stock Exchange (BSE) was less than Rs. 100,000 crore - a level that the market capitalisation of Wipro alone crossed in early 2000. Aggregate market capitalisation in the BSE reflected an average increase of 100 per cent a year during the 1990s. This was not only taken as suggesting a dramatic rise to maturity of the stock market, but as reflecting economic buoyancy, even though it conveyed a completely different picture than that provided by GDP growth, which averaged around 6 per cent compound a year.

The problem with this market hardly needs emphasizing. To start with, market values of individual shares are not a reflection of the true worth of the companies involved, but the state of demand for those shares relative to their supply. Demand, at the margin, was clearly being driven by foreign institutional investors in search of diverse portfolios, who then numbered more than 500 in the country. During the first 18 trading sessions in February 2000, the FIIs invested more than Rs. 2660 crore, which was more than half the annual average investment that occurred during the years since 1993, when FII investment in India's stock markets was first allowed. The inflow during those days was in fact higher than the inflow during the last six months of 1999. Clearly, there had then been a sudden surge of interest in India.

With hindsight, three factors appear to explain this trend. First, a speculative boom in IT stocks in general and internet stocks in particular in American markets. Second, the fact that among emerging markets India was a country with a growing IT presence, in US markets, strengthened by strategic alliances with leading US firms. Finally, the fact that those Indian firms that had gone in for a NASDAQ listing in American markets were at that time performing quite well, encouraging other Indian firms in the IT and entertainment sectors to contemplate a similar strategy.

These factors had ensured that the speculative fever in IT and related stocks in American markets had spilt over into the Indian market. For example, the bull run in Wipro shares came in the wake of two major strategic alliances it had forged with Microsoft, the software giant, and Symbian, the combination of leading players that were targeting the emerging market for wireless devices that link to the internet.

While demand for Indian equity in selected sectors was spurred by these factors, the supply of such shares was (and is) limited for two reasons: first, internationally acceptable players were still small in number, even if increasing over time; and, second, the number of shares from such enterprises that was available in the market was limited. As mentioned earlier, only 25 per cent of Wipro shares were with the "public" as opposed to the promoter, and most of those holding such shares were unlikely to be ready to part with them in the course of a boom. The net result is that the demand-supply balance at the margin is heavily weighted in favour of sellers, resulting in astronomical price increases in short periods of time. This is true of other companies as well. Needless to say, if many promoters chose to exploit the situation by off-loading a significant chunk of their holding, the demand-supply balance for shares of individual companies could change substantially, resulting in a fall in prices that is as dramatic as the previous rise.

Despite this dependence of share prices on the limited supply resulting from a high holding by the promoter and their associates, the market capitalisation index applies the price at the margin to value the stock of the company. This results in a dramatic surge in the "market value" of the company along with the price. Not surprisingly, a few firms and sectors accounted for the early-2000 surge in market capitalisation. By mid-February, Wipro alone accounted for 15 per cent of market capitalisation in the BSE and the combined market value of around 150 software companies accounted for 32 per cent. It must be remembered that at the beginning of the 1990s, these companies hardly featured in the BSE.

In short, India's new found wealth was like a pyramid of cards built by a bunch of flighty investors. Small money by world standards was rushing into a few sectors, honing in on a few companies which had a small number of shares on trade. This pushed up prices at the margin to create an illusion of wealth, because the commodity producing sectors, especially agriculture, were languishing. But at the top, things appeared as if they could not have been better.

However, that speculative fever gave way to a sharp fall in stock prices when investors (foreign and domestic) realized that there was nothing which warranted a share to trade at 750 times the annualised per share earnings of a company, as it did in the case of Wipro. Compared to its February 2000 peak of close to Rs. 9000 per share, the Wipro stock closed at Rs. 2282 on October 20, 2000, which was the day after it made its debut at the New York Stock Exchange.

The focus on and dominance of a few shares was explained by another feature of the IT industry. This was the overall concentration of exports and sales in a few domestic firms in the industry. In periods when IT stock prices rose, it is the stock of these companies that soared, converting their promoters into billionaires even for a short period of time. However, the performance of the few other firms that were listed in the stock market was lacklustre. This difference in stock price performance between the leaders and followers has persisted to this day.

What has changed however is the average relative performance of the sector. Investors having burnt their fingers during India’s version of the dot-com boom and bust at the turn of the millennium have since held back investments in this area. As a result, the maximum level that the IT index touched during the post 2003 period (on 19 February 2007) was 65 per cent below its 2000 peak. The net result is that the IT sector has been losing its importance in the market as a whole. The ratio of the market capitalization of three leading firms for which data is available for a long period to the BSE’s aggregate market capitalization has fallen from more than 25 per cent in March 2000 to less than 4 per cent by October 2007 (Chart 3).

This growing divergence between the market in general and the IT firms within it indicate that after the experience of 1999-2000, investors moved on to other shares, so that the boom since 2004 has been focused on other industries and sectors. But the investors are the same or similar, as evident from the fact that FIIs have played a major role in the post-2003 boom as well. This raises a question that looks for an answer: now that the post-2003 boom in stock markets is reversing itself, where would these investors turn? Commodities and commodity futures may be one answer. If so, those calling for increased regulation of these markets may have a case, because the effects of speculation there adversely affects those who have gained little, if anything, from India’s post 1990 growth.

©

MACROSCAN 2008