Themes > Features

28.07.2009

Global Trade in a Time of Crisis

With

the world well into the second year of a recession whose intensity is

unprecedented in the period since the Second World War, two questions

are receiving considerable attention. The first, of course, is whether

the evidence of a decline in the rate of contraction of output and rate

of increase in unemployment in the US, the G7 and elsewhere in the world

is a sign that the recession has touched bottom. The second is whether

there is evidence of a degree of desynchronization of the incidence

and intensity of the crisis across countries. The latter, it is argued,

would help some countries serve as shock-absorbers by reducing the intensity

of the crisis as well as endow the system with sources of growth that

could ensure recovery once the recession has bottomed out. China and

India are two countries that are often referred to in this context.

The case for desynchronization is difficult to make in a globalised

and more integrated world for three reasons. First, globalisation implies

that integration of economies through trade is substantially more than

it used to be so that a downturn in one part of the globe would quickly

transmit itself to other regions and countries. Second, globalisation

results in the creation of multi-country production platforms for various

final goods. This creates international production chains, so that an

increasing share of trade is not the cross-border movement of products

from different industries and activities or even of dissimilar products

from technologically similar industries. Rather a significant part of

trade is intra-industry and involves the movement across borders of

semi-finished products at different stages of processing. When a recession

hits any particular industry and reduces the volume of trade in that

area, the derived demands for the inputs at different stages of the

production chain fall, spreading the effects of the recession globally.

Finally, trade liberalisation has removed quantitative restrictions

and reduced import duties across-the-board in most countries. Depending

on the extent of trade liberalization the relative importance of the

domestic market in driving growth has declined to different degrees

in different countries. This implies that unless countries alter the

degree of protection they resort to, using the domestic market as a

foil against the effects of a decline in trade is difficult to ensure.

And opting for protection at a time of crisis would only invite retaliatory

action from trade partners.

These features of trade in a globalised world imply that desynchronization

leading to some countries serving as shock absorbers and even sources

of stimuli for growth depends on the degree of globalization and liberalization

itself. This in turn implies that assessments of the extent of desynchronization

cannot rely merely on evidence on the differential distribution of the

slowdown in GDP growth or increase in unemployment, but must examine

changes in the rate of growth and pattern of world trade as well.

Trade data at a global level is released with a lag when compared with

data on GDP and in the case of some countries even when compared with

employment and unemployment data. Not surprisingly, it was only in July

that the data on international trade trends during the first quarter

of 2009 in the G7 countries and the world economy was released by the

OECD Secretariat and the World Trade Organization respectively. To recall,

while the slump in production in the developed countries has been with

us since the end of 2007, it was in the last quarter of 2008 and the

first quarter of 2009 that the crisis was most intense. And whatever

evidence we have about the crisis moderating and even possibly bottoming

out comes from the second quarter of the year. So the most recent evidence

on international trade trends relates to the period when the recession

was possibly in its most intensive phase.

As the WTO's World Trade Report 2009 notes: ''Signs of a sharp deterioration

in the global economy were evident in the second half of 2008 and the

first few months of 2009 as world trade flows sagged and production

slumped, first in developed economies and then in developing countries.

Although world trade grew by 2 per cent in volume terms over the course

of 2008, it tapered off in the last six months of the year and was well

down on the 6 per cent volume increase posted in 2007.'' The most important

trend the evidence points to is the sharp contraction in imports into

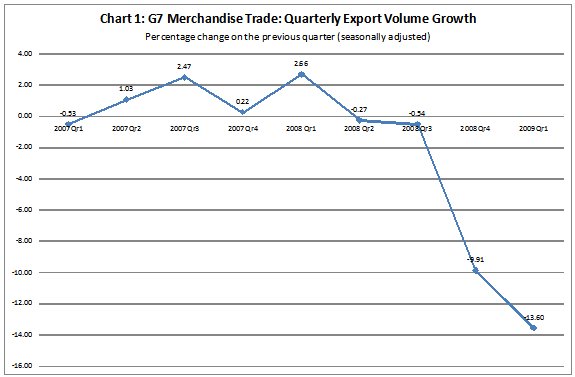

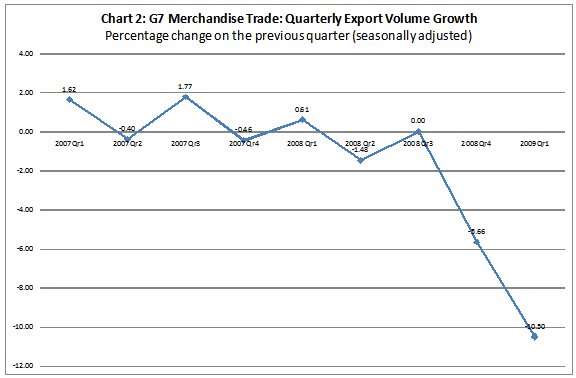

(and, of course, exports from) the G7 countries (Charts 1 and 2). The

decline in import growth relative to the previous quarter which was

close to 6 per cent in the last quarter of 2008, jumped to 10.5 per

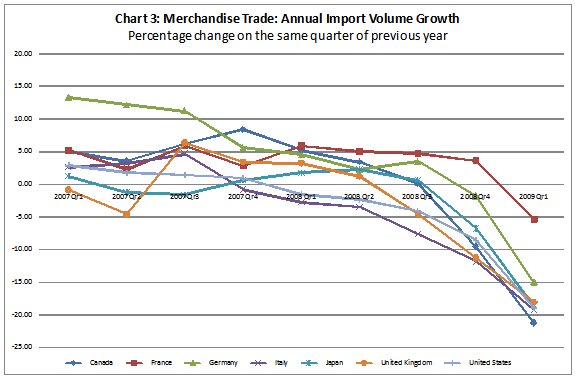

cent in the first quarter of 2009. This trend seems to be generalised

across the G7 (Chart 3).

The

contraction in import growth on a year on year basis was even sharper.

The quarter-on-previous-quarter and year-on-year rates of growth of

imports stood at -9.5 and -23.3 per cent for Germany and -11.8 and -19

per cent in the case of the US. With the G7 countries accounting for

40 per cent of global merchandise imports this must have had a severe

contractionary impact on global economic activity.

The slowdown was not restricted to merchandise trade alone. Compared

with the previous quarter, the value of imports of goods and services

into OECD countries, measured in seasonally adjusted current price US

dollars, dropped significantly in the first quarter of 2009, even if

less sharply then the volume of goods imports. The figure fell by 15.2%.

On a year-on-year basis, the value of imports of goods and services

declined by 27.9%. Thus the sharp drop observed in Q4 2008 continued

in Q1 2009, though in both comparisons, goods fell much more sharply

at about twice the rates than those of services.

The effects of this slowdown on countries like China were visible in

2008 itself. China's merchandise exports in constant prices which grew

by 22 and 19.5 per cent respectively in 2006 and 2007 collapsed to 2.5

per cent. Interestingly the impact on India—a country much less dependent

on merchandise exports for growth—was far less dramatic, with the growth

rates standing at 11, 13 and 7 per cent respectively.

The impact on China's exports was particularly sharp in certain product

categories. Exports of office and telecom equipment fell by 7 per cent

in the fourth quarter of 2008, as compared with the same period of the

previous year. This occurred despite the fact that these exports grew

at an average rate of 17 per cent during the first three quarters of

2008. According to the WTO, exports of this category of items to the

United States ''fell even more sharply, registering a 13 per cent decline

in the fourth quarter (of 2008) after growth of 10 per cent in the third

quarter. Overall, exports of Chinese manufactured goods to the United

States increased just 1 per cent over the previous year, after growth

of 14 per cent in the third quarter.''

This

is significant given the role of this product group in the hi-tech manufacturing

sector in China. In the mid-1980s the hi-tech sector was completely

dominated by the Radio, television and communications equipment sub-sector,

which accounted for almost two-thirds of all hi-tech manufacturing value

added. Since then the production of Office and computing machinery has

been rising rapidly so that by 2005 it accounted for 39 per cent of

hi-tech value added, while that of Radio, television and communications

equipment had fallen to 43 per cent. In sum, information technology

hardware is central to China's hi-tech export success and an important

contributor to incremental manufacturing GDP.

India's production and export structure is different. In part India's

ostensible resilience in the face of the global crisis, reflected in

a much smaller proportionate decline in its GDP in 2008 (1.4 percentage

points on 9.3 percent) relative to China (2.9 percentage points on 11.9

per cent), appears to be because of its much smaller export dependence

on manufacturing. In recent years, India's export dependence has been

much more in knowledge intensive services than manufacturing. But this

per se does not make the country immune to the effects of the global

downturn. World imports of commercial services recorded an increase

in annual growth rates from 12 per cent in 2006 to 18 per cent in 2007,

only to see a decline in that rate to 11 per cent in 2009. And India's

principal market the United States recorded a decline in the rate of

growth of imports of commercial services from 12 per cent in 2006 to

9 per cent in 2007 and further to 7 per cent in 2006. Moreover, India's

interest is in the trade in commercial services (as opposed to transport

and travel services) and here the rates of growth in these three years

were 16, 22 and 10 per cent respectively. That is even the global trade

in services is sharply slowing down in areas in which India has an interest.

Yet this is better than the absolute contraction in the volume of merchandise

imports.

The real point is that exports in general and therefore the exports

of services constitutes a much smaller proportion of GDP in India then

merchandise exports constitute in China's GDP. Hence, it is not India's

less damaging performance in the export area that would count, but the

performance of the domestic market and domestic demand.

Seen in this light, the argument that even if the G7 economies, especially

the US, continue to bounce along the bottom, the global economy can

record a significant recovery because of a return to high growth in

China and India does not seem to have much basis. This would require

in the first instance a sharp shift in China from growth dependent on

external markets to growth dependent on domestic consumption. Secondly,

mechanisms must exist in both China and India for a return to high growth

based on domestic demand, without spurring inflation. And, third this

process must be accompanied by an increase in imports into these countries

from the rest of the world, without destabilizing movements in the balance

of payments and in currency markets, especially in the case of India.

If this combination of factors does not play out, there is unlikely to be a return to high growth in these two large economies, which could help lift the global economy without aggravating preexisting global imbalances. On the other hand, if there is any revival of growth in these economies because of a leakage of the demand generated by the state-financed stimulus being experimented with in the US, UK and elsewhere in the G7, imbalances both in terms of the global distribution of growth and the global balance of payments would only intensify. This would intensify current demands for a dose of protectionism. Not surprisingly, the World Trade Report from the WTO has among its focal themes, ''the challenge of ensuring that the channels of trade remain open in the face of economic adversity.'' This, in its view, requires the design of ''well-balanced contingency measures'' to deal with a variety of unanticipated market situations, with ''the right balance between flexibility and commitments'' in trade agreements. ''If contingency measures are too easy to use, the agreement will lack credibility. If they are too hard to use, the agreement may prove unstable as governments soften their resolve to abide by commitments.'' But the current conjuncture seems to be one where such balance would be near impossible to achieve.

©

MACROSCAN 2009