Themes > Features

26.07.2011

Deciphering Employment Trends*

Since

the release of the Key Indicators from the National Sample Survey Organisation's

(NSSO's) employment survey relating to 2009-10, attention has been focused

on just a few features of those estimates. The most important among

them noted and discussed in the previous article (''The Latest Employment

Trends from the NSSO'') under Features of Macroscan, is the significant

deceleration of the rate of growth of aggregate employment.

However,

government spokespersons have been quick to play down the significance

of those numbers by referring to two other aspects of the NSS 2009-10

figures. The first is the fact that part of the deceleration in workforce

expansion is the result of the substantially larger number of young

people opting to educate themselves.

If we focus on the 15-24 age group, which is the one that is most likely

to choose between education and work, we find that the increase in the

number of those reporting themselves as occupied with obtaining an education

was much higher over the five years ending 2009-10 (16.7 million in

the case of males and 11.9 million in the case of females) than was

true over the previous five years (5.6 and 5.2 million respectively).

This huge difference, which is a positive development from the point

of view of generating a better and more skilled workforce, would have

substantially reduced the number entering the labour force, contributing

to the deceleration in the growth of the total number of workers.

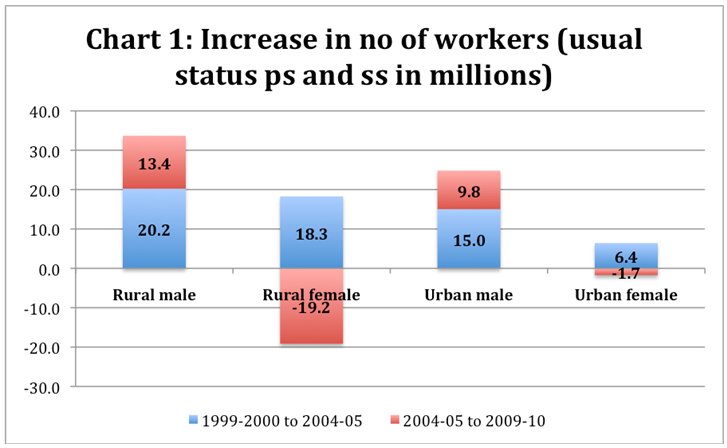

However, the aggregate numbers of principal and subsidiary status workers

suggest that this alone would be inadequate to provide a satisfactory

explanation of what seems to be a dramatic collapse of employment. The

total number of usual status (principal and subsidiary) workers, which

increased by 60 million during the five years ending 2004-05, rose by

just 2.3 million over the subsequent five years (Chart 1). (If we restrict

the comparison to just changes in principal status workers the difference

is still substantial though less dramatic, standing at 48.3 and 13.1

million respectively).

This too has been discounted by pointing to the fact that the fall in

employment increments over the two periods under comparison has been

substantially due to a fall in female employment. Rural female employment,

which rose by 18.3 million between 1999-2000 and 2004-05, registered

a decline of 19.2 million during 2004-05 and 2009-10. Even in the urban

areas, the figures for changes in female employment during the two periods

were significantly different at a positive 6.4 million and a negative

1.7 million respectively. This has been cited as evidence of a definite

underestimation of female employment.

The figures have provided the basis for the criticism from within the

government that the NSSO's 2009-10 survey has significantly underestimated

female employment, which is difficult to capture, especially in rural

areas. It is difficult indeed to believe that this deficiency affected

only the 2009-10 survey, especially to the extent needed to explain

the dramatic difference in changes.

Moreover, if we stick to usual status (principal and subsidiary status)

employment, the change in male employment also points to significant

deceleration. Between 1999-2000 and 2004-05 male employment increased

by 20.2 million in rural areas, while between 2004-05 and 2009-10 it

rose by only 13.4 million. The corresponding figures for the urban areas

were 15 million and 9.8 million respectively. In the case of only principal

status workers, the increases had fallen from 19.2 to 13.6 million in

rural areas and from 14.4 to 10.3 million in urban areas.

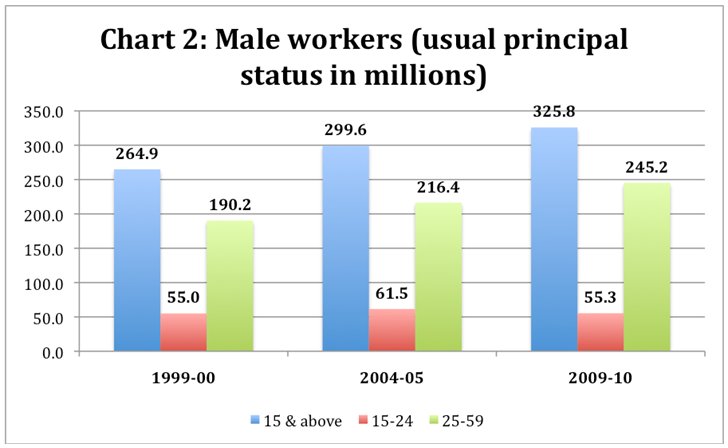

As noted earlier, this decline in employment is partly explained by

the sharp increase in those pursuing an education in the 15-24 age group.

We, therefore, turn to an examination of the trends in employment in

the two main working age groups: 15-24 and 25-59. Let us initially restrict

the analysis to trends in usual principal status employment for males,

to accommodate for what may be the partially correct criticism that

female employment was underestimated to a greater degree in 2009-10

than before.

One positive signal here is that male employment in the 25-59 age group

rose when that in the (education-opting) 15 to 24 age group fell. Male

employment (rural and urban) in the 15-24 age group fell by 6.2 million

between 2004-05 and 2009-10 as compared to an increase of 6.5 million

during 1999-2000 and 2004-05. Contrary to this, the figures for the

changes in the 25-59 age group were 28.8 and 26.2 million respectively

(Chart 2). That is, there was a larger absolute increase in 25-59 age

group employment in the more recent period when compared with the previous

one. However, the difference here too is small and the rate is marginally

lower (13.3 as opposed to 13.8 per cent) given the rising base value.

In the case of females, however, even in this age group employment fell

during the recent period by 5.1 million, while it had increased by a

huge 13.1 million during the previous period. Thus, even if we restrict

ourselves to the most favourable category in aggregate principal status

employment in the case of males, which is the 25-59 age group, the most

we can say is that employment growth has not been lower during the five

years ending 2009-10, as compared to the previous period. This is despite

the fact that these were the years when there was a substantial acceleration

of GDP growth from the 6-7 per cent range to the 8-9 per cent range

between these two periods.

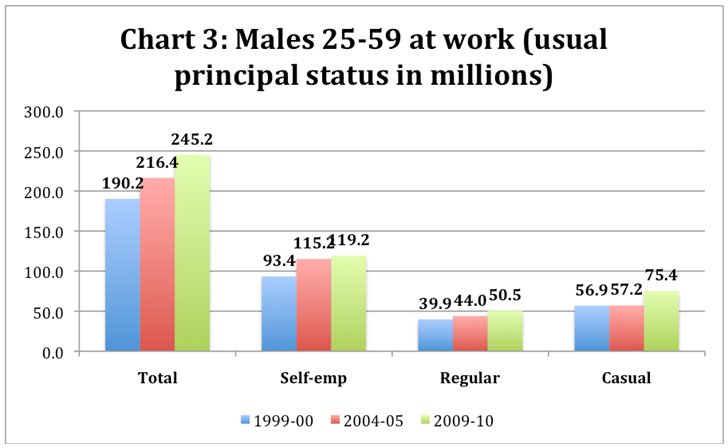

There

seems to be a second positive that emerges on first examination of the

data relating to male, 25-59 age group employment, which is that much

of the increase in employment is paid employment as opposed to self-employment.

This points to a structural shift in employment generation since most

of the additional male employment generated in this age group during

the 1999-2000 to 2004-05 period was in the self-employment category

(Chart 3).

Self-employment rose by 21.8 million during that period, as compared

with just 4 million during the more recent period. On the other hand,

during 2004-05 to 2009-10, paid (regular or casual) employment increased

by 24.6 million, as compared with just 4.4 million during the previous

period. Given the fact that self-employment could be substantially distress-driven,

this is indeed welcome.

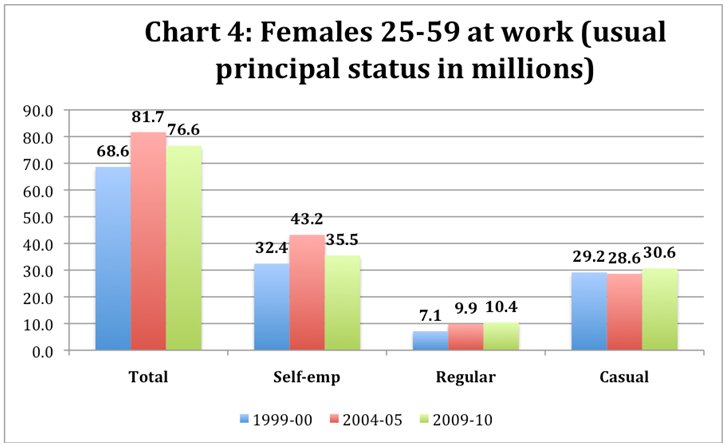

But that assessment needs to be moderated on three counts. First, the

structural shift in the nature of additional employment occurs in a

period when aggregate employment even among 25-59 years-old males has

not been rising any faster. Second, around two-thirds of the increase

in paid employment in the recent period is in the casual work category,

which is likely to be less well-paid and volatile, leading to much lower

earnings. Third, if we consider female employment in the 25 to 59 age

group, while there has been a decline of 7.7 million in the number of

self-employed workers, the number of paid workers rose by just 2.6 million

(Chart 4). The increase in paid employment here has been far short of

the loss of self-employment.

These

features have to be seen in the context of certain changes observed

in the sectoral composition of the expansion of employment during the

two periods. Though there has been a change in industrial classification

adopted in the most recent survey, the National Industrial Classification

(NIC) 2004, we can assume that its impact would not be substantial at

the level of broad categories.

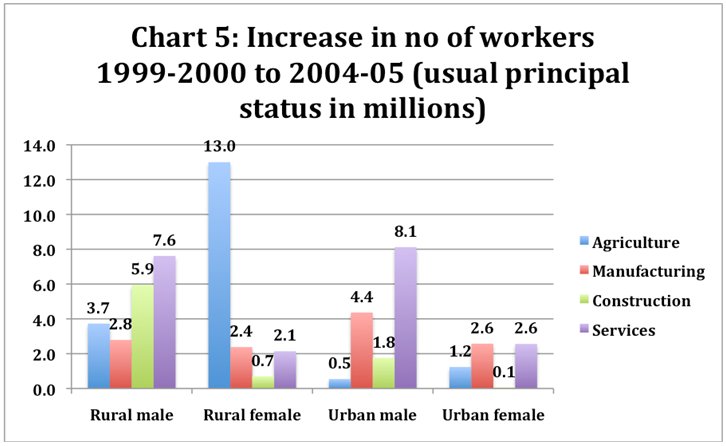

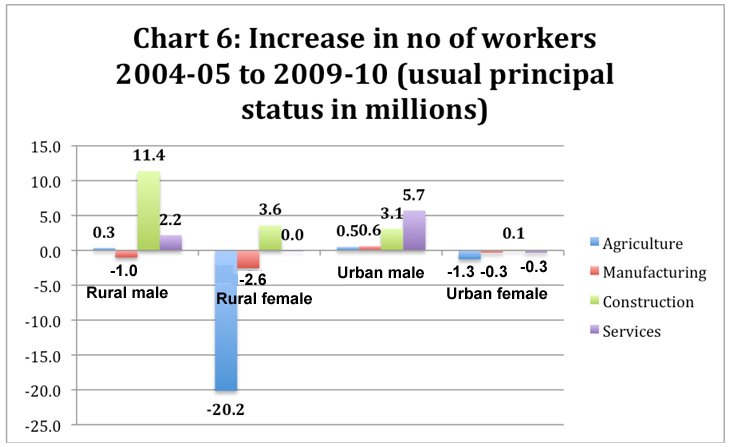

The figures show that over 1999-2000 to 2004-05, the increase in employment

was distributed across agriculture, manufacturing construction and services,

though services and construction dominated in the case of males and

agriculture in the case of rural females. As compared to this, during

the 2004-05 to 2009-10 period, agriculture and manufacturing made negative

or negligible contributions to the increase in employment, whereas construction

played the dominant role in the case of both males and females (Chart

5 and 6). Clearly even the small contributions made by the commodity

producing sectors to employment increases are disappearing, making the

system dependent on construction and services, especially the former.

In sum, even among sections of the population who would not and have

not been opting for education as activity and for whom the identification

of work participation may not be difficult, the main source of employment

during the high growth years seems to be casual work in the construction

sector. This is likely to be among the more volatile among employment

categories, with lower wages, higher uncertainty of employment and,

therefore, limited earnings potential. So even if we take account of

the increased participation of the young in education and the possible

underestimation of the employment of women, the evidence seems to point

to unsatisfactory labour market outcomes in the period when India transited

to its much-celebrated high-growth trajectory.

* This article was originally published in The Business Line on July 26, 2011.

©

MACROSCAN 2011