Themes > Features

10.07.2012

Banking on Debt*

Besides

inflation, which has been an issue of concern for sometime now, the

main problem in macroeconomic management confronting the government

is the depreciation of the rupee. The currency has lost a fifth or

more of its value vis-à-vis the dollar over the last year,

and the bets are that it would move further downwards.

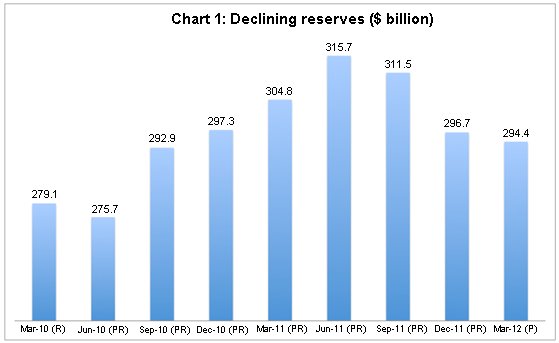

Needless to say, underlying that tendency must be changes in the balance

of payments that increase the demand for foreign exchange relative

to supply in India's liberalised foreign exchange markets. Signalling

that change is a decline in India's still comfortable foreign exchange

reserves, with Reserve Assets recorded in the country's international

investment position having declined from $315.7 billion at the end

of June last year to $294.4 billion at the end of March this year

(Chart 1).

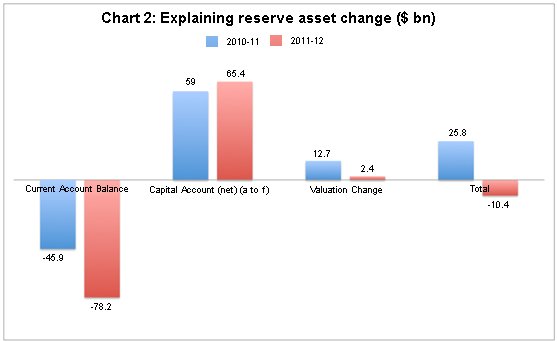

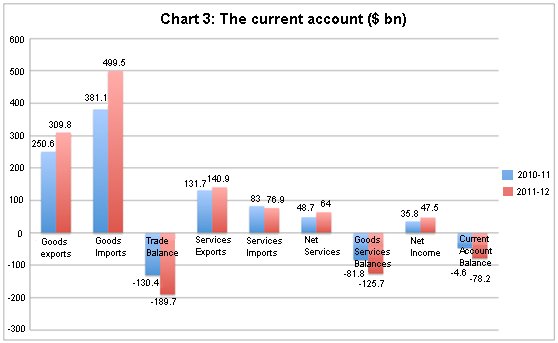

What is noteworthy is that one factor seems largely responsible for the widening of the current account deficit. As Chart 3 indicates, the only element contributing to the increase in the deficit is an increase in the import bill from $381 billion to almost $500 million. Exports in 2011-12 actually increased, and so did net income from services and net transfers. Thus, a rise in the import bill seems to be solely responsible for the deterioration in the current account. The RBI notes in its press release of June 29 on developments in India's balance of payment: ''In 2011-12, the CAD rose to US$ 78.2 billion (4.2 per cent of GDP) from US$ 46.0 billion (2.7 per cent of GDP) in 2010-11, largely reflecting higher trade deficit on account of subdued external demand and relatively inelastic imports of POL and gold & silver.'' While ''subdued external demand'' may be true of the fourth quarter of 2011-12, it is hardly true of the year as a whole. So what seems to explain the essential problem on the external front is the high oil import bill resulting from the prevailing high prices of oil in global markets and the high foeign exchange outlays on gold, which has become the target of speculative investment for rich Indians.

It should be clear from the evidence above that when attempting to address balance of payments difficulties and shore up the rupee, the government should focus on the import bill, since stimulating exports in the midst of a global recession would be difficult. Interestingly, however, the government's focus seems to be on attracting more capital flows. In its policy response, the government recently announced a set of measures aimed at increasing the space for and improving conditions for foreign financial investors in the debt market in India. The ceiling on FII investment in government securities has been increased from $15 billion to $20 billion and the residual maturity required for investments in excess of $10 billion has been reduced from 5 to 3 years. Quicker exit has been allowed even for FII investors in long-term infrastructure bonds (with a reduction in the lock-in and residual maturity requirement from 15 months to one year) and the Infrastructure Development Fund (with lock-in reduced from three years to one year and residual maturity fixed at 15 months). Finally, the government has now allowed new entities such as sovereign wealth funds, multilateral agencies, insurance companies, pension funds, endowments and foreign central banks to invest in government debt.

Thus,

it is not only the focus on capital inflows that distinguishes

the government's response, but the fact that when doing so it

seems to be favouring the debt market in particular. One reason

is of course that rules and regulations with regard to FII investments

in equity have been liberalised substantially in the past. The

other possibility is that the slack in debt inflows is perceived

to be greater, making debt flows more responsive to government

policy shift.

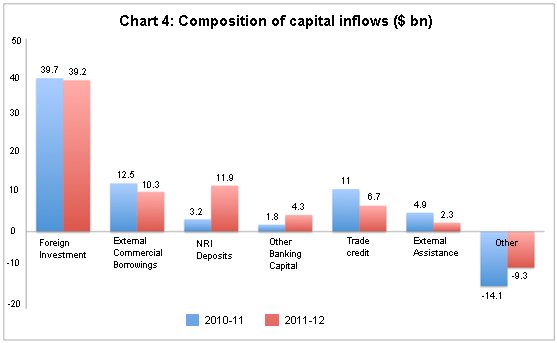

The evidence seems to support that perception. If we consider

2011-12 as a whole and examine the composition of capital inflows

(Chart 4), we find that though there was a change in the composition

of investment flows away from portfolio flows to direct investment

flows, the aggregate private investment flow into equity remained

more or less the same at $39-40 billion in both 2010-11 and 2011-12.

Not much should be made of the shift from portfolio to direct

investment, since the difference between the two merely consists

of the fact that direct investors are identified as those who

have cumulatively brought in capital equal to 10 per cent or more

of the equity in the target firm. Further, with the stock market

weak and volatile, investors may have preferred to stay out of

the FII route.

What is remarkable about the capital account is that inflows into

NRI deposits had risen from $3.2 billion in 2010-11 to as much

as $11.9 billion in 2011-12. This $8.7 billion increase in these

inflows exceeds the $6.4 billion increase in aggregate capital

flows, suggesting that they contributed to neutralising part of

the outflow under other heads. The increase in NRI deposits is

all the more noteworthy because that increase has largely been

in the non-resident external (NRE) rupee accounts, where remittances

from abroad are converted into and maintained in rupees in the

account. This implies that the foreign exchange risk is borne

by the depositor and not the bank. On the other hand, in the case

of foreign currency non-resident (FCNR) accounts, the deposit

is held in dollars and the bank carries the exchange rate risk.

Given the weakness and volatility of the rupee, one would have

expected that fear of the depreciation risk would have kept investors

away from NRE accounts. The reason why they have rushed into such

accounts is the decision of the RBI to deregulate interest rates

on non-resident accounts of maturity of one year and above in

the second half of the last financial year. Following the deregulation,

many banks have chosen to increase the interest rates on NRE and

NRO (ordinary non-resident) deposits, with some going in for extremely

large hikes. The State Bank of India, for example, raised the

interest rates on NRI fixed deposits of less than Rs. 1 crore

with a maturity of one to two years to 9.25 per cent from 3.82

per cent.

The net result is that despite the nil or extremely low interest

rates on premature withdrawal, non-residents have rushed into

these accounts. They are clearly speculating that the depreciation

cannot be as much as to wipe out the high differential between

these rates and international interest rates. The banks on the

other hand are betting that after taking depreciation into account

they would be paying a lower interest rate on these accounts than

on comparable domestic accounts. Matters went so far that the

RBI had to issue a circular cautioning banks against offering

such high interest rates. Reminding banks that the interest rates

offered on NRE and NRO deposits cannot be higher than those offered

on comparable domestic rupee deposits, the RBI also recommended

that ''banks should closely monitor their external liability arising

out of such deregulation and ensure asset-liability compatibility

from systemic risk point of view.''

In sum, there are two aspects to recent developments on the external

account. First there has been a significant increase in the reliance

on debt to finance a persisting current account deficit. As the

RBI recognised in a June 29 release, ''India's external debt,

as at end-March 2012, was placed at US $ 345.8 billion (20.0 per

cent of GDP) recording an increase of US $ 39.9 billion or 13.0

per cent over the end-March 2011 level on account of significant

increase in commercial borrowings, short-term trade credits, and

rupee denominated Non-resident Indian deposits.'' The second is

that this increase in debt has associated with it a significant

speculative component, which would increase the volatility of

those flows. This is to add another element of vulnerability to

the problems created by a high import bill, especially on account

of gold imports. The government may do well addressing the latter

vulnerability rather than encouraging further inflows of speculative

debt capital. However, its recent manoeuvres opening up the debt

market to foreign investors suggest that it is acting to the contrary.

Since government securities are tradable, foreign investors could

invest in them to speculate on expected movements in the rupee's

value. This could increase external vulnerability and may explain

why the rupee remains weak despite the comfortable absolute (even

if declining) levels of India's foreign reserves.

*

This article was originally published in Business Line dated 9

July, 2012.

©

MACROSCAN 2012