Themes > Features

25.07.2012

Another Looming Food Crisis*

Once

again food prices have reached exorbitant levels in world trade, surpassing

previous peaks and creating fears of another major global food crisis

of massive proportions. What is particularly shocking this time around

is how little has been learned from the last crisis just a few years

ago, and how criminally slow the international community and national

governments have been to put in place measures that would prevent

a recurrence of these crazy fluctuations in prices.

It is not just that public memory is short - the more worrying feature

is the denial on the part of policy makers about at least some of

the important factors that have caused these dramatic price fluctuations;

and the associated and continued refusal to take measures that will

address the problem. As the last round of food crisis builds up once

again and threatens the lives and material conditions of millions

of people across the world, it is imperative to take a close and hard

look at the evidence on global food prices and their determinants.

One major problem that prevents clarity of understanding on this matter

is the persistent belief that prices in global food markets are still

fundamentally determined by changes in real demand and supply. There

is no doubt that medium to long term trends are drive by this, and

that the expectations that drive speculative behaviour in food markets

are also deeply influenced by perceptions about changes in real demand

and supply. But the pattern of price behaviour in global food markets

in the past few years, and particularly the volatility in prices that

can be observed, bears much less relation to actual supply and demand

shocks, and much more to activity spurred by expectations about prices.

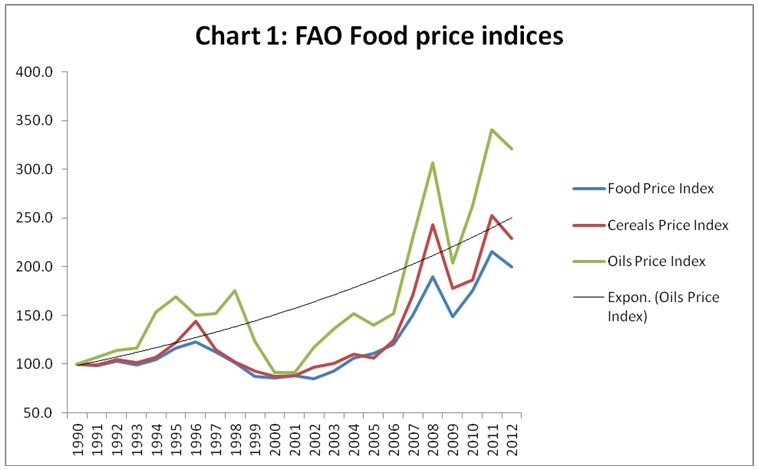

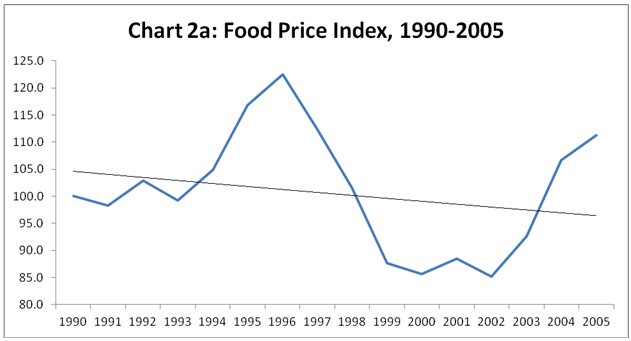

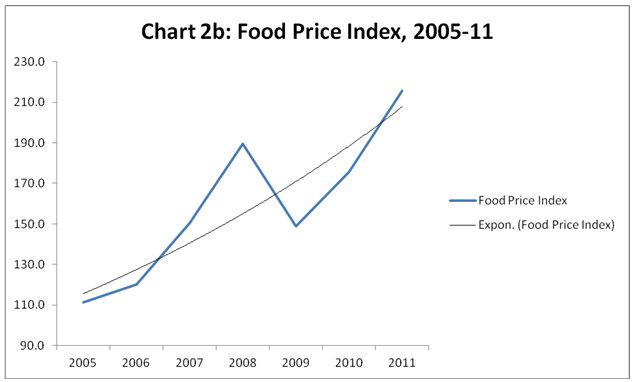

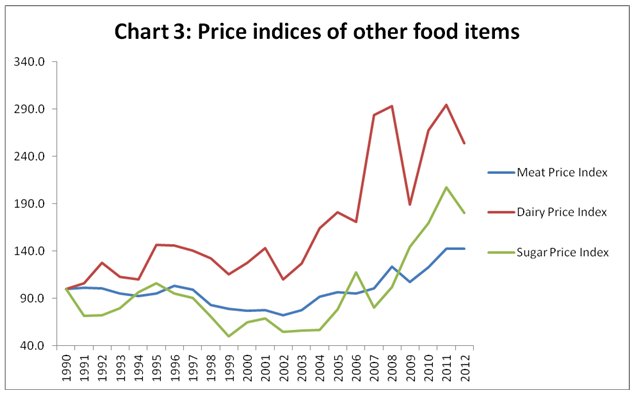

However, this conventional interpretation of the food price increase becomes less convincing when the period is broken down into sub periods. Charts 2a and 2b show that the period from 1990 to 2005 was quite different from the subsequent period in terms of food price changes. In the first period shown in Chart 2a there was some volatility to be sure, but the overall price trend over the period was if anything slightly downward. This is despite the same features described earlier - supply side issues like agrarian crisis in the developing world and insufficient agricultural investment as well as supposed demand side forces like more food demand stemming from rising incomes in low or middle incomes countries - being just as marked in that period, especially the later part of it.

In fact, the real change in prices comes after 2005, as prices zoom upwards on a volatile path around a rapidly rising trend. Obviously something much more was at work in this period than the medium term ''real'' tendencies that were described above. A further issue of significance that has affected grain prices is the impact of biofuel subsidies in the US and EU, which have diverted both acreage and maize production towards ethanol. Since these subsidies became large only from 2003 onwards, it is to be expected that the impact on grain prices would be felt after this.

But in the more recent period things have got even more complicated. Certainly it remains the case that financial activity in commodity futures markets remains strong and this plays a role in the price movements. And therefore there is obviously a strong case to be made for bringing all commodity trading onto regulated exchanges, restricting the role of purely financial players and enforcing strict position limits and other such measures.

The measures that have been implemented thus far are unfortunately halting and inadequate even in the US (which currently has the strongest such regulations with respect to commodity markets among advanced countries because of the Dodd-Frank Law). This has meant that in the context of very low interest rates and few other avenues of profitable financial investment, the incentives for private players continue to be loaded in favour of such speculation that can dramatically affect global prices of these essential items.

Even so, it is increasingly simplistic to suggest that this is all that is going on and that financial regulation of the kind noted above would be enough to curtail speculative activity in such markets. This is because large commodity traders themselves now engage more and more in what is essentially speculative activity, betting on changes in prices in order to benefit from these movements even beyond their requirements of the commodities for ''real'' purposes. The line between purchases of futures contracts for hedging or speculative purposes is now almost impossible to draw, especially as large agribusiness and commodity trading corporations have discovered that there is a lot of money to be made from purely financial dealings.

This obviously makes the problem of fixing the detail in financial regulation even more complex, but it also raises the issue of ensuring that the expectations that are driving such markets are controlled more effectively. Obviously, addressing issues of global supply - particularly through ensuring the greater viability of small scale production in the developing world - is of critical importance in this.

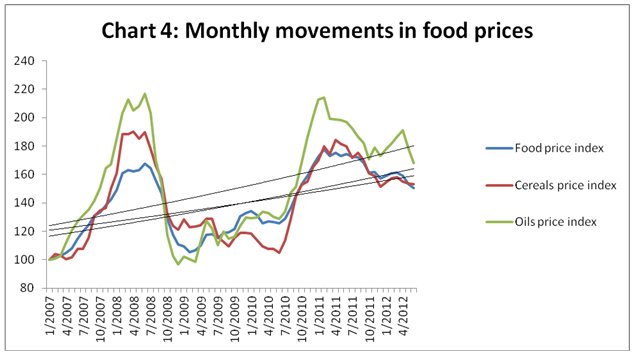

However,

the sheer volatility of recent price changes around this increasing

trend (as evident from Chart 4) suggests that even addressing

supply issues may not be enough. A related but slightly different

issue relates to the role of information and the nature of its

spread in what are essentially very opaque global markets. This

can be illustrated with reference to food grain markets, and particularly

the global wheat market. Wheat is widely seen as the most significant

traded grain and the role of futures contracts in this market

(particularly through the Chicago Board of Trade) is well-developed.

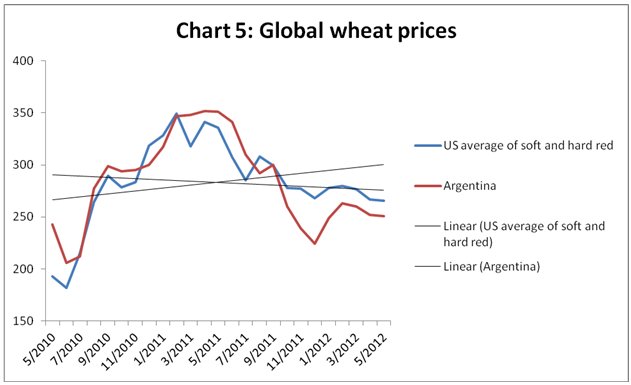

In the past two years, wheat prices have shown the highest volatility

in terms of monthly price changes. Chart 5 shows how prices of

US wheat nearly doubled in just six months, between June and December

2010, then fell again until early 2011 and then rose once more.

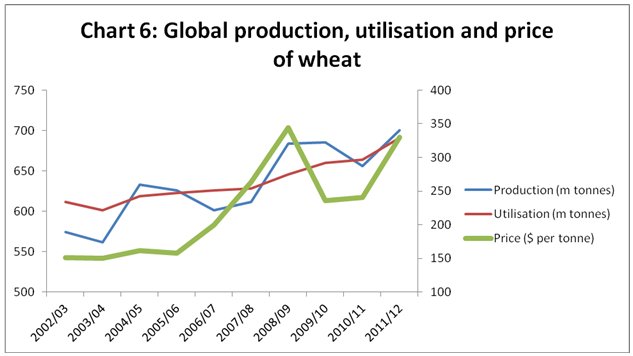

In

terms of ''real'' forces of demand and supply, however, the global

wheat market has been remarkably stable in the past decade. Chart

6 tracks the behaviour of aggregate global production and ''utilisation'',

which can be taken as a proxy for demand, according to FAO data.

In the entire period shown in this chart, both production and

utilisation have increased at average rates of around 2 per cent,

and indeed the rate of increase of production has been slightly

faster than that of utilisation overall.

Clearly, the price changes have borne little relationship to these

two forces. In fact, global wheat prices appear to have risen

in years when supply (production) was higher, often significantly

higher, than demand.

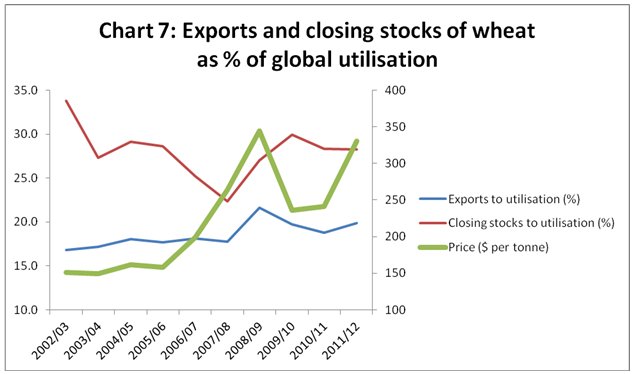

Chart

7 suggests that the price changes in the wheat market have also

had little to do with closing stocks of the same or previous period,

while exports have sometimes (but not always) responded to higher

prices. Of course, it needs to be noted that data on stock holding

is notoriously unreliable. FAO relies on data from governments

on their stock levels, but some governments do not reveal these

data (such as China). Possibly more significantly, there are no

data on private corporate stock holding, and given the size and

spread of multinational companies dealing in grain, this can also

be substantial.

So if it is not actual changes in demand and supply that explain

the price volatility, what is going on? One possibility worth

considering is the considerable role played by rumour, and therefore

by the media, in altering expectations. For example, in the period

from June 2010 when global prices rose sharply, the media were

full of reports about the failure of the harvest in Ukraine, a

major wheat exporter, and then replete with doomsday predictions

following on the export ban in Russia. These certainly drove up

price expectations and pushed up prices in the futures market

very quickly.

Subsequently, FAO data reveal that global production of wheat

had actually increased in this period, largely because of expanded

wheat output in Asia. But the period of sharply rising prices,

while it involved many losers including the poor throughout the

developing world, also had some winners. The large commodity trader

Glencore went for a public stock offering in early 2011, and when

doing so it revealed that it had doubled its profits the previous

years, largely because of gains made in the wheat trade.

Something similar is happening at present - the media are awash

with scaremongering stories about the drought in the US and other

factors affecting global grain supply. Already wheat prices in

the first half of July 2012 have increased by more than 22 per

cent, even though FAP estimates still suggest that globally this

will be a bumper year with a record wheat output. Once again poor

people will suffer because of higher food prices, without even

realising that private profiteering at different levels is generating

that disastrous tendency in global prices.

*

This article was originally published in the Business Line print

edition dated 24th July, 2012.

©

MACROSCAN 2012