Themes > Features

15.06..2010

The Good News about Health in West Bengal

Media

discussion about West Bengal has been largely negative in the past couple

of years, for a variety of reasons. Whatever be the merits or demerits

of those arguments, one problem with the conditions in the state that

has been identified by a number of observers in the recent past has

been the relatively poor performance in terms of human development,

especially health and education, relative to other clear successes in

land distribution, decentralization and power to panchayats, and so

on. Indeed, the fact that health indicators in West Bengal generally

lagged behind or at best kept pace with the national average was noted

in the West Bengal Human Development Report 2004.

The good news is that this picture seems to have been changing, especially

in the past decade. Recent data from the office of the Registrar General

of India, using the Sample Registration System (SRS), show that West

Bengal is now one of the best-performing states in the country in terms

of the most basic health indicators. The SRS is a large-scale demographic

survey of the Government of India, which is generally held to be providing

the most reliable annual estimates of fertility and mortality indicators.

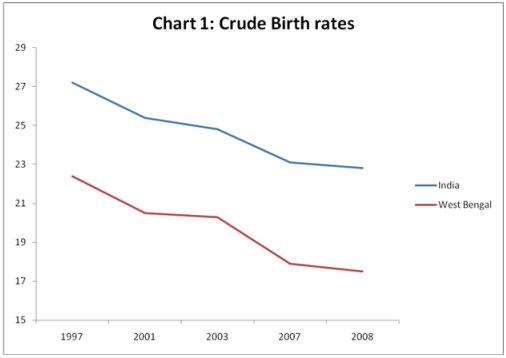

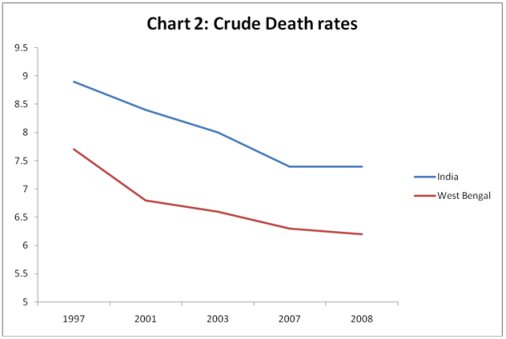

The charts here - which are all based on SRS data - show that the demographic

transition in West Bengal has proceeded more rapidly than for India

as a whole, and in a positive direction. In terms of both crude birth

rates (Chart 1) and crude death rates (Chart 2), the improvement has

been significantly greater than for India as a whole, even though the

state already had lower rates than the Indian average. The crude birth

rate (live birth per 1,000 people in a year) in West Bengal declined

from 22.4 to 17.5 between 1997 and 2008 (or by 28 per cent), compared

to a decline of 19.3 per cent for India as a whole. The death rate in

West Bengal fell by 24.2 per cent over the same period, as compared

to 20 per cent for India as a whole.

As a result, among the major states, West Bengal in 2008 had the fourth

lowest birth rate (after Kerala, Tamil Nadu and Punjab) and the lowest

death rate among the major states, even lower than that of Kerala. What

is also noteworthy is that the state’s rural-urban gap appears to have

been closing with respect to the death rate. In 2008, the rural death

rate in West Bengal was 6.1 compared to the urban rate of 6.6 (a gap

of 7.5 per cent) whereas for India as a whole it was 8.0 in rural areas

compared to 5.9 in urban areas (a gap of 26.2 per cent). Even Tamil

Nadu, the state that has otherwise performed very well in health indicators,

shows a rural-urban gap in the death rate of 23 per cent.

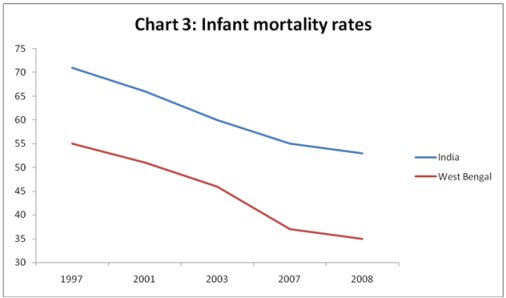

One major - and positive - reason for the decline in death rates is

the decline in infant mortality rates (IMR) in the state. The infant

mortality rate - expressed as the ratio of the number of death of infant

of one year old or less per 1,000 live births - is often regarded as

the single most important indicator of overall health conditions in

a particular area. This being the case, it is heartening to note that

the improvement in this indicator in West Bengal actually accelerated

in the most recent period, as compared to the Indian average where it

decelerated slightly (Chart 3).

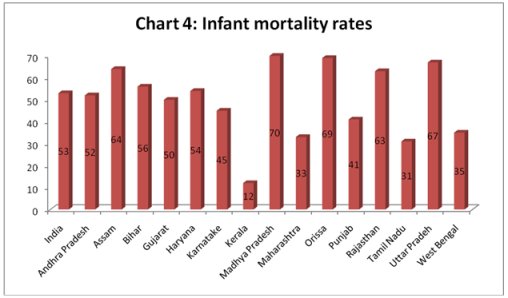

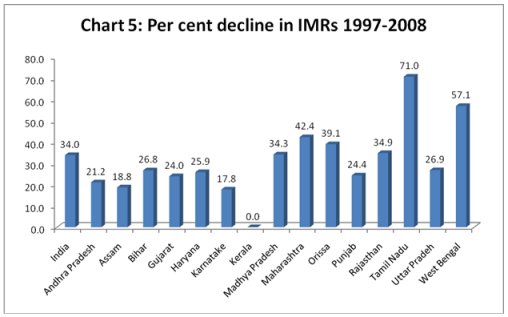

As Chart 4 shows, the decline in IMRs in West Bengal has made it one

of the best performing among major states with respect to this indicator,

placing it in fourth position after Kerala, Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu.

The rural-urban gap in the IMR has also improved, from 26 per cent in

1997 to 21 per cent in 2008, compared to the all-India gaps of 42 per

cent in 1997 and 38 per cent in 2008. Chart 5 shows how the state has

experienced the second largest decline in IMR among the major states

over the period, after Tamil Nadu.

What is worth noting

is that West Bengal throughout this period has had a very low gender

gap in IMR, thereby making it very different from several other states

of the country. This is also confirmed by other survey data – for example

the various rounds of the National Family Health Surveys have found

the gender gap in IMR to be either the lowest or among the lowest in

the country.

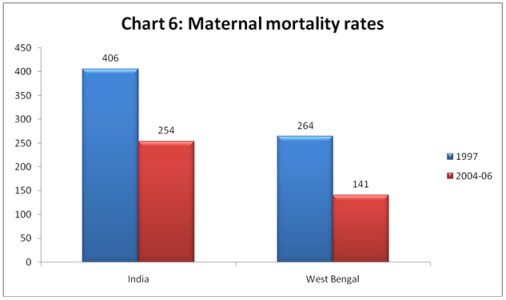

The

other very important indictor of both health conditions and the status

of women is the maternal mortality ratio (MMR), which is the rate of

maternal deaths per 100,000 live births among women aged 15-49 years.

Once again, MMRs are lower in West Bengal than the national average,

and have been declining faster as well. The lifetime risk of maternal

death (defined as the probability that at least one woman of reproductive

age of 15-49 years will die during or just after childbirth assuming

that the chance of death is uniformly distributed across the reproductive

span) was only 0.3 per cent in West Bengal in 2004-06, compared to 0.7

per cent for all India and 0.2 per cent in the best-performing state,

Kerala.

Obviously, while these improvements are praiseworthy, there is still

a long way to go in terms of improving even these basic health indicators.

The differences between West Bengal and the best-performing state Kerala

still remain substantial, suggesting that appropriate policy interventions

can continue to make significant improvements in these indicators.

But the question remains: what accounts for this recent improvement

in health indicators, especially in relation to the rest of the country

other than Tamil Nadu? A number of possible explanations can be considered.

First, there has been a general improvement in institutional conditions,

especially in the West Bengal countryside, in terms of the number of

hospitals and health facilities and the increase in access of women

to ante-natal and post-natal services. This has been enabled not only

by increased public expenditure in certain areas, but also by a programme

of more decentralised public health delivery, with greater autonomy

given to local and village health committees in terms of spending and

care systems. Thus, the NFHS surveys have found that there was a gradual

increase in the percentage of mothers who made at least three antenatal

visits during their last birth in West Bengal, from 50.3 per cent in

1992-93 to 62.4 per cent in 2005-06. This compares favourably with the

national averages, which were significantly lower.

Second, since health is intimately related to both sanitation and nutrition,

some improvement in both of these variables is also likely to have played

a positive role. The extension of better sanitation facilities to rural

areas has accelerated, even though overall these facilities still remain

inadequate. It is likely that the improvement in both IMR and MMR has

been most marked in those districts where the sanitation programme has

been more successful. Similarly, targeted schemes for maternal nutrition,

implemented through the ICDS and other programmes, are also likely to

have had positive impact.

Clearly, therefore, there are signs of substantial progress in basic

health indicators in West Bengal in recent years. The question of why

these have gone largely unnoticed in both the national- and the state-level

media is, of course, an entirely different issue.

©

MACROSCAN 2010