| |

|

|

|

|

Food

Price Transmission in South Asia* |

| |

| Jun

14th 2011, C.P. Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh |

|

The current food price surge is raising the spectre

of a renewed and possible even more ferocious global

food crisis, with significant increases in food insecurity

in the poorest countries. But this time, there are some

dissenting voices, including those who argue that possibly

the earlier recent bout of food price increases (which

occurred over 2006-08) did not have as bad an impact

on hunger and undernutrition as was earlier believed.

Indeed, it is being argued by some that in fact the

extent of hunger in the developing world may actually

have come down significantly even during that period

of dramatic food price increase.

Most estimates of increasing hunger are based on simulation

exercises that take note of global food price increases

and assume that these will lead to domestic increases

in food price which will in turn affect food consumption,

especially of poorer families. Against this, it is argued

that such exercises do not take account of increasing

money incomes and people's choices about what to consume.

A recent paper by Derek Headey (''Was the global food

crisis really a crisis? Simulations versus self-reporting'',

IFPRI Working Paper No 1087, 2011, available at http://www.ifpri.org/publication/was-global-food-crisis-really-crisis)

argues that global self-reported food insecurity fell

from 2005 to 2008, with the number ranging anywhere

between 60 million to 250 million. This is based on

calculations using a Gallup World Poll of self-reported

food insecurity. According to Headey, ''These results

are clearly driven by rapid economic growth and very

limited food price inflation in the world's most populous

countries, particularly China and India.'' This idea

has also been taken up by others such as Dani Rodrik.

Of course, there are significant problems with using

self-reporting of hunger at the best of times. The Gallup

Poll asks the question: ''Have you or your family had

any trouble affording sufficient food in the last 12

months?'' The percentage of respondents who answer yes

to this question is taken as a measure of national food

insecurity.

It

is worth looking carefully at the Gallup Poll methodology

before we decide to jump to hard conclusions, though.

The Gallup report on its food security survey notes

that it is based on telephone and face-to-face interviews

conducted throughout 2005, 2006, 2007, and 2008, with

randomly selected sample sizes (typically around 1,000

residents) in 134 countries - so a total of less than

140,000 people across the world, and only 1000 respondents

even in huge countries like India. The distribution

of the samples across urban and rural locations or by

income category is not clear at all, nor is the proportion

that was contacted by telephone. This is not exactly

a solid basis on which to draw major conclusions on

the extent of global hunger.

The Gallup Poll people themselves do not seem to think

they can make intertemporal comparisons based on these

data: their own conclusion is that ''even before the

crisis, affording food was a challenge for many''. Basing

a major conclusion on this rather weak ''self-perception''

data, as Headey does, is really not justifiable.

Of course, Headey is quite right to point out that there

may be differences in the impact of global food prices

upon consumers in developing countries, depending on

the extent to which such prices are transmitted to domestic

retail food prices, as well as the opportunities of

earning incomes that allow more expensive food to be

purchased. It is certainly also the case that the negative

effect of food prices can be mitigated by other factors

and policies such as employment schemes, subsidised

food distribution and so on.

Even so, it is indisputable that the main mechanism

through which higher global food prices affect people

remains domestic food prices. Here, the bad news is

that the international transmission of increases in

food prices has generally been rapid (and is getting

faster and more complete) while the downward movements

have not been transmitted so much.

What may be even more significant is that even in India,

which is taken (along with China) by Headey and others

to be a major part of the explanation of the supposedly

surprising result about reduced food insecurity, food

prices have risen sharply over the past few years. The

more disturbing feature is that domestic prices have

increased along with international prices, but there

has been little transmission of downward price trends,

indicating some kind of ratchet effect in domestic prices.

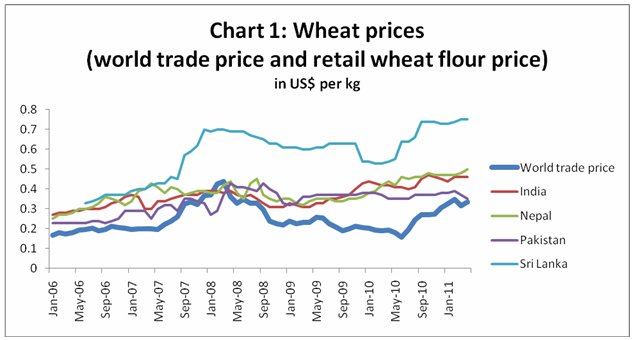

These tendencies are evident from a consideration of

South Asian countries. The accompanying charts are all

based on data from the FAO GIEWS (Global Information

and Early Warning System) online database. Chart 1 provides

information on wheat prices in global trade as well

as retail prices of wheat flour in domestic markets

of four South Asian countries, all in US $ per kg.

Chart

1 >> Click

to Enlarge

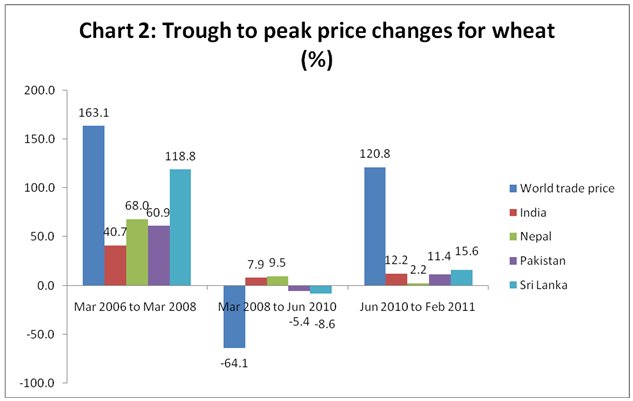

Chart 2 elaborates on the evidence in Chart 1 by noting

the extent of trough to peak and peak to trough changes

in wheat/wheat flour prices, both internationally

and in these domestic markets. The dramatic price

increase in global wheat prices, more than doubling,

was met by sharp price increases also in South Asian

countries. The increase in prices was indeed lowest

in India, which has a greater degree of self-sufficiency,

but even in India wheat flour prices rose by 40 per

cent over the first period of price rise between March

2006 and June 2008. This is a very significant increase

in a country where around 95 per cent of workers'

incomes are not indexed to inflation.

Further, when global wheat prices fell, domestic retail

wheat flour prices continued to increase in India

and Nepal, and fell only marginally in Pakistan and

Sri Lanka. So the force of downward international

price transmission is much weaker if not non-existent.

The implication comes out even more sharply from Chart

3, which show the change in price levels for wheat

compared to March 2006. By June 2010, wheat prices

in global trade were down to lower than the level

of March 2006, despite having increased so dramatically

in between. But in all the South Asian countries considered

here, prices in June 2010 were still significantly

higher than they had been in March 2006. And of course,

they continued to rise in the subsequent period, when

global prices also rose once again.

Chart

2 >> Click

to Enlarge

Chart

3 >> Click

to Enlarge

However, the recent very sharp rise in global wheat

prices, since June 2010, has clearly not yet filtered

into changes in retail prices in South Asia. To some

extent this may be because good rabi harvests in the

region have ensured that domestic supplies are adequate.

However, the impact of expectations - and the associated

role of financial players - is now growing even in

these markets, especially in India where wheat futures

markets have been allowed to function once again.

Therefore it is likely that the near future will once

again see some further international price transmission

even in these markets.

Similar patterns are evident in rice, even though

this is a grain which has a relatively small and shallow

global trade market (for example, India's annual rice

output is more than six times total world trade in

volume terms).

Chart

4 >> Click

to Enlarge

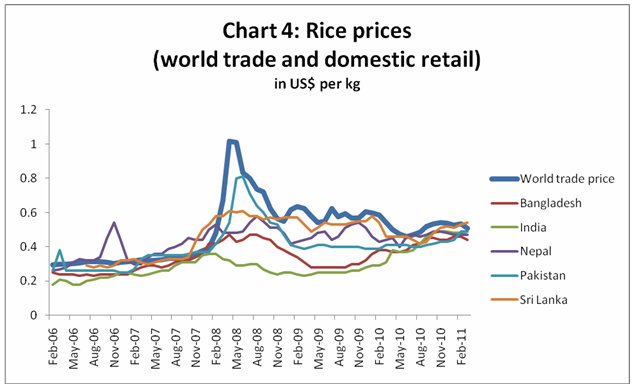

Chart 4 shows the monthly behaviour of rice export

prices as well as domestic retail prices of rice in

five South Asian countries. The transmission of rising

global rice prices appears to be especially acute

in Pakistan and Sri Lanka, both of which import rice

to the extent of around one-third of domestic consumption.

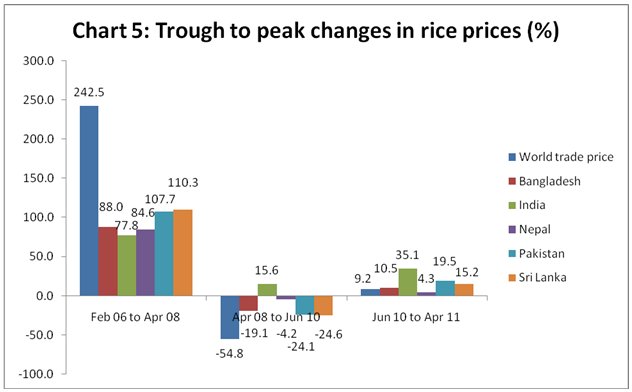

But in the case of these countries, as Chart 5 shows,

the downward transmission of falling prices also occurred

to some extent - although once again to a lesser extent.

It is worth noting that in India retail prices of

rice kept rising through all phases, and indeed in

the most recent phase have risen faster than global

prices.

Chart

5 >> Click

to Enlarge

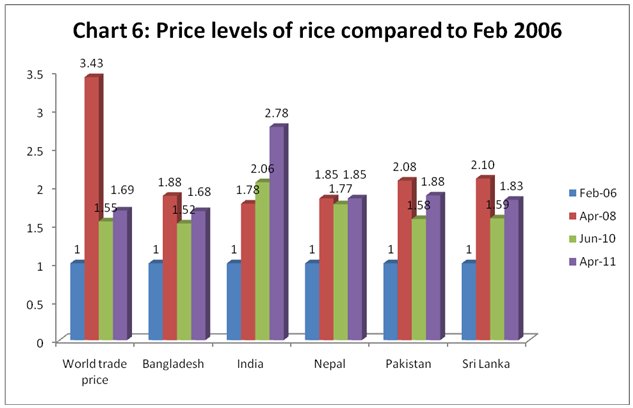

As

a result, as evident from Chart 6, Indian rice prices

are now nearly three times higher than they were in

February 2006, even though global rice prices are now

only 69 per cent higher. In fact, other than Bangladesh,

the current level of rice prices is higher in all the

South Asian countries than in February 2006, in comparison

to world prices.

So domestic factors celarly do play a role in the international

transmission of food grain prices, especially at the

retail level. However, this analysis also shows that

global prices do put upward pressure on domestic prices

when they are rising, even though downward movements

are less rapidly or effectively transmitted and often

do not have any such impact.

This clearly calls for more detailed investigation into

the factors operating at different levels in various

countries, and particularly the policy mix that will

enable countries with large hungry populations to withstand

the current global volatility in food prices.

Chart

6 >> Click

to Enlarge

*

This article was originally published in The Business

Line on 14 June, 2011

|

| |

|

Print

this Page |

|

|

|

|