| |

|

|

|

|

India's

Schizophrenic Banks* |

| |

| Jun

29th 2011, C.P. Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh |

|

In a move that is commendable, the Reserve Bank of India

(RBI) has decided to continue with its recent practice

of issuing periodic Financial Stability Reports (FSRs),

or assessments of the strength and resilience of the

financial system. Last year, reports were issued in

March and December. Starting this year, biannual reports

are to be issued in June and December. The June 2011

report reveals much that is known about the Indian financial

system: that it is still dominated by banking, that

banks rely largely on deposits for their funds, that

the allocation of funds pointed to stability, and that

the banks were on average well capitalised. Deposits

accounted for 79 per cent of total liabilities, and

advances and investments constituted 87 per cent of

total assets, with investments alone amounting to 30

per cent. Since government securities are an important

component of investments, they substantially shored

up the balance sheets of banks.

Despite these features of the banking system, the RBI's

report is characterised by a muted sense of concern.

The reasons for that concern are specified, though often

the exact numbers involved are difficult to glean because

they appear in unlabelled graphs.

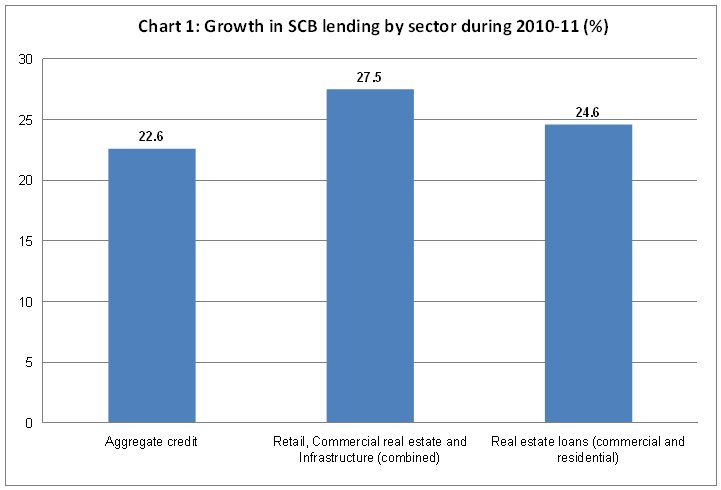

The first of the RBI's causes for concern is the evidence

that in recent times banks seem willing to accommodate

borrowers, even if that required them to rely on more

costly funds mobilised by issuing certificates of deposit

or through borrowing. The share of CDs and borrowing

in the total liabilities of banks rose from around 7

per cent in the middle of 2009 to 10 per cent at the

end of March 2011. This reliance on higher cost funds

was the result of an increased proclivity to lend, resulting

in periodic credit booms. Credit growth rose sharply

to 22.6 per cent in 2010-11, which called for caution

since past experience shows that the process of impairment

of assets begins during a credit boom. Further, besides

the fact that these funds were costlier than conventional

deposits, they were often characterised by short maturities,

leading to increasing maturity mismatches between the

sources and uses of funds. To quote the FSR: ''While

more deposits than advances were getting re-priced in

the near term (less than a year) bucket, more advances

than deposits were maturing in 1-3 year and 3-5 years

buckets.'' This kind of a credit boom, experience from

elsewhere suggests, can result in an accumulation of

excessive risk and an increase in bank fragility. What

is reassuring is that while this was the tendency at

the margin, these kinds of funds were a small share

of the stock of resources with the banks, with low cost

current and savings deposits accounting for 35 per cent

of total deposits.

The causes for concern were not restricted to the pace

of expansion of credit and the pattern of fund raising

by banks. They also came from the sectoral composition

of credit expansion, with incremental credit concentrated

on a few sectors, especially sensitive ones like retail

lending (including housing), commercial real estate

and infrastructure. Here too there was a difference

between the stock of credit assets created by banks

and changes at the margin. While on average the credit

portfolio of banks was diversified across sectors and

geographies, in recent years the sectors named earlier

have gained in prominence. The combined credit to these

sectors increased by 27.5 per cent in 2010-11, as compared

with aggregate credit expansion of 22.6 per cent (Chart

1).

Chart

1 >> Click

to Enlarge

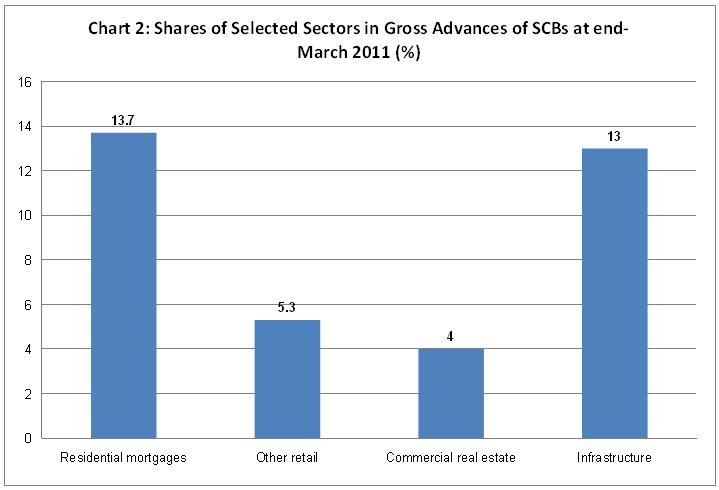

Their combined contribution to the increment in gross

outstanding credit between the end of March 2009 and

the end of March 2011 was 40 per cent. In the event,

at the end of March 2011, the retail, commercial real

estate and infrastructure sectors accounted for 19,

4 and 13 per cent of the gross advances of the scheduled

commercial banks. As Chart 2 shows, residential mortgages

and infrastructure were especially important targets

of SCB lending.

On the surface, it appears that lending to the real

estate sector should not give much cause for concern.

The share of non-performing assets (NPAs) in the real

estate sector relative to total NPAs was, at 15 per

cent, lower than the sector's share in total advances

of 17.7 per cent. But things seem to be changing.

The rate of growth of NPAs in the real estate sector

was, at 19.8 per cent, significantly higher than the

rate of growth of aggregate NPAs of 14.8 per cent.

Moreover, NPAs in the commercial real estate segment

grew at an astounding 70.3 per cent. With many banks,

including public sector banks having attracted borrowers

with schemes such as those involving low teaser interest

rates in the initial years, and interest rates on

the rise in the economy this does increase the risk

of loan impairment in the sector.

Chart

2 >> Click

to Enlarge

Besides residential mortgage, risks abound in the

remaining part of the retail lending segment as well,

though that accounts for a small share of total lending.

Those loans are significantly riskier and largely

unsecured. Yet, such lending has been on the rise,

given the higher interest rates that can be charged

for them.

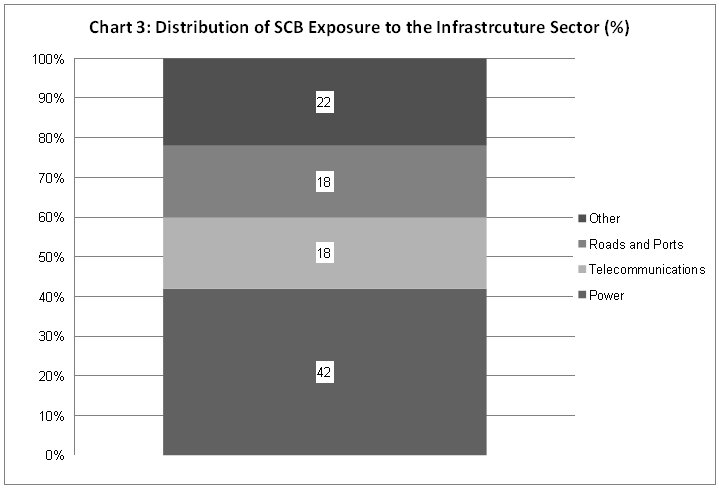

Finally, the surprising trend is with respect to bank

exposure to the infrastructural sector. Lending here

is largely to the Power, Roads and ports and Telecommunications

sectors. These are areas where, post liberalisation,

private entry has been sudden and substantial, resulting

in huge demand for credit. Banks, including private

banks have chosen to step in, resulting in the sector

accounting for a significant share of SCB advances.

Power alone accounted for 42 per cent of aggregate

infrastructure credit at the end of March 2011, with

the other two sectors garnering 18 per cent each (Chart

3). This sets up two kinds of risk. First, the excessive

exposure of banks to a few of these sectors, when

the aggregate level of exposure is by no means small,

is a source of enhanced risk. Second, given the long

gestation lags associated with these projects, which

can be worsened by delays in project implementation,

commercial bank lending to them is bound to be associated

with significant asset liability mismatches and the

associated risks.

There are three features of bank lending to infrastructure

that need to be noted. First, as of now the ratio

of NPAs to advances in this sector is low, amounting

to 0.5 per cent. But that is partly because significant

bank lending to this sector is recent. It is likely

that the contribution of this area to NPAs would increase

over time. Thus, in 2010-11, there was an increase

of 42.5 per cent in the impaired loans to the infrastructure

sector. Second, it is true that many projects have

a guarantee of returns to investment. But this is

true mainly in the power sector and that too for the

fast track power projects. Finally, exposure to the

infrastructure structure is concentrated among public

sector banks, which account for 84.8 per cent of banking

sector exposure to these industries. Hence, it may

be attributed to government policy rather than autonomous

bank behaviour. This, however, does not reduce the

risk of default and of resulting fragility and failure,

especially since lending is directed significantly

at private sector firms. Moreover, in recent times

the exposure of the new private banks and the foreign

banks to this sector has risen significantly, indicating

that the ''dynamism'' in this newly liberalised sector

is also an explanation for bank interest.

Chart

3 >> Click

to Enlarge

Thus, as of today bank behaviour in India appears

almost schizophrenic, with the evidence pointing to

both caution and an increased appetite for risk. In

the aggregate, banks appear cautious and restrained

with a funding base and asset portfolio that point

to resilience and capital adequacy ratios that are

more than adequate. But at the margin they display

behavioural characteristics that point to increased

risk-taking of a kind that could lead to fragility

and failure, resulting in the regulator's concern,

however incipient. Clearly, caution is a legacy, while

risky behaviour is the new norm. Concern is, therefore,

warranted.

What could explain this behaviour? One obvious explanation

is the quest for profit that encourages players, public

and private and big and small, to diversify in favour

of sectors like retail lending and real estate. But

that alone cannot explain the change in this direction.

The change has clearly been influenced by liberalisation

that allows banks, public and private, to behave in

this manner. So long as capital adequacy ratios are

within prescribed ranges, regulation does not prevent

or significantly constrain behaviour of this kind.

A third explanation is the inadequacy of opportunities

to lend at a profit to the commodity producing sectors

that are languishing. The consequence is increased

lending to units in the services sector and to infrastructure,

besides the retail segment. Finally, there is the

demonstration effect. With public sector banks still

dominating the banking space, it may be expected that

legacy behaviour would dominate the new tendencies.

But the example set by the new private sector banks

and the foreign banks in residential mortgage and

retail lending and in lending to commercial real estate,

not just encourages but in fact forces public sector

banks to do the same. In the event, in certain areas,

such as the provision of teaser loans, the public

sector banks are even willing to go even further.

The observed outcome is a result of all of these factors

and more.

*

This article was originally published in The Business

Line, 28th June 2011.

|

| |

|

Print

this Page |

|

|

|

|