The failure of the Indian state more than six decades

after Independence to provide universal access to

quality schooling, and to ensure equal access to higher

education among all socio-economic groups and across

gender and region, must surely rank among the more

dismal and significant failures of the development

project in the country. It is not only that the expansion

of literacy and education has been far too slow, halting

and even geographically limited. It is also that educational

provision itself remains highly differentiated in

both quantitative and qualitative terms.

There

are huge differences in access to both schooling and

higher education across location (rural/urban or state),

economic category and social group, as well as by

gender. And there are very significant variations

in quality of institution across different schools,

colleges and universities, which mean that the experience

of education is very different for different students.

These differences in quality cannot be simplified

into government or public versus private as is quite

commonly done in journalistic discourse: there are

some very good government schools and some terrible

private schools; and in general public higher educational

institutions perform much better than private ones.

All the so-called ''institutions of excellence'' in

higher education are publicly created and publicly

funded institutions. Rather, the differences in quality

often unfortunately reinforce differences on the basis

of location and social divisions.

Thus, institutions in backward areas and in educationally

backward states tend to be both underfunded and of

poorer quality than institutions in metros or in more

educationally developed states. Rural schools are

often worse than urban schools (although once again,

this is not inevitable) and schools catering to elite

or middle class children tend to be better than schools

for urban poor serving slum children or rural schools

serving the children of agricultural labourers. Schools

with dominantly upper caste children also tend to

provide better services than schools mostly catering

to SC or ST or Muslim children. School with only girl

students are more likely to be deficient in basic

facilities, including toilets and fans in classrooms,

as well as teaching aids. And so on.

These differences in quality of schooling have significant

implications, because they do not simply affect the

quality of education per se, they also affect chances

of entry into higher education and the possibilities

of socio-economic advancement that come from such

entry.

Thus, access of deprived social groups is adversely

affected not only by sheer quantitative variations,

but also by differences in quality of schooling. Since

this acts as a filtering process for further education,

it is not surprising that evidence of exclusion grows

as one goes up the education ladder. Obviously intelligence

and merit must be normally distributed in society.

So these very strong indicators of differential access

to higher education across social groups do not reflect

actual differences in the innate quality of aspiring

students, but socio-economic discrimination that reduces

the chances of many meritorious students even as it

privileges the children of the elite who have access

to ''better'' schooling. This is why the process of

democratising even higher education cannot proceed

very far without ensuring much more equitable social

access to good quality schooling.

All this, in turn, is critically determined in the

first instance by public funding. It is difficult,

if not impossible, to impart quality education ''on

the cheap''. You cannot ensure quality without reasonably

good infrastructure, sufficient numbers of trained

and adequately compensated teachers, other amenities

and teaching aids, including access to new technologies

that are becoming an essential part of contemporary

life. Yet the attempts to universalise school education

have all too often been associated with just such

a tendency, relying on underpaid ''parallel'' teachers,

who in turn are forced to function with completely

inadequate infrastructure and lack of even basic facilities.

Ensuring a reasonable quality of education to all

children – and thereby also ensuring a greater democratisation

of the entire process - necessarily requires a significant

expansion of the resources to be provided to elementary

school education. It is not just the need to expand

the system to cover all children, as described in

the Right to Education Act, which determines this.

It is also because existing institutions have to be

upgraded so that they qualify as schools providing

good quality education.

This is even more important because of the need to

upgrade the ''Education Centres'' that are operating

in many states to proper schools that meet all the

norms in terms of trained teachers, minimum facilities,

etc. Also, in the urge to increase the coverage of

secondary education, many primary schools are being

upgraded to secondary school status, without provision

of sufficient teachers, rooms and other pedagogical

requirements, such as provision for specialised subject

teachers, science labs, counselling etc. This severely

comprises on the quality of such secondary school

education.

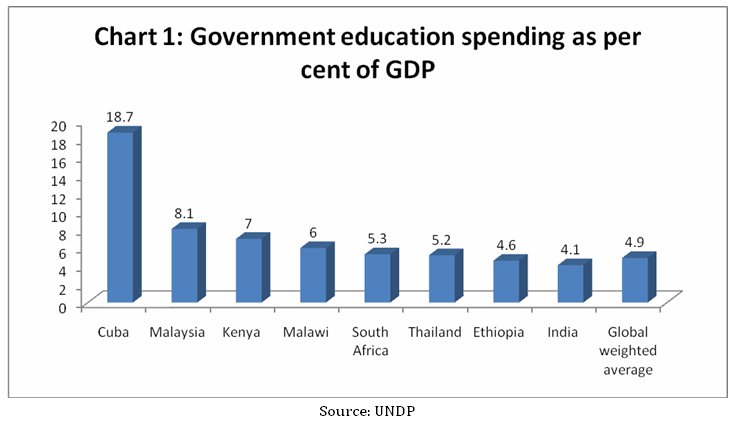

This is the context in which public expenditure on

schooling must be assessed. This is not something

that the current government is unaware of: indeed,

from UPA-1 onwards, the necessity for greater public

spending on education has been openly acknowledged

in official quarters. The National Common Minimum

Programme of UPA-1 pledged to raise public spending

in education to least 6 per cent of GDP with at least

half this amount being spent of primary and secondary

sectors. While there was some increase in central

government expenditure, this particular goal was nowhere

near being achieved in the first tenure of the UPA,

with public spending on education remaining at around

4 per cent of GDP, and certainly well below 5 per

cent. The second tenure of the UPA has even been marginally

worse, with no significant increase in allocations

for education.

As evident from Chart 1, this is an embarrassingly

low ration even by the standards of other developing

countries. It is less than a quarter of the equivalent

ratio in Cuba, but even well below the percentage

of public spending on education to GDP in countries

like Kenya, Malawi and Ethiopia. And despite the UPA's

promises and recent endeavours, the ratio in India

is still substantially below that of the weighted

average of all the countries in the world.

Chart

1 >> Click

to Enlarge

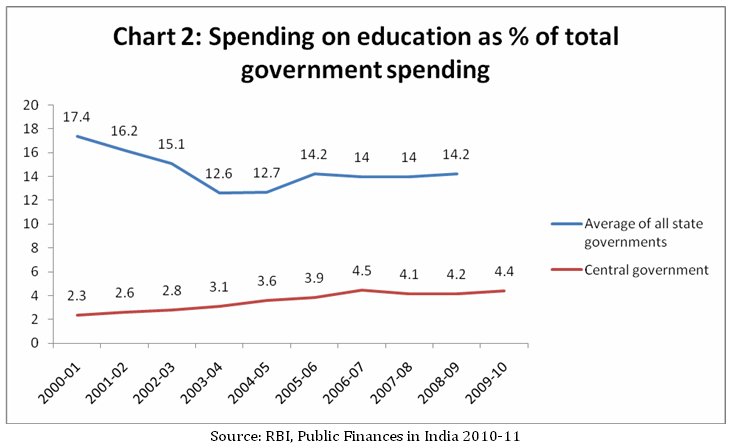

To make matters worse, instad of providing a big increase

in funding for school education, the central government

(UPA-2) has actually retracted by reducing its commitment

on Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan from 75 per cent to 50 per

cent. This is a big blow, not only for those states

where school education is still far from universal,

but also in other state where there is pressing need

for more funds to improve the quality of schooling.

Chart

2 shows that state governments taken together are

currently spending around 14 per cent of the total

expendtiure on education at all levels, a decrease

from the level of a decade ago but an increase compared

to the middle years of the previous decade. But the

central government's declared desire to increase education

spending is barely reflected at all in the budgetary

figures, and the amount spent on education remains

a shockingly low proportion of total public spending.

Chart

2 >> Click

to Enlarge

Of course it is true that resources alone are not

enough. There are many other changes and reforms required

in our school and higher education systems: greater

decentralisation, greater flexibility, changing patterns

of examination, different and more creative and relevant

teacher training, and so on. But significantly higher

levels of public funding are the necessary precondition

for any other reforms to be successful, and indeed

to even dare to hope for improved quality of education.

Surprisingly,

even this rather obvious conclusion has become a matter

of debate in India at present. It is generally agreed

that more resources are required for education, but

there are arguments that instead of relying on more

public funding, there should be greater freedom granted

to private provision of education. According to this

view, there is no reason for the state to get into

education provision, and instead it should focus on

creating an ''enabling environment'' for private provision,

even if necessary by recognising the possibility of

profit-making investment in education as in Singapore.

There are several levels of response to this argument.

First, the significant presence of positive externalities

in education (which means that the benefits of providing

education extend beyond the agent that is spending

the resources, to society as a whole) means that if

it is left only to private hands it will be significantly

underprovided, and poor children in backward areas,

for example, will simply not be reached.

In any case there are good reasons why commercialisation

of education is actually prohibited by law in India

(even though it is – as with so many other laws –

often more honoured in the breach). The possibility

of being exploited by unscrupulous private providers

who take advantage particularly of those who do not

have the access to information or training that would

allow them to discriminate, is very high. That is

why the explicit legal and official focus has been

to encourage charitable institutions like trusts and

educational societies to provide private education.

This has not prevented all sorts of other private

education institutions from coming up, and naturally

there is immense variation. There are excellent institutions

with very good track record, inclduing those which

are actively engaged in affirmative action to ensure

greater access of underprivileged children. At the

opposite end, there are crammed tutorial centres and

hole-in-the-wall teaching shops masquerading as ''English

medium'' schools to profit from the unmet hunger for

education that is so marked across India.

A recent survey (India Human Development Survey 2010)

of 41,554 households across India allows us to compare

the incidence of private schooling and the relative

costs of such schooling across states. The results

are shown in the accompanying table, from which several

interesting features emerge. The ratio of private

enrolment in schools for children aged 6-14 years

varies dramatically across states, from a low of 6

per cent in Assam to a high of 52 per cent in Punjab.

While both Punjab and haryana have high ratios of

privatisation of schooling, it is not as if this feature

is otherwise strongly correlated with per capita income

in the state. Nor is it that private education is

always greater where public education is less funded

(defined by the per capita annual total expenses in

Government schools), or even where the gap between

public and private funding is large.

What is clear from the table is that per captia expenditure

is a critical variable in affecting quality. Thus

Kerala, which is generally acknowledged to have a

good government schooling system, has one of the highest

per capita spending values. The highest was found

in Himachal Pradesh, which is one of the great recent

success stories of school education, and has achieved

universal and good quality school education despite

being a relatively less wealthy state and having to

deal with difficult terrain and logistical constraints.

The table reinforces the point that to ensure quality,

raising the level of public expenditure in education

is absolutely essential.

Table

1: Schooling costs for children aged 6-14 years |

|

Private

school enrolment (%) |

Annual

total expenses per student (Rs)

|

Government

|

Private

|

All

India |

28 |

688 |

2920 |

Andhra

Pradesh |

31 |

574 |

3260 |

Assam |

6 |

371 |

1636 |

Bihar |

18 |

704 |

2466 |

Chhattisgarh |

15 |

317 |

2039 |

Delhi |

28 |

1044 |

5390 |

Gujarat |

22 |

766 |

4221 |

Haryana |

47 |

1043 |

4372 |

Himachal

Pradesh |

19 |

1709 |

6273 |

Jammu

and Kashmir |

47 |

1045 |

3719 |

Jharkhand |

32 |

502 |

2932 |

Karnataka |

28 |

638 |

3848 |

Kerala |

31 |

1537 |

3259 |

Madhya

Pradesh |

27 |

333 |

1935 |

Maharashtra,

Goa |

20 |

599 |

2370 |

North-East |

34 |

1441 |

4237 |

Orissa |

8 |

612 |

2851 |

Punjab |

52 |

1444 |

5160 |

Rajasthan |

32 |

676 |

2612 |

Tamil

Nadu |

23 |

606 |

3811 |

Uttar

Pradesh |

43 |

427 |

1733 |

Uttarakhand |

27 |

972 |

3422 |

West

Bengal |

10 |

1136 |

5045 |

|

Source:

Human Development in India: Challenges for a

society in transition, OUP 2010, page 84. |

Table

1 >> Click

to Enlarge

All this is especially important now that the Right

to Education has become enshrined in law. If the central

government is really serious about this, it must put

its money where its mouth is.

*

This article was originally published in The Frontline,

Volume 28, Issue 14, July 2-15, 2011.