Themes > Features

04.03.2009

Whatever's happened to Global Banking?

After

having failed to salvage a crisis-afflicted banking system by guaranteeing

deposits, providing refinance against toxic assets and pumping in preference

capital, governments in the US, UK, Ireland and elsewhere are being

forced to nationalize their leading banks by buying into new equity

shares. What is more, even staunch free market advocates like former

Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan, who made the case for regulatory

forbearance and oversaw a regime of easy money that fueled the speculative

bubble (which he declared was just ''froth''), now see nationalization

as inevitable. In an interview to the Financial Times, Greenspan, identified

by the newspaper ''as the high priest of laisser-faire capitalism'',

said: "It may be necessary to temporarily nationalise some banks

in order to facilitate a swift and orderly restructuring. I understand

that once in a hundred years this is what you do."

This ideological leap has come at the end of a long transition during

which the understanding of the nature of the problem afflicting the

banks in these countries has been through many changes. Initially, when

the subprime crisis broke, this was seen as confined to subprime markets

and to institutions holding mortgage-backed securities. Since banks

were seen as entities which had either stayed out of these markets or

had transferred the risks associated with subprime mortgage loans by

securitizing them and selling them on to others, the banking system,

the core of the financial sector, was seen as relatively free of the

disease.

In practice, however, the exposure of banks to these mortgage-backed

securities and collateralized debt obligations was by no means small.

Because they wanted to partake of the anticipated high returns or because

they were carrying an inventory of such assets that were yet to be marketed,

banks had a significant holding of these assets when the crisis broke.

A number of banks had also set up special purpose vehicles for creating

and distributing such assets which too were holders of what turned out

to be toxic securities. And finally banks had lent to institutions that

had leveraged small volumes of equity to make huge investments in these

kinds of assets. In the event, the banking system was indeed directly

or indirectly exposed to these assets in substantial measure.

It needs noting that even if the exposure of banks to these assets was

a small proportion of the total amount in circulation, the effect of

such assets turning worthless can be debilitating for the banks for

two reasons. First, even if the proportion of derivative assets held

by the banks was small, the value of that exposure tended to be high

because of the large volume of such assets circulating in the system.

Because securitization is geared to transferring risk off the balance

sheet of the originator of the base asset, the tendency in the system

is for the creators of such assets to discount risk and create large

volumes of excessively risky credit assets, as happened in the subprime

mortgage market. The effects of this tendency to sharply increase the

volume of asset-based securities was aggravated by the easy money environment

that was created by the Federal Reserve under Greenspan as part of an

effort to keep a credit-financed boom going in the system.

Second, the equity base of most banks is relatively small even when

they follow Basel norms with regard to capital adequacy. Banks can use

a variety of assets to ensure such adequacy and the required volume

of regulatory capital can be reduced by obtaining assets with high ratings

(which we now know are not an adequate indicator of risk). This results

in the available regulatory capital being small relative to the risky

asset-backed securities held by the banks.

The difficulty with these kinds of bad assets is that they are valued

on marked-to-market principles, implying that since these assets are

not all being traded, there is a lag in the recognition of the losses

suffered through holding such assets. In the US, the process of price

discovery began a long time back when in August 2007 Bear Stearns declared

that investments in one of its hedge funds set up to invest in mortgage

backed securities had lost all its value and those in a second such

fund were valued at nine cents for every dollar of original investment.

What was noteworthy was that Bear Stearns was a highly leveraged institution

holding assets valued at $395.4 billion in November 2007 on an equity

base of just $11.8 billion. Thus it was not just that the assets held

by the bank were bad, but that there were many other institutions, including

banks, that were exposed to bad assets through their relationship with

Stearns. Yet they were slow in recognizing their potential losses.

On March 14, 2008, Bear Stearns was put on life support with what appeared

to be an unlimited loan facility for 28 days delivered through Wall

Street Bank J.P. Morgan Chase. That life support came when it became

clear that, faced with a liquidity crunch, Bear Stearns would have to

unwind its assets by selling them at prices that would imply huge losses.

This would have had spin off effects on other financial firms since

the investment bank had multiple points of interaction with the rest

of the financial community. Besides being a counter party to a range

of transactions that would turn questionable, its efforts to liquidate

its assets would affect other investors holding the same or related

securities and derivatives through a price decline. Fearing that the

ripple effects would lead to a systemic collapse, the Fed, in collaboration

with JP Morgan, sought to prop up the investment bank. The Financial

Times quoted an unnamed official who reportedly declared that Bear Stearns

was too ''interconnected'' to be allowed to fail at a time when financial

markets were extremely fragile.

However, this lesson had not been learnt in full. When in September

last year, troubled Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc., the fourth largest

investment bank on Wall Street came to the table with requests for support,

it was refused the same. The refusal of the state to take over the responsibility

of managing failing firms was supposed to send out a strong message.

Not only was Lehman forced to file for bankruptcy, but a giant like

Merrill Lynch that had also notched up large losses due to sub-prime

related exposures decided that it should sort matters out before there

were no suitors interested in salvaging its position as well. In a surprise

move, Bank of America that was being spoken to as a potential buyer

of Lehman was persuaded to acquire Merrill Lynch instead, bringing down

two of the major independent investment banks on Wall Street.

This was, however, only part of the problem that Lehman left behind.

The other major issue was the impact its bankruptcy would have on its

creditors. Citigroup and Bank of New York Mellon were estimated to have

an exposure to the institution that was placed at upwards of a staggering

$155 billion. A clutch of Japanese banks, led by Aozora Bank, were owed

an amount in excess of a billion. There were European banks that had

significant exposure. And all of these were already faced with strained

balance sheets. Soon trouble broke in banking markets with a spurt of

bank failures seeming inevitable. Though indications of this problem

emerged at least a year-and-a-half ago, what was surprising was that

the full import of the problem at hand was not recognized. In the US,

and elsewhere in the world, the problem confronting the banks was seen

as two-fold: ensuring adequate access to liquidity so that they are

not victims of a run; and, cleaning up their balance sheets by writing

off or getting rid of their bad assets.

In what followed, central banks pumped huge amounts of liquidity into

the system and reduced interest rates. In the US, the Federal Reserve

offered to hold the worthless paper that the banks had accumulated and

provide them credit at low interest rates in return. But the problem

would not go away. By then every institution suspected that every other

institution was insolvent and did not want to risk lending. The money

was there but credit would not flow through the pipe with damaging consequences

for the financial system and for the real economy.

It was at this point that it was realised that what needed to be done

was to clear out the bad assets with the banks. Among the smart ideas

thought up for the purpose was the notion of splitting the system into

‘good' and ‘bad' banks. If a set of bad banks could be set up with public

money, and these banks acquired the bad assets of the banks, the balance

sheets of the latter, it was argued, will be repaired. The bad banks

themselves can serve as asset reconstruction corporations that might

be able to sell off a part of their bad assets as the good banks get

about their business and the economy revives.

This idea missed the whole point, because it did not take account of

the price at which the bad assets were to be acquired. If they were

acquired at par or more, it would amount to blowing taxpayers' money

to save badly behaved bank managers, since the assets were likely to

be worth a fraction of what they were actually bought for. On the other

hand, if some scheme such as a reverse auction (or one in which sellers

bid down prices to entice the buyer to acquire their assets) is used

to dispose of the bad assets, then the prices of these assets would

be extremely low and good banks would incur huge losses which they would

have to write down leading to insolvency. The only way out it appeared

was if these banks just wrote down their assets and were saved from

bankruptcy by the government through recapitalisation or the injection

of equity capital into them. Additional equity injection leading to

nationalization seemed unavoidable. What is more as the dimensions of

the problem needing resolution became clear the extent of the nationalization

required seems substantial.

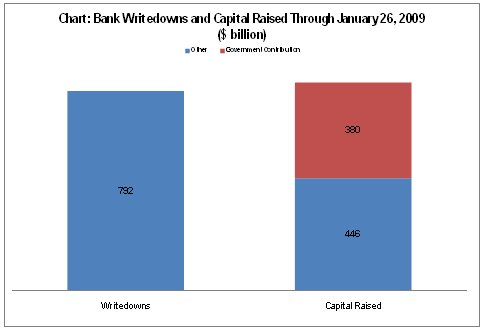

In its update to the Global Financial Stability Report for 2008, issued

on January 28, 2009, the IMF has estimated the losses incurred by US

and European banks from bad assets that originated in the US at $2.2

trillion. Barely 2 months back it had placed the figure at $1.4 trillion.

Loss estimates seem to be galloping and we are still counting. The IMF

estimates that these banks that have already obtained much support including

capital would need further new capital infusions of around half a trillion.

With that much and perhaps more capital going in, public ownership of

banking would be near total in some countries. By late January 2006,

Bloomberg estimates, banks had written down $792 billion in losses and

raised $826 billion in capital, of which $380 billion came from governments.

Though

the problem originated in the US, nationalization occurred first in

Iceland (where the need was immediate), in Ireland starting with Anglo

Irish Bank and expected to be necessary in the case of Bank of Ireland

and Allied Irish Banks and in the UK were Royal Bank of Scotland and

Lloyds Group are now under dominant public control, and others are expected

to follow. However, even here the willingness to declare the process

as nationalization is still lacking. In the US, the government initially

found ways of providing capital but not demanding a say. But this proved

disastrous, since it became clear that old habits of managers used to

being paid to speculate die hard. Huge salaries and bonuses were being

paid out of money meant to save dying banks. So intervention became

necessary and is part of the plank being espoused by President Barack

Obama. Yet, when the threat of inevitable nationalization resulted in

a sharp fall in the share values of the likes of Bank of America and

Citigroup, that are surviving on government money, White House spokesman

Rober Gibbs told reporters that ''The President (Barack Obama) believes

that a privately held banking system regulated by the government'' is

what the US should have.

What is missed is that the inevitability of public ownership that is

now being recognized stems from a deeper source. The problems that drove

the system to inevitable nationalization arose because of the transition

in banking from a structure that was based on a ''buy-and-hold'' strategy

(where credit assets were created and held to maturity) to one that

relied on a ''originate-and-sell'' strategy in which credit risk was

transferred through a layered process of securitisation that created

the so-called toxic assets. The deregulation of banking was crucial

for this transition. It permitted securitisation and also allowed a

geographically extensive banking system to create credit assets far

in excess of what would have been the case in a more regulated system,

so that they could be packaged and sold. The role of banks as mere agents

for generating the credit assets that could be packaged into products

meant that risk was discounted at the point of origination, since banks

felt that they were not holding the risks even while they were earning

commissions and fees. This transition was made possible by the process

of deregulation that began in the 1980s and culminated in the Gramm-Leach-Bliley

Modernization of Act of 1999, which completely dismantled the regulatory

structure and the restrictions on cross-sector activity put in place

by Glass-Steagall in the 1930s.

Why did deregulation occur, when a system regulated by Glass-Steagall

and all it represented served the US well during the Golden Age of high

growth in the US? It did because implicit in the regulatory structure

epitomised by Glass -Steagall was the notion that banks would earn a

relatively small rate of return defined largely by the net interest

margin, or the difference between deposit and lending rates adjusted

for intermediation costs. Thus, in 1986 in the US, the reported return

on assets for all commercial banks with assets of $500 million or more

averaged about 0.7 per cent, with the average even for high-performance

banks amounting to merely 1.4 per cent. This outcome of the regulatory

structure was, however, in conflict with the fact that these banks were

privately owned. What Glass-Steagall was saying was that because the

role of the banks was so important for capitalism they had to be regulated

in a fashion where even though they were privately owned they would

earn less profit than other institutions in the financial sector and

private institutions outside the financial sector. This amounted to

a deep inner contradiction in the system which set up pressures for

deregulation. Those pressure gained strength during the inflationary

years in the 1970s when tight monetary policies pushed up interest rates

elsewhere but not in the banks. The result was a flight of depositors

and a threat to the viability of banking which was used to win the deregulation

that gradually paved the way for the problems of today. What became

clear was that Glass-Steagall type of regulation of a privately owned

banking system was internally contradictory. It would inevitably lead

to deregulation. But as we know now such deregulation seems to inevitably

lead back to nationalisation. So what capitalism needs for its proper

functioning is a publicly owned banking system. That implies that the

current move to ''inevitable'' nationalisation cannot be just ''temporary''

as Greenspan wants it to be.

©

MACROSCAN 2009